Massive Attack talk paranoia, fear, big brother and fine wines in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius.

It wasn't meant to be like this...

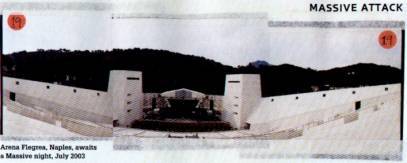

Dawn breaks early over the only half-decent bit of beach in the bay of Naples, and a significant minority of the 40-odd folk that make up the Massive Attack touring party are wondering how to get home. For the past six hours they have drunk, smoked and generally enjoyed themselves like there was no tomorrow. Then tomorrow became today, and today, in touring parlance, is a "show day". Before the sun sets again they will deliver to 6,000 Italian fans a faultless gig that bears no traces of its performers' nocturnal exertions. Then it's back to the beach, more of them this time, to pick up where they left off - not that things had ever really stopped. No, it wasn't meant to be this way at all.

The current, if superficial, media consensus is that Massive Attack are a band who release progressively "darker" albums, who take an active political stance in an increasingly apathetic art form and operate somehow amidst an internal atmosphere of creeping paranoia and internecine rivalry.

A climate not helped, one imagines, by the recent completely disproved but nonetheless very public accusations linking Robert "3D" Del Naja - at times the band's only member in the traditional sense of the word - to the police's vast internet paedophile swoop, Operation Ore.

I had no more expected to find them living it up on beaches at daybreak than I would have expected to have found them riding unicycles and singing "Eye Of The Tiger". Which goes to show how wrong you can be. The "good times" ethos that sustains Massive Attack on the road (if not always on record) is unsurprising if you consider their origins.

To think of them as a band is to misunderstand their evolution since their earliest days as a Bristol sound system at the end of the Eighties. Today Del Naja is quite happy to refer to them as "more of an idea than a band", but whatever the components and people that form that notion, something of the original "play some records, sell some beer and get down" ethic abides. The surprise is that it has survived so many changes in personnel and such extremes of circumstance.

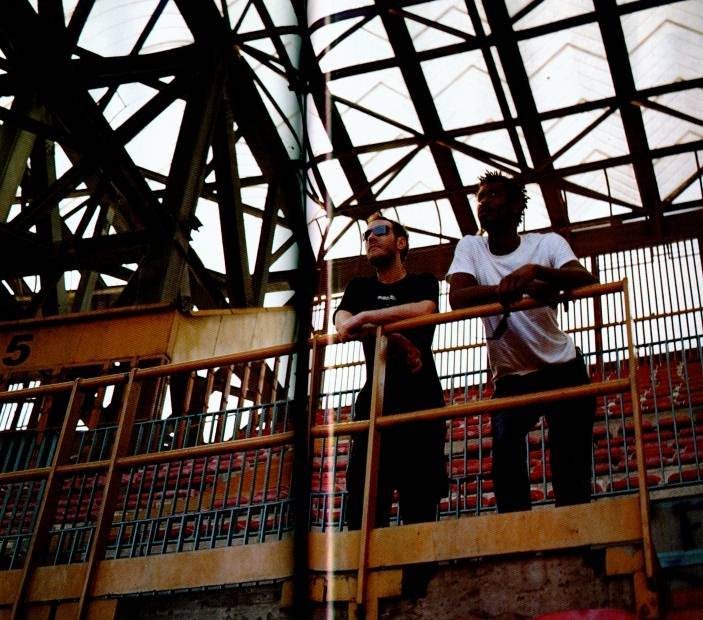

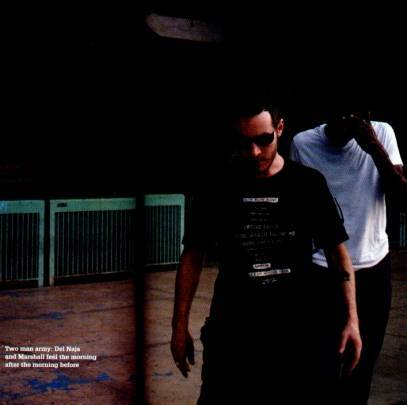

Del Naja, the one constant at the heart of the collective, is an unlikely pop star. He is short, edgy, manic, slightly feral round the edges but fundamentally energetic and commendably pale for someone who has been touring places far warmer than Britain for six months. You wouldn't recognize him. This is probably a conscious thing. By his own admission he has sought to prevent his own image obscuring the considered presentation of the band, the sleeves and videos for which he also takes responsibility.

Visually, the difference between him and Grant "Daddy G" Marshall is almost comic. Grant is at least six foot five, relaxed, and immaculate, a man who, though by no means withdrawn, you suspect receives far more than he transmits. Legend has it that relations between the two were such that on completion of the latest album, 100th Window (on which Robert was the only original member involved) Grant, taking a sabbatical, signalled his absent approval of the record to his old friend only via text message.

Under the shadow of Vesuvius on a burning blue afternoon, such tensions are

clearly forgotten. Grant is back on tour "because I missed it really, I

missed the studio, the whole thing". An outfit that has sustained the arrival

and departure of such diverse talents and personalities as Tricky, Nellee Hooper,

Andrew "Mushroom" Vowles, Shara Nelson et al is clearly more elastic

than most. The door swings both ways. On the afternoon after the pre-show party

that was the night before, the two of them seem very much at ease. Remarkably

so, even.

"Apart from that recent

history of me and G, the whole point of the band has always been to have fun,"

says Robert, at a pace that belies the West Country accent that drenches his

vowels. "It goes back to when we started with sound systems that didn't

really make any money. We would pay for the generator, the PA. I'd do the artwork

then go to the copy shop, cut and crop all the flyers myself, buy beer from

a wholesaler and sell 'em out the back of a car. It was a really good crack.

"The only reason we

went into the studio in the first place was to make dub plates, to do what the

reggae sound systems were doing and put our own backing tracks together. That

was the only reason we entered a professional environment. There was never any

ambition or desire for fame and fortune, it was something that happened alongside

it.

"Even though your priorities

change - you get older, money does become an issue - the desire to have a laugh

and make music in the way we always have done is still there, I think. It's

always experimental, it's always open-ended. We did parties and gigs and had

problems and disappointments, and it's the same in the studio. There's days

and weeks when things don't work out, and that can be really upsetting. The

whole point is to have a creative outlet and if it isn't doing that then you

feel stifled and frustrated, obviously. But it's all about fun, and the tour

continues that. And I think the same in the studio. It's always been non-egocentric.

The most personality battles are between me and G, but we've known each other

17 years."

Lest we forget, selling beer

from the back of a car and all the rest of it led to the release of Blue Lines.

An album which, along with Soul n Soul's Club Classics, The Stone Roses' debut

and Primal Scream's Scieamadelica defined a unique, remarkable era in British

music, and continues to inform and influence music to this day.

Subsequent releases have

been taken to heart by the mainstream (in particular those in search of backing

music for television, "mainly programmes on serial killers," says

Robert) to the extent that it's possible to misjudge Massive Attack today as

one of those bands that are simply there. In truth they have always been coming

from their own angle, and that is their real consistency.

"I think we always did

that," says Robert. "Every time we brought out a record it was the

exact opposite of what everyone else was doing. When we brought out Blue Lines

everyone was raving. The same during Protection. When Mezzanine came out everyone

in Bristol was doing drum 'n' bass."

Did you set out to do that?

"It's not strategic, we've always done what we want to do. I think all

musicians are self-indulgent."

"So you'll admit that

you're self-indulgent!" says Grant, as if to resume some age old dispute.

At which Robert cracks what's best described as an amiable "fuck you"

smile.

"It's always been a

bit subversive, what we do, in our minds," adds Grant. '"Cos we live

in our own world."

In February of this year,

Massive Attack's own worldfaced its sternest test yet. Along with 7,300 others,

Del Naja's (who at that time was Massive Attack) name was passed to the British

police by American authorities for investigation as part of the aforementioned

Operation Ore. Confident of his innocence, he handed his computer equipment

over to the police. Then in a move that, though illegal, is increasingly commonplace,

someone in the police informed the media, in this case the Sun. Never one to

be thwarted in her quest for arbitrary justice, the paper's editor Rebekah Wade

named him in the paper.

Already "the most paranoid and conspiracy-minded person I know", Del

Naja thus embarked on what he has since referred to as "the worst period

of my life". 100th Window is an album rife with references to surveillance

and the curtailment of liberties.

"Suddenly it seemed like a self-fulfilling prophecy," he says.

Having toyed with disappearing

f' view, he chose to carry on in spite the allegations and commenced the tour.

By the end of March his equipment was returned, the police admitting there was

no evidence of any kind. The likely explanation is that he was unfortunate enough

to have visited a site owned by a company that also owned illegal ones. But

the damage gets done.

He has said since that, "when I leave the house I feel as though there's

a huge arrow over my head.. now I walk into a shop or pub and I can't really

be myself. I have to look everyone twice in the eye." It is an experience

few could walk away from unscathed, if at all. Understandably is not one that,

now that it is behinc;him, he is eager to discuss. When the subject does arise,

I venture in sympathy that, like Lee Harvey Oswald, he has been a victim of

someone else's darker schemes.

"Wait, wait, wait a

second," says Grant, all serious, "you're saying the Oswald didn't

kill Kennedy?" and they both start laughing. Clearly the Massive Attack

world, though rattled maintains its orbit.

"If someone had told

me at the start of the year what was gonna happen..." says Robert...

"...You'd have said

they were having a laugh," ventures Grant.

"I'd have told 'em to

fuck off," concludes Robert.

As the conversation moves

on, Del Naja, who has emerged from his recent history with instincts for enjoying

life enhanced, if anything, makes repeated references to his own cynicism. I

argue that this cannot be absolutely true - if one were truly cynical, why bother

making music in the first place? At its heart, one imagines, it is essentially

an optimistic activity, no matter what its ultimate tone.

"It's twofold,"

he says. "I was thinking yesterday about starting new stuff in the studio

and making lists in my head, and all those things are exciting and positive.

I'm looking forward to it, so it has an optimistic viewpoint entirely. But I

think that's countered entirely by things like, I did an interview with this

guy and he said, 'Is your music getting darker?' I said that's such an overused

word, what does it really mean?

"My point was that the

world in general is

getting darker. With the amount of surveillance we're under, the new American

corporate century we're about to enter, it's a very frightening place. Media

organisations are allowed to monopolise, they can own newspapers, radio and

TV stations and all have political interests. It's dangerous especially if you're

trying to put something out that's not just a hair product, a T-shirt or a chocolate

bar, you're trying to do something creative.

"And that goes for writers,

musicians, artists, film-makers... it's gonna get much, much harder. The whole

idea of our music getting darker is ridiculous. The issue is the media in general.

The media's selling you a lifestyle, when the world is in a precarious position.

Obviously, the idea of selling a lifestyle only works if you can sell a happy,

healthy lifestyle and to do that you have to pretty much ignore what's going

on.

"If you wanna sell this season's look, these sunglasses," indicating

items on the table, "that food, that wine, that product, it has to be sold

in a certain way that leaves no room for anyone to be honest."

Does the mixed reception

of 100th Window reflect that?

"Of course, 'cos people

don't wanna deal with that sort of reality. And with us putting a record out

which is very much reflective of life, of how the people in the W organization

were feeling, it's not a very cool place to put music out at the moment. I think

other bands will continue to suffer from that."

You could, I venture, argue

much of the British media exists in a climate of near oppressive, jollification,

as if to offset reality.

"Democracy doesn't have

to be sold as capitalism," he says. "I think in Britain we're losing

that edge. There's far more awareness and protest here in Europe. It's like

hip hop, when it came out I loved it! It was what punk was, the idea that it

came from a community who had to fight for their survival. Now they've been

absorbed by an industry that uses it every time you see an ad on TV and every

hip hop video and song is selling lifestyle and product. It's selling the American

dream, more so than country and western music."

It all rings true, but surely

here in the sunshine by the sea, entrenched in fine wine and good food we can

take this conversation to a more positive conclusion?

"Naples is a very superstitious

place," says Del Naja, whose family hail from hereabouts. "Southern

Italians are very warm, honest people, they distrust the north, the industrialists.

And living in the shadow of Vesuvius, the fact it could erupt any second while

people seem to build higher and higher up the mountain, they also have this

attitude to life that's 'enjoy it while it lasts'. If it erupts, so be it. Enjoy

what you've got.

"They're not afraid of celebrating life and death and acknowledging it,

like we are in Britain. Where again, in order to

Democracy doesn't have to

be sold as capitalism"

subscribe to this happy lifestyle

you can't really deal with death. Death is old people's homes and funeral parlours,

wills and testaments. You can't celebrate it, you can't acknowledge it. Whereas

in Italy it's the opposite. It's not tribal, but there's more honour and love

and dignity with regard to getting old. It's a more honest way of living."

That evening, Massive Attack's schism between consciousness and celebration

is demonstrated to sublime effect in a gig that combines both elements to near

perfection. The songs (in which Grant and Robert are abetted by Horace Andy,

Dot Allison and a host of lesser-known but equally accomplished performers),

which range in scope from "Unfinished Sympathy" to the less familiar

territory of 100th Window, are backed by a visual display that almost defies

description.

A huge video screen delivers a living light show of constantly regenerating

text in the local language. News updates scroll to the beat, political headlines

swirl and diffuse, weather forecasts are graphically equalised, all in real

time. The effect (one imagines) is something like smoking DMT and watching Ceefax.

Unpleasant though that may sound, it's a stunning accompaniment to the music,

which lifts the whole enterprise to another level. Later still, back on the

beach at dawn again Del Naja sits on a deck chair and laughs.

"Missed yer fuckin' cab home now, aintcha?"

Indeed, but as we now know, there are many worse places to be stuck than under

the volcano.

Story by Michael Holden

Photography by Warren Du Preez and Nick Thornton Jones