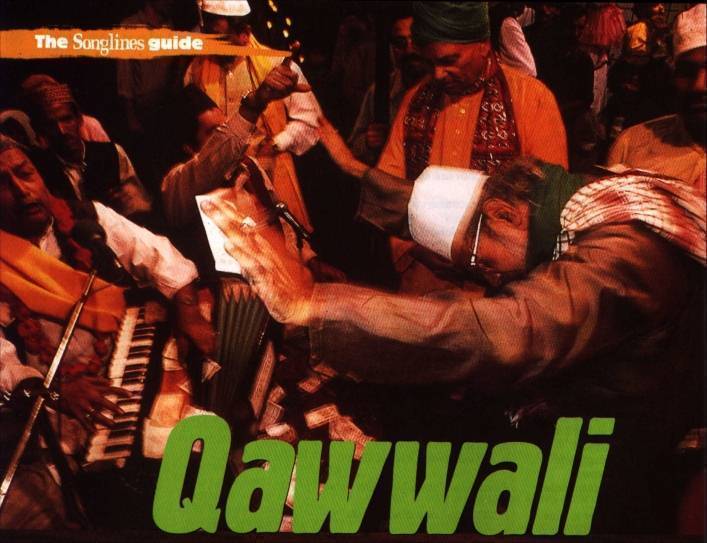

If you're familiar with the voice of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, then chances are you will have heard qawwali, the 700 year old tradiiton to which he belonged. Jameela Siddiqi explores the powerful trance music of the Sufis - or Islamic mystics - of India and Pakistan.

If there is one musical genre from the Indian subcontinent that has outstripped all others in terms of global popularity, it is qawwali - the devotional music of the Sufis, or Islamic mystics, of North India and Pakistan. Pulsating drum rhythms, vigorous hand-clapping and a chorus of male voices entice the uninitiated. At one level, qawwali is simply powerful trance music, but for its followers every experience of listening to qawwali is a renewal of that spiritual feeling which transports them to another plane of consciousness.

The word qawwali derives from the Arabic word qawl, meaning 'utterance' - in this case, of the Divine message. While qawwals - performers of qawwali - used simply to be practioners of a particular kind of devotional music, in the early 1980s they and their musical tradition were discovered by the West notably by Peter Gabriel and his WOMAD festival - and were suddenly catapulted into the 'world music' arena, where their status as musicians has become as important as their role of messengers of God. The lifestyle of a traditional qawwal, who literally sings for his supper at the shrines of Sufi saints and masters, is a far cry from the five-star treatment and lucrative recording contracts enjoyed by qawwali performers in the Western world. But even these professional recording artists, notably the late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, have remained true to the essence of their art, which delivers a message of universal love with an emphasis on the unity of creation - a central Sufi belief in which all people are one and equal, a collective product of a single Creator. Nusrat and others have continued to perform the duty of the qawwal by spreading the message in whichever way is most easily understood by the audience. As Nusrat once explained, "The job of a qawwal is to ensure that his listeners feel closer to the Creator. Qawwali is about reducing the distance between Creator and created." Nusrat in particular made substantial concessions to the tastes of Westerners, consequently reaching a far wider range of people than the early qawwals could ever have imagined possible. Purists have of course been horrified by Nusrat's popularity among clubbers and pop fans, who have enjoyed the use of his voice on pop records accompanied by videos showing scantily clad young women, by his contributions to Western film soundtracks (such as Dead Man Walking of 1996, also featuring Pearl Jam singer Eddie Vedder) and by his own compositions for Bollywood films. But it is thanks mainly to Nusrat's venture into the rest of the world that those outside India and Pakistan have been able to hear real qawwali without having to make a pilgrimage to one of the countries' Sufi shrines.

Music

to feed the soul

Qawwali was created by Amir Khusrau (1253-1325), who was of mixed Indian and

Turko-Persian parentage, under the auspices of his Indian Sufi master Hazrat

Nizamuddin Awliya of Delhi (1242-1325). While Nizamuddin oversaw the development

and perfection of qawwali's classical repertoire, Khusrau, Nizamuddin's favourite

pupil, was the genre's main architect, responsible for the creation of its unique

musical and poetic form. The style of the music itself was directly influenced

by the spiritual practices of the Chishtiya order of Sufis (founded around 1236),

of which Nizamuddin was a 'master'. For the Chishtiyas the role of music is

to raise spiritual awareness and to feed the soul - literally: it is said that

Nizamuddin himself would not eat without first listening to qawwali. Khusrau

wrote many qawwali compositions to please his master, and the master-disciple

relationship is a key theme of qawwali, with many songs dealing exclusively

with the subject of unconditional devotion to 'masters', or spiritual guides,

both past and present. For the Sufi, the spiritual path of love and truth cannot

be traversed without the guiding light of a master.

The music has its roots in the traditions of Iran, though it in no way resembles present-day Iranian music. Instead it shares certain features with North Indian light classical music - the use of ragas (melodies modes) and talas (rhythmic cycles) - but is otherwise characterised by a number of distinctive, unique features. Nizamuddin is believed to have had one specific creative role in the development of the genre: he suggested to Khusrau the use of a chorus. Khusrau had been composing the verses, playing and singing all by himself, so Nizamuddin suggested he form a group.

A qawwali group consists of anything from four to 16 male musicians, usually all part of the same family. The eldest member usually takes the lead vocal part, with a younger brother providing a second, counterpoint voice and the rest of the group joining in at the choruses. The main melody is introduced and frequently restated by the harmonium, a Western import brought by Portuguese missionaries in the sixteenth century which replaced the original sarangi. This upright fiddle is still used to accompany other types of North Indian vocal music but fell out of favour with qawwali musicians because of the amount of time needed to re-tune it between different numbers. Percussion is provided by the tabia drums and, most distinctively, by the clapping of hands in unison, which enhances the rhythm not only by marking time but also by sounding the off-beats. It is this unique percussive quality which distinguishes qawwali from all other kinds of North Indian music.

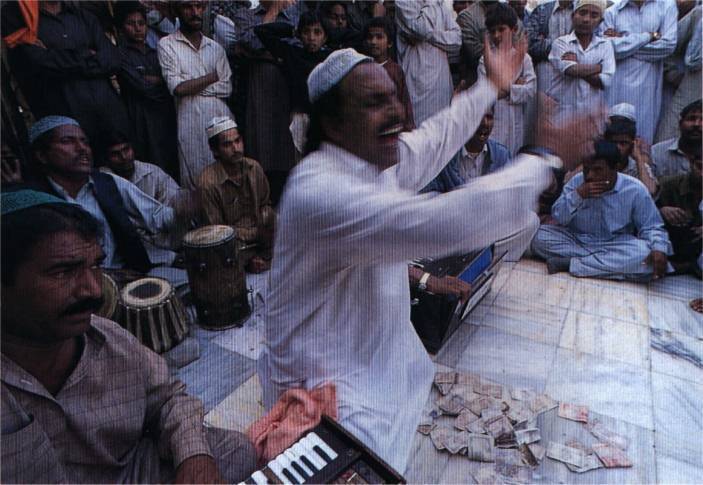

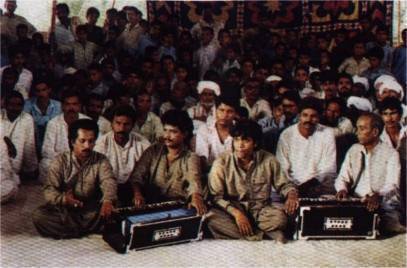

A qawwali gives a passionate

performance at a shrine in Pakpattan, Pakistan. On the floor is a sizeable nazar

(gift of money) from the audience (Photo:Friedrichs)

The structure of a qawwali song is usually based on a single refrain which is continuously repeated until its meaning sinks deep into the listener, becoming clearer with each repetition. In their rapture, enlightened listeners can often be seen to fall into a trance, and sometimes even lose consciousness. When this happens the lead singer takes control and begins to intensify the refrain with each repetition in order to give the listener the opportunity to feel the full impact of the phenomenon. He then gradually lessens the frequency of the repetition, using a specifically prescribed rhythm, until the listener regains consciousness. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was a master of this ability to put listeners into a trance, and although he often appeared to being going into one himself, he always managed to retain complete control over his performances, bringing entranced listeners back to earth gently and seductively. Having fired such a frenzy inside them, he was still able to leave them in a state of calmness, peace and joy.

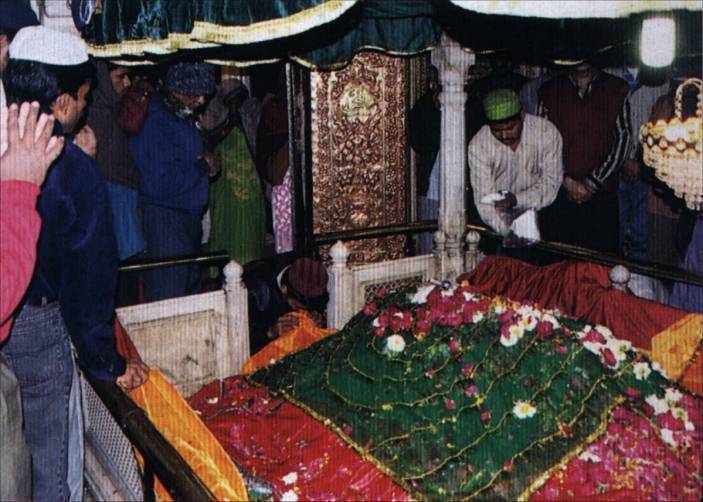

Visitors to the tomb of Sufi

master Hazrat Nizamuddin Awliya in Delhi (Photo:Broughton)

An authentic performance,

or mehfil-e-sam'a ('assembly of listeners'), of qawwali is supervised by a senior

shaikh ('spiritual guide') and may take place either at a shrine of a Sufi master

or at a khanaqah, a Sufi meeting place. While a performance at a shrine is a

public event, a performance at a khanaqah is reserved strictly for initiated

members of a particular Sufi order or for the disciples of the presiding shaikh.

It is by no means a form of entertainment, but a serious, devotional act in

which listeners are expected to arrive in a state of wuzu (ritual ablution)

and be seated according to the instructions of the shaikh. The ideal sitting

position is either to kneel down with the hands joined on the left thigh, or

to sit cross-legged with the feet tucked well under and out of sight; it is

considered the height of rudeness to expose one's feet. Applause is forbidden

at all times; appreciation is shown only by praising Allah ('Subhan Allah')

or by offering the musicians a small amount of money known as the nazar, meaning

'gift'. The nazar is never handed directly to the musicians but must first be

offered, using both hands, to the shaikh, who then gives it to the musicians.

If the shaikh is particularly impressed by the listerner's reaction, he may

merely touch the money and give permission for it to be handed over directly

- mid-performance - to the singers. The modern concert-hall practice of listeners

climbing onto the stage to shower the singers with banknotes is an absurd corruption

of the nazar practice.

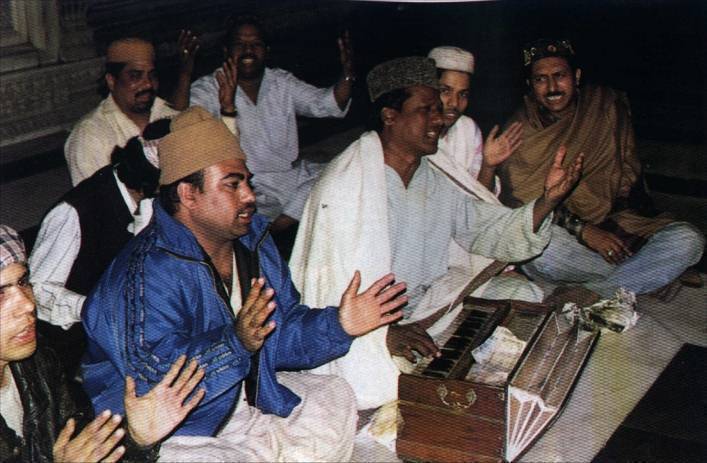

Guardians of the Khusrau

repertoire: the Nizami Brothers and their troupe at the Nizamuddin shrine in

Delhi. Group singing, rhythmic hand-claps and the harmonium are distinctive

features of the qawwali sound. The collection of banknotes is the nazar (gift)

from appreciative listeners (Photo:Broughton)

Old favourites: the songs of father Khusrau

The first qawwals were trained by Khusrau himself. Their descendants, the so-called qawwal bachche (the 'children' of the original qawwals), claim to have preserved the 700-year-old tradition, passing down the music from father to son by a process of oral transmission. The Nizami Brothers are one such group of qawwal bachche. They reside and perform at Nizamuddin's shrine, where they stand guard over a number of rarely-heard compositions from the original Khusrau repertoire and are under instructions from their elders not to sing certain pieces in public, lest these fall victim to the hands of other, more commercially-minded qawwals and become adulterated or corrupted for mass consumption. Consequently, there are almost no recordings available of the Nizami Brothers, although the Auvidis Inedit compilation Musique d'lslam d'Asie includes one track by them.

Khusrau's works still form

the core of the qawwali repertoire performed in Delhi, where performances take

place on Thursday nights (the eve of the Muslim sabbath), or on special anniversaries,

at the shrine of Nizamuddin in the district named after him in the older part

of the city. Khusrau pieces are also performed at the shrines of many other

Sufi masters throughout India and in Pakistan, where the music was transported

with migrating Delhi qawwals after the partition of India in 1947. It can be

difficult, though, to isolate original Khusrau material from later, inauthentic

additions unless you are an expert in either Farsi (Persian) or Braj Bhasha

(also known as 'Old Hindi'), the original languages of qawwali. Qawwals sometimes

claim to be performing a rare work of Khusrau's which they say is known only

to them, but the quality of their texts in the original languages usually reveals

the truth. Navras Records have produced a superb four-disc set of Khusrau songs,

Traditional Sufi Qawwal is, performed by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, which is ideal

for anyone who wants all their Khusrau songs in one place. Although the recording

was made in London just 11 years ago, it contains the spiritual atmosphere of

a medieval Thursday night at Nizamuddin's shrine. The album is one of the best

collections of qawwali available, both in terms of content and the authentic

spirit of the performance.

The Sabri Brothers before

the death of the eldest brother, Haji Ghulam Farid Sabri (with raised arm),

in 1994. As a trio they played a vital role in preserving and spreading the

Khusrau repertoire (Photo:Drake)

Pakistan's three Sabri Brothers also played a vital part in preserving and spreading the original Khusrau repertoire, and can arguably take even more credit than Nusrat for popularising these songs outside the subcontinent. For while Nusrat was still concentrating on the Punjabi Sufi repertoire, most of the Sabris' performances featured works by Khusrau, and it was the suprising popularity of these classical Khusrau songs in the West which encouraged Nusrat to return to the repertoire - with great success. The Sabris recorded some memorable Khusrau items, as well as one of the finest performances of songs to the texts of the Persian Sufi poetJami (1414-1492), on Piranha Records. The song that became their signature tune was the traditional Sindhi folk-tune 'Mast Qallandar', sung in praise of Usman Marwandi, a mysterious thirteenth-century Sufi saint more popularly known as Lal Shahbaz Qallandar. This hypnotic song, which is set to the rhythm of the dhamal trance dance, is still performed after the main evening prayer at the shrine of Qallandar in the Sindh province, but the Sabris often used to sing it in preference to the traditional 'Rang' of Khusrau to round off their concert performances of qawwali.

When the eldest Sabri brother, Haji Ghulam Farid Sabri, died suddenly in 1994, the remaining duo began to move away from the Delhi tradition, preferring instead to follow the current Pakistani fashion for singing modern Urdu ghazals (light classical songs) set to Middle Eastern pop melodies and peppered with phrases in Arabic, though it is interesting that now Nusrat is no longer alive, they seem to be returning to the Khusrau repertoire.

Folk qawwali: the Punjabi and Sindhi traditions

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was descended from a distinguished musical family of the Punjab, and as well as singing the Khusrau repertoire of Delhi, he was also one of the finest exponents of the songs of various Punjabi Sufi saints, notably Baba Bulleh Shah (1680- 1753). Nusrat's finest performances of this repertoire were captured by the Ocora label in a box-set which also features some of the best compositions written by members of his own family, notably those in praise of Hazrat Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammed and the figure revered by all Sufis as the embodiment of the perfect being. The best known of these songs, which are collectively known as Manaqibat-e-Ali ('In Praise of All'), is 'Ali, Ali, Ali Maula All Ali Haq'. The song, which is included on the Ocora set, is structured so that the word haq, meaning 'truth', is placed at a point when the singer can take quick breath, in keeping with the Sufi practice of zikr, or 'rememberance', which is based on certain breathing techniques.

Bakhshi Javed Salamat Qawwali:

performers of folk-style Punjabi qawwali (Photo:Anon/Vivier)

The adjacent provinces of Punjab and Sindh (both now part of Pakistan) share a cultural, linguistic, musical and spiritual tradition distinctive from that of Delhi, and are also themselves treasure troves of Sufi music. Sindh has more Sufi shrines than almost any other part of the world, the most important being the shrine of Shah Abdul Latif (d.1752). One of the finest recent recordings of qawwali from Punjab and Sindh is the two-disc album Troubadours of Allah on Wergo, which features a variety of artists from both provinces and is an absolute must-have for all enthusiasts of Sufi music. Shanachie's Land of the Sufis, Wergo's Pakistani Soul Music and Network's Sindhi Soul Session also provide valuable insight into the Sufi tradition of Sindh, and Arion's Musique du Penjab, Volume 3 is also a good sampler. Although closely related to the 'classical' Delhi style in terms of its spiritual impact, the regional - or folk - style of qawwali from Punjab and Sindh is a musical form in its own right, being more closely related to Punjabi folk music than to North Indian classical forms. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan himself felt that the Punjabi language had a directness and frankness of expression that readily lent itself to the simple Sufi message of loving kindness. The Real World label features some of Nusrat's most flawless Punjabi performances from his early, energetic days, notably Shahen-Shah and the outstanding Mustt Mustt. However, only two of the 11 tracks on this latter album have texts. In the rest of the songs, words are used not so much for their meaning but for the way they actually sound, underlining Nusrat's belief that music is itself a language. Produced by Michael Brook, the album includes everything from guitars and synthesizers to Cuban bongo drums and piano, and the result is a lavish feast for the ears. Die-hard purists will lament the total absence of the shrine atmosphere, but Brook had embarked specifically on a musical experiment and the result is one which Nusrat himself found very satisfying.

Following Nusrat's death, themost electrifying performances and recordings of qawwali have come from his nephews Rizwan and Muazzam, who have revived the original languages of qawwali, Farsi and Braj Bhasha. In addition, their youthful exuberance and energy add a dimension to the music which is more than just a little reminiscent of Nusrat before his health started to fail him. They have two excellent recordings on Real World, Sacrifice to Love and Attish: The Hidden Fire.

Mixed blessings: qawwali and the West

It is perhaps ironic that the best recordings of qawwali have come from record labels based outside the subcontinent. While Pakistani labels (such as EMI) have released myriad cassettes of qawwali, albeit of the more popular modern Urdu and Punjabi kind currently popular in Pakistan, Indian companies have made little of the opportunities given to them by having the greatest Sufi shrines - those of Nizumuddin and founding Sufi master Khwaja Mohinuddin Chishti - on their doorstep. With qawwali sung every Thursday night and on numerous special occasions (such as the anniversary of the death of a Sufi master), a live recording of such events would not be difficult to arrange. None the less it is usually French, German or Japanese labels who arrive with their recording equipment. Perhaps one reason for the lack of Indian recordings is that although Indians have a long and thriving recording tradition, they have never considered qawwalias a commodity. In India it has always been considered out of bounds of commercial enterprise and instead remains within the sacred confines of Islamic religious practice and ritual. Back in the 1960s, for example, the few recordings that existed were private ones made during commissioned recitals at the houses of discerning listeners. Nobody would have imagined that qawwali would become one of the most popular 'world music' genres and that its popularity outside India would far exceed that of film music. In his book Indian Music and the West (Oxford University Press. 1999). Gerry FarrelI sharply observes the irony of qawwali popularity in the West at a time when Islam is being demonised by Western media. Generally unable to understand the messages contained in the words. Western audiences have reacted mainly to the music's intoxicating rhythms. There could be no clearer example of an essentially Islamic practice being revered outside its own context.

The growing global enthusiasm for qawwali is however, double-edged. The same fervour which led to its dissemination has also led to its dilution. Linguistic and cultural barriers have been blurred for the sake of popularisation and performance contexts changed, as dictated by modern concert-hall arrangements and sanitised recording studios where performances take place against stoney silence. Indeed, a qawwalw^o sits high up on a concert stage is already breaking the first rule of a Sufi musician, according to which a truly great qawwal is one who seems absent from his own peformances. For in the moment of evoking God's name he is not supposed to exist but simply to act as a channel through which the Divine message of love. conveyed in music and poetry, merely passes through him to the hearts of listeners. 0

Some

Quintessential Qawwali recordings |

|

|

Bakhshi

Javed Salamat Qawwali Musiques du Pendjab, Volume 3 (Arion ARN64323) |

| Nusrat

Fateh Ali Khan Live in London: Traditional Sufi Qawwalis (Navias NRCD0016/17/28/29 - four discs, only available separately) |

|

|

Nusrat

Fateh Ali Khan Mustt Mustt (Realworld CDRW15) |

|

Nusrat

Fateh Ali Khan Shahen-Shah (Realworld RWCD3) |

|

Nusrat

Fateh Ali Khan Back to Qawwali/Nusrat Forever (Long Distance 122083 - long double CD box set) |

|

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan En concert a Paris (Ocora C570500 - five discs also available separately) |

|

Rizwan-Muazzam

Qawwali Sacrifice to Love (Realworld CDRW79) |

|

Rizwan-Muazzam

Qawwali Attish: The Hidden Fire (Realworld WSCD201) |

|

The

Sabri Brothers Jami (Piranha CDPIR1039) |

|

Various

artists Land of the Sufis: Soul Music from the Indus Valley (Shanac'hie 66017) |

| Various

artists Musique de 1'islam d'Asie (Auvidis Inedit W260022) |

|

|

Various artists - Pakistani Soul Music (Wergo SM1529) |

|

Various

artists Sindhi Soul Session (Network 32.378) |

|

Various

artists Troubadors of Allah - Sufi Music from the Indus Valley (Wergo SM 1617 - two discs) |