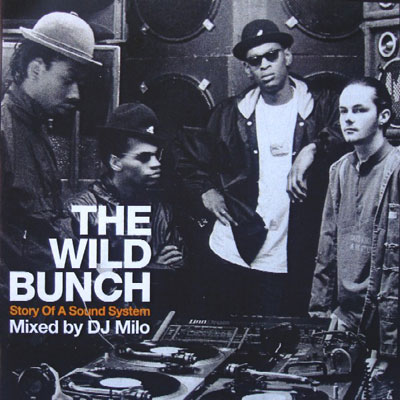

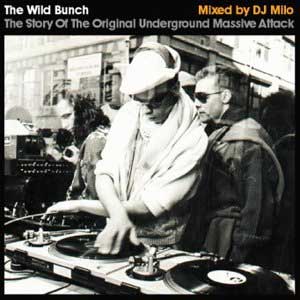

- The Wild Bunch

- The Dug Out

- Nelle

- Milo

- Daddy G

- Willie Wee

- 3D

- Mushroom

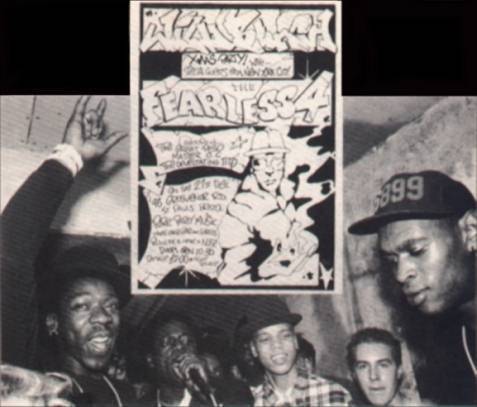

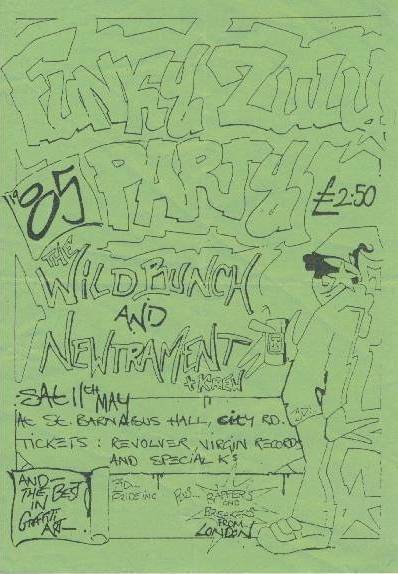

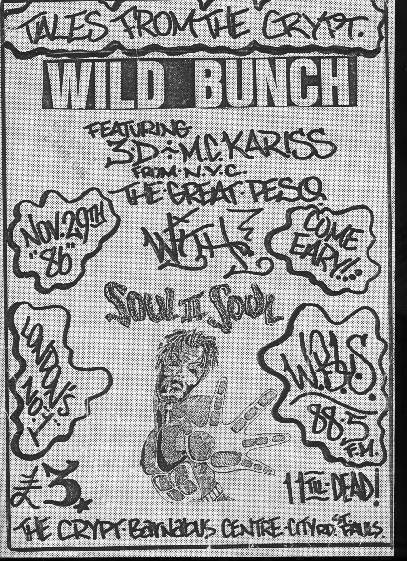

- Flyers

- Tunes

|

House parties, Hip Hop and smoking Drugs....

Massive Attack's history goes back to 1983 and the Wild Bunch. The Wild Bunch

were mid-'80s reggae, hip-hop and soul sound systemeers, who mutated into Massive

Attack. They formed

around the scene that had developed at the Dug Out in 1982 or and comprised Miles Johnson, Nellee Hooper, Grant Marshall (Daddy G), Claude Williams

(Wille Wee), Robert

Del Naja (3D) (who

joined later), and later still, Andrew Vowles (Mushroom). They

were essentially an even looser collective than Massive Attack, and encluded

anyone else who could be trusted to distribute flyers or sell a few cans of

lager. One of the earliest and most

successful sound system/DJ collectives in the UK, they rapidly made themselves

a reputation for their mixing-up of styles and for their sound system parties,

which became so unmissable that the posse was accused of wrecking the local

live-music scene by stealing the audiences.

The Redhouse Jam

"Basically

it was a reggae sound system," recalls Mushroom. "Everyone round the turntables,

just taking turns on the mike." They

started to DJ at the Dug Out, where Marshall was already established, every

Wednesday, and became Bristol's first New York-style sound-system crew. Their

performances at illegal parties, such as on the downs, where the police arrived

to close them down, in 'abandoned warehouses like the Red House in St Paul's.

at private parties, proper gigs like the Granary, or at St Paul's carnival -

where they played till dawn - soon made them a legendary fixture of the Bristol

scene, attracting a loyal following that mixed black hip-hop heads from St Paul's

with Clifton trendies. The

Wild Bunch would epitomise the sound (agglomation of hip-hop, rare groove, soul,

reggae and rock influences) and organisation (loose affiliations of multi-media

artists) of music groups in post hip-hop britain despit only releasing one single

during their five year lifespan. They are largely myth and legend to those who

lived outside Bristol.

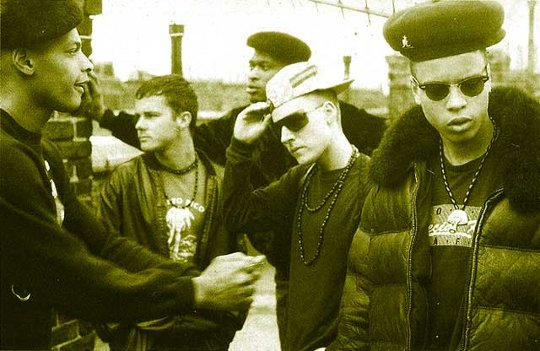

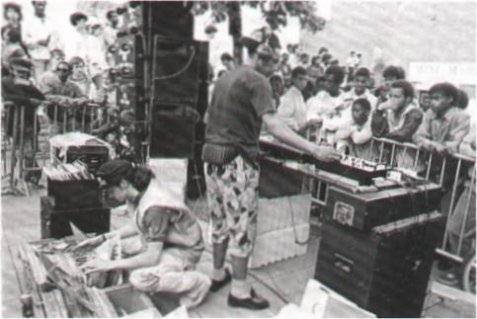

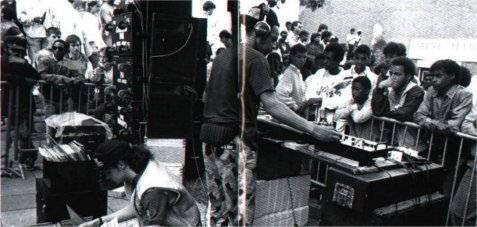

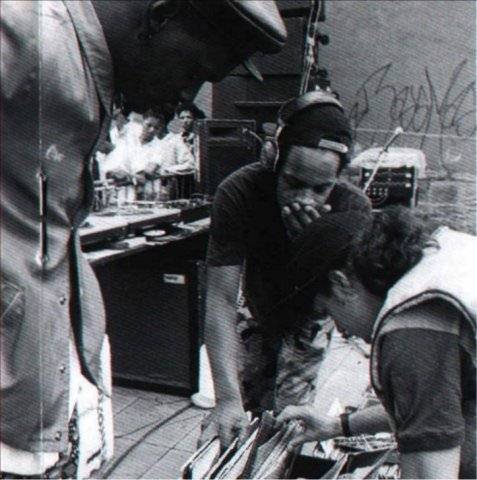

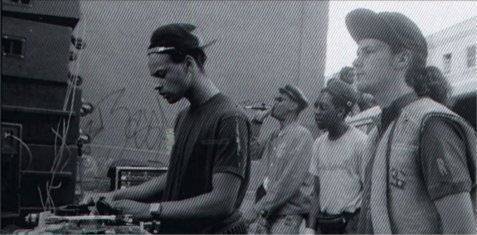

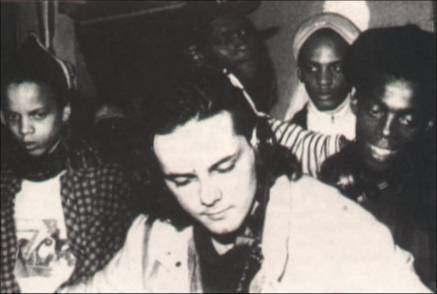

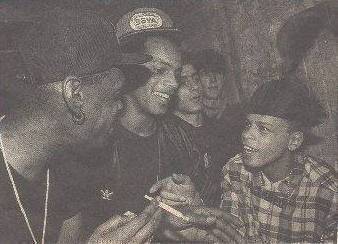

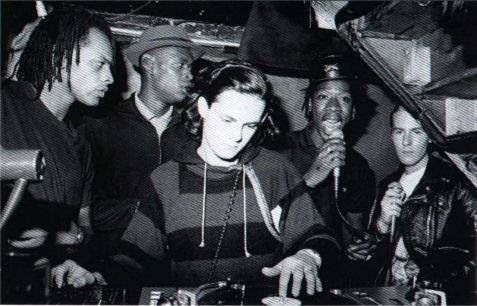

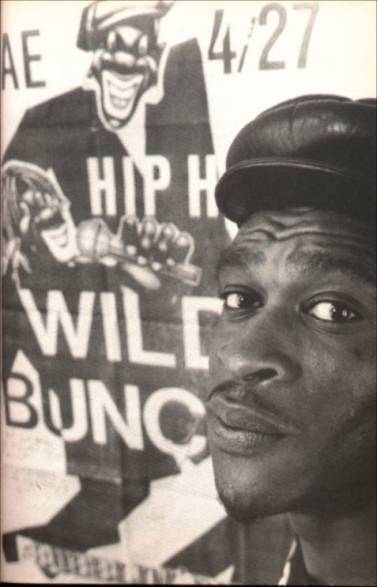

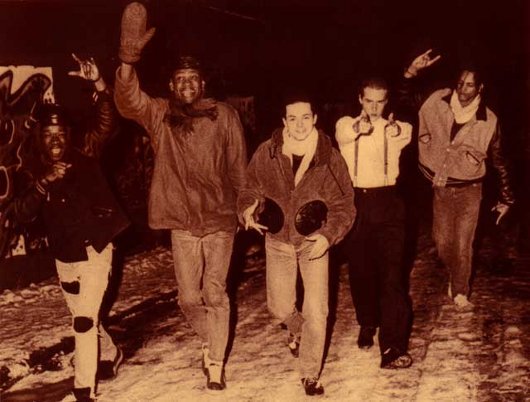

The Wild Bunch at St Pauls Carnival, Bristol, 1985

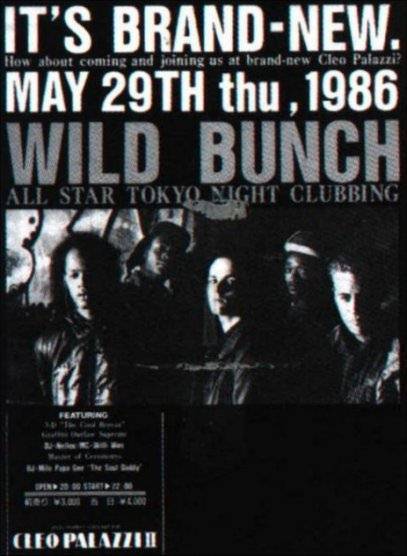

By the

mid-'80s The Wild Bunch and their all-night party jams had gained a reputation

that stretched far beyond Bristol's city limits. In fact, it was a trip to Japan,

of all places, that was the catalyst for the Bunch's demise. 3D got homesick

and came back to Bristol early, while Nelle Hooper left soon afterwards to pursue

his producing interests. He moved to London, to work on the ground-breaking

album that would take the soundsystem Soul II Soul into the pop mainstream,

and produce records for the likes of Bjork and Madonna. "The final straw was

at the St Pauls Festival," explains 3D. "The truck turned up from London with

the sound system, took one look at us, went off for a cup of tea and never came

back.

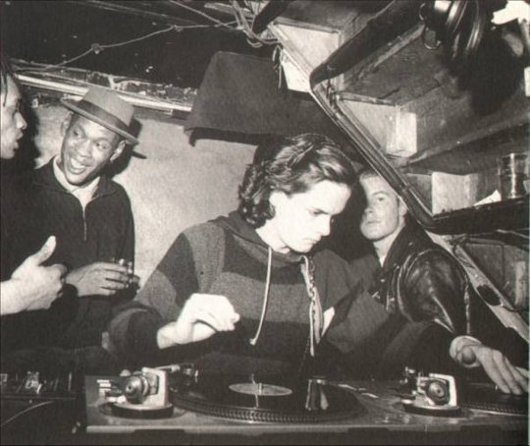

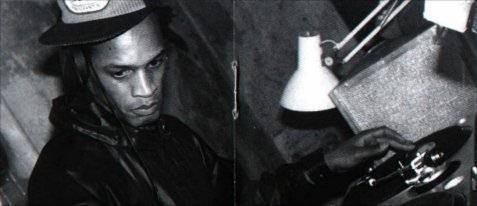

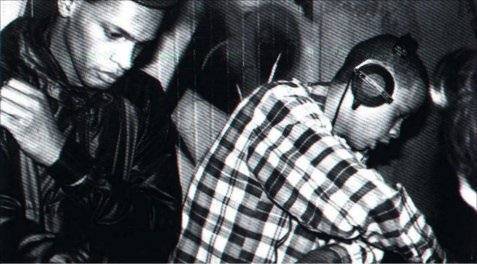

The excellent photographs

that were taken at the time, by Beezer, Julian Monaghan and Rob Scott, who memorialized

the whole period very effectively, show the group posing behind the decks at

the Dug Out. Nellee Hooper looks impossibly young and baby-faced, Grant looks

pretty much as he does now; Del Naja stares out of the frame like the precocious

youth he was, trying to look as hard as his namesake Robert De Niro, and Miles

Johnson - well, he looks like a star. 'I used to fancy him when he was younger',

remembers Sapphire, 'and that's why I used to follow the Wild Bunch around.

But I frightened him once, when I got this pretty girl at the Dug Out to chat

him up. with an eye to coming back to my place for a threesome. He came back

but when he found out what was involved he didn't want to know.'

Hooper and Johnson manned the decks, specializing in grandiose scratching of

early hip-hop records such as those on the Def Jam label, with Marshall also

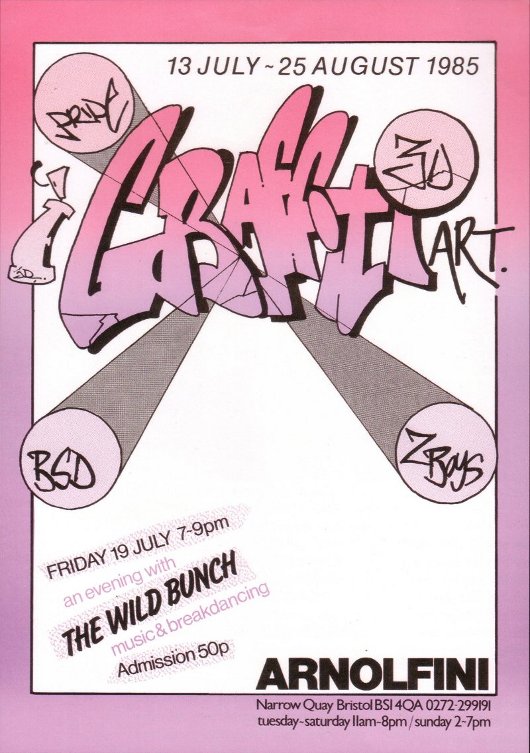

DJing and acting as MC, and Del Naja and Williams rapping. Del Naja was also

a noted local graffiti artist, with several very public and illegally-decorated

sites to his name. some dedicated to the Wild Bunch, and the group thus represented

not only a form of music but an offshoot of the whole, integrated street culture

of the new hip-hop movement, appropriating whatever they could learn about their

New York predecessors into a set of attitudes and practices that were then trans-

planted to their home city.

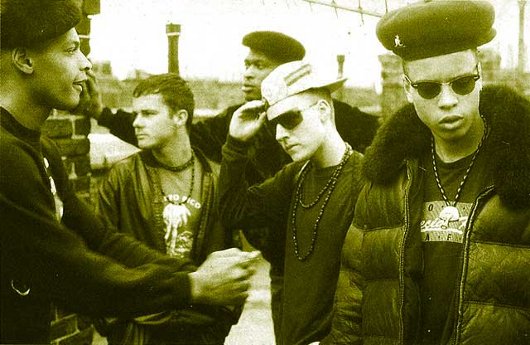

The

Great Peso guesting @ a Wild Bunch jam.

They were also very

disorganized and argued between themselves constantly. In 1985, it was evident

that there was a constant conflict. Del Naja was full of ideas but didn't have

the necessary seniority to communicate them successfully to the others, and

there was a continual air of tension. By this time they were also successfully

on the blag. Del Naja appearing in a documentary about graffiti art being made

by the director Dick Jewell for Channel Four, and getting his graffiti into

a book by author Henry Chalfont, along with Goldie from Wolverhampton.

What happened between

then, and the foundation of; Massive Attack in 1988, is hard to relate without

considering the different versions of the story told by the participants themselves,

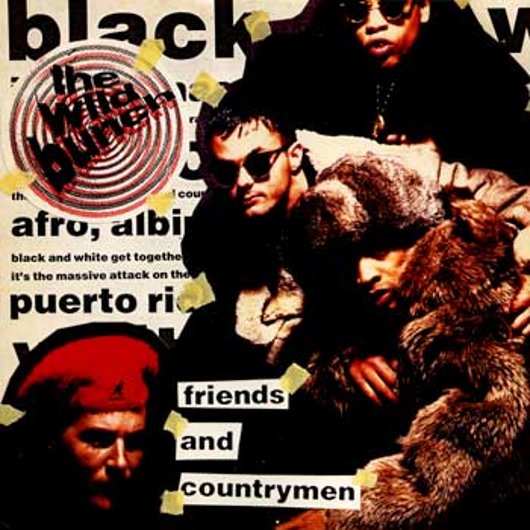

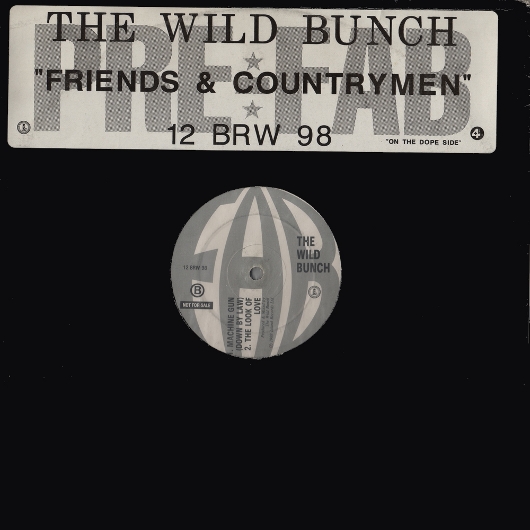

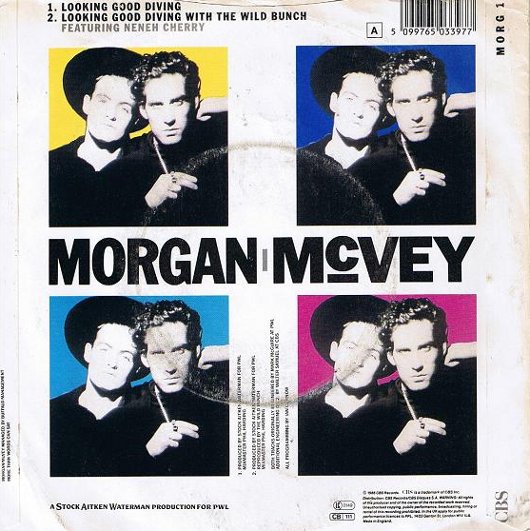

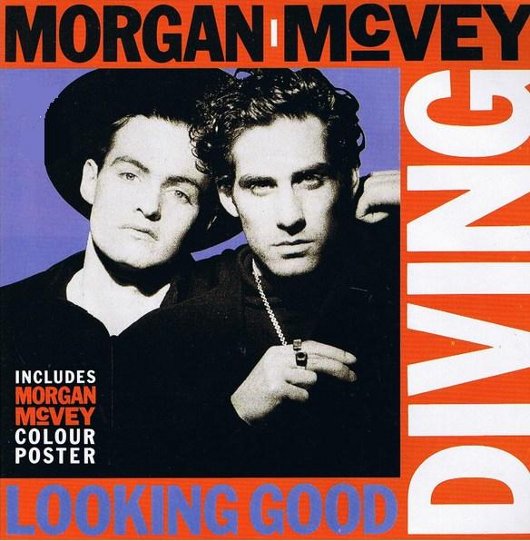

as they diverge on a number of points. The essential facts are that in 1987

the Wild Bunch blagged a trip to Japan through contacts made via Neneh Cherry

and The Face magazine. Del Naja was unhappy there and returned home, ending

up being thrown out of the group. Johnson and Hooper then signed a deal as the

Wild Bunch with Island records, with themselves as the only signatories, and

recorded a couple of singles, including The Look of Love and Friends and Countrymen,

which were released by Island in America and on import in Britain. Johnson and

Hooper, who were by living in London, then fell out and Hooper went To form

Soul to Soul with Jazzie B, while Johnson went to Japan and then to New York.

Del Naja, Marshall & Vowles formed Massive Attack, conceived of as a Soul

II Soul-type project and first mooted as an actual offshot to be produced by

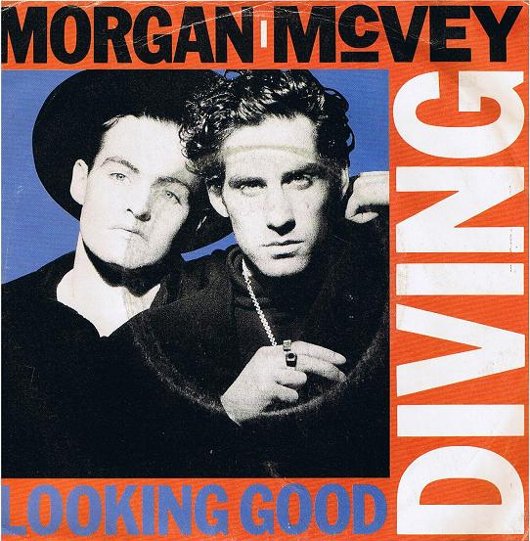

Hooper. Signed to a management by Cameron McVey, Massive then signed a record

contract with Virgin which eventually resulted in Blue Lines album. From

1989 they began fusing together the hip hop, sweet lover's rock reggae, booming

dub basslines and quirky indie pop they'd all grown up with into a new, distinctively

British sound. Developing a sound that took advantage

of the soul/punk/reggae cross-fertilization seen in the early 80s, the hardcore

trio of Delj, Grant and Mushroom decided to move on from playing records to

making them, and Massive Attack was born. Ditching the spraycans and packing

in the breakdancing proved to be an excellent career move.

The Face Magazine

The Face Magazine

The

Dug Out is

remembered fondly by everyone who went there. Bristol didn't have a wide open

nightlife culture to rival New Orleans or Kansas City, it did have one club, the

Dug Out, where black and white mixed fairly freely, unusual in a city centre where

straight clubs like Romeo and Juliets used to operate an unofficial quota system

in allowing entry to black men. And whatever the theory, the Dug Out really does

play a big part in the story. It also links together the mini-boom that Bristol's

musical culture did experience, in the post-punk bohemian fringe of the Pop Group,

Pigbag and Rip Rig and Panic in the early eighties, with the sound-system crew

that went on to become the basis of the Bristol sound, the legendary Wild Bunch. The Wild Bunch formed

around the scene that had developed at the Dug Out in 1982 or so. They then started

to DJ at the Dug Out (where Grant was already established) every Wednesday,

and became Bristol's first New York-style sound system. They were accused by some

of destroying the city's live music scene because of the popularity of their parties. Talk

to someone who went to the Dug Out and they will immediately become misty eyed

and mention that larging it is not what it used to be.

The

Dug Out is

remembered fondly by everyone who went there. Bristol didn't have a wide open

nightlife culture to rival New Orleans or Kansas City, it did have one club, the

Dug Out, where black and white mixed fairly freely, unusual in a city centre where

straight clubs like Romeo and Juliets used to operate an unofficial quota system

in allowing entry to black men. And whatever the theory, the Dug Out really does

play a big part in the story. It also links together the mini-boom that Bristol's

musical culture did experience, in the post-punk bohemian fringe of the Pop Group,

Pigbag and Rip Rig and Panic in the early eighties, with the sound-system crew

that went on to become the basis of the Bristol sound, the legendary Wild Bunch. The Wild Bunch formed

around the scene that had developed at the Dug Out in 1982 or so. They then started

to DJ at the Dug Out (where Grant was already established) every Wednesday,

and became Bristol's first New York-style sound system. They were accused by some

of destroying the city's live music scene because of the popularity of their parties. Talk

to someone who went to the Dug Out and they will immediately become misty eyed

and mention that larging it is not what it used to be.

Gary Clail was there, terror funk singer Mark Stewart, and a host of punks, rastass

and b boys, surrounded by a fog of spliff. One of the bunch, Nelle Hooper, left

to join Soul II Soul and co-produced their first two albums. The rest became Massive

Attack who in classic laidback Bristol fashion released one single in 1986 and

finally followed with an album some five years later having joined Cica records

for a sum of around £270,000. The album Blue Lines was one of the finest,

most accomplished and orginal dance albums.Just when the hype was at it's highest,

with camera crews swarming after Massive Attack. most people could barely find

a decent club night to go to. The Dug Out was shut down by the authorities and

the loss of this legendary early 80s club was still keenly felt, though for a

while the scene moved on to the Moon Club on the edge of St Paul's.

Gary Clail was there, terror funk singer Mark Stewart, and a host of punks, rastass

and b boys, surrounded by a fog of spliff. One of the bunch, Nelle Hooper, left

to join Soul II Soul and co-produced their first two albums. The rest became Massive

Attack who in classic laidback Bristol fashion released one single in 1986 and

finally followed with an album some five years later having joined Cica records

for a sum of around £270,000. The album Blue Lines was one of the finest,

most accomplished and orginal dance albums.Just when the hype was at it's highest,

with camera crews swarming after Massive Attack. most people could barely find

a decent club night to go to. The Dug Out was shut down by the authorities and

the loss of this legendary early 80s club was still keenly felt, though for a

while the scene moved on to the Moon Club on the edge of St Paul's.

Indeed, its reputation has reached quite mythic proportions, its role in the story of the Bristol sound becoming comparable to that of Minton's Playhouse and the clubs of 52nd Street in the history of bebop. Of course, like its historical forbears, it was also a dive, and it operated as a jazz club long before it became associated with hip-hop, with Bristolian jazz musicians like Keith Tippett and Larry Stabbins (of Working Week) paying their dues there by sitting in with the resident trad and mainstream bands while they were still at school in the mid-sixties.

Located on the site of what

is now a Thai restaurant, in Park Row, just across the road from the university

at the north-eastern edge of Clifton, the Dug Out lasted until 1986, when the

police and the Park Street Trader's Association got it closed down after a number

of violent incidents in the vicinity. During its high point in the eighties

it was less a discotheque - its nominal function - than a rather gloriously

dingy hang-out, a rabbit warren of inter-connecting cellar rooms that gradually

grew to include a video lounge and a second clubroom upstairs, called, of course,

Upstairs. Everyone remembers the carpet, which would stick to your feet like

some particularly viscous oil-based material, the fibres trying to follow you

as you moved. Significantly, as noted, it was a place where downtown and uptown

mixed, an almost unique space within the carefully-patrolled and segmented city

where black kids from St Paul's and the estates met Clifton trendies and those

from the white working-class tower blocks of Barton Hill and the outlying districts.

Whether they actually did mix much is a disputed point to be returned to later,

but at least the possibility of social miscegenation was there, even if it might

not go much farther than a white boy or girl buying a 'quid twist' of grass

from the black man who stood on the stairs.

'For me the Dug Out

was like a legendary hang-out which was almost dangerous and exotic', remembers

Massive's Robert Del Naja, who was introduced to the other members of the Wild

Bunch there as a young punk into the Clash and reggae in the early eighties.

'Everyone talked about the danger and the trouble there and the history of it

being a jazz club in the sixties. Suddenly it was like everyone was saying "Let's

go down there and have a look". You'd go drinking in Clifton or Montpelier

and then go down the Dug Out, and it became an every-day-of-the-week thing,

the sort of club you'd go to Monday to Saturday. You'd do whatever you did in

the day and then, like about eight-thirty go down the Dug Out, sit in the video

room and watch a movie and then, by the time you turned round it was eleven-thirty

and you were ready for a night out till two in the morning.

'For me the Dug Out

was like a legendary hang-out which was almost dangerous and exotic', remembers

Massive's Robert Del Naja, who was introduced to the other members of the Wild

Bunch there as a young punk into the Clash and reggae in the early eighties.

'Everyone talked about the danger and the trouble there and the history of it

being a jazz club in the sixties. Suddenly it was like everyone was saying "Let's

go down there and have a look". You'd go drinking in Clifton or Montpelier

and then go down the Dug Out, and it became an every-day-of-the-week thing,

the sort of club you'd go to Monday to Saturday. You'd do whatever you did in

the day and then, like about eight-thirty go down the Dug Out, sit in the video

room and watch a movie and then, by the time you turned round it was eleven-thirty

and you were ready for a night out till two in the morning.

What made the Dug Out good

was that it was a place where you could chat, drink and communicate and get

into the music. Nowadays you go out on a night till six in the morning and you're

completely wiped out the next day, but in those days you could go out six nights

a week, drinking Special Brew and smoking Red Leb, that was the combination.

In terms of learning about the music the Dug Out for most people in Bristol

was the only place you could mix. You had the pubs up in Clifton which was trendy,

the Rip Rig and Panic, M4 sort of crowd, or down St Paul's at the blues, those

were the two choices; or you were going to the Dug Out and mixing. That's why

the Dug Out was such a threat, that's why it got closed down. I mean they blamed

it on trouble and the rest of it but there was much more trouble going on down

the centre, more fights, more stabbings, more shops being urinated on, shop

windows being put through. It was more like the Dug Out brought the black people

out of St Paul's into Clifton, and the traders - it was them

who got it closed down - couldn't hack it at all. And nor could the Old Bill

because it meant things weren't contained into one area and it freaked them

out, it was anarchy you know?'

What made the Dug Out good

was that it was a place where you could chat, drink and communicate and get

into the music. Nowadays you go out on a night till six in the morning and you're

completely wiped out the next day, but in those days you could go out six nights

a week, drinking Special Brew and smoking Red Leb, that was the combination.

In terms of learning about the music the Dug Out for most people in Bristol

was the only place you could mix. You had the pubs up in Clifton which was trendy,

the Rip Rig and Panic, M4 sort of crowd, or down St Paul's at the blues, those

were the two choices; or you were going to the Dug Out and mixing. That's why

the Dug Out was such a threat, that's why it got closed down. I mean they blamed

it on trouble and the rest of it but there was much more trouble going on down

the centre, more fights, more stabbings, more shops being urinated on, shop

windows being put through. It was more like the Dug Out brought the black people

out of St Paul's into Clifton, and the traders - it was them

who got it closed down - couldn't hack it at all. And nor could the Old Bill

because it meant things weren't contained into one area and it freaked them

out, it was anarchy you know?'

The Dug Out was the only place to go', remembers the photographer Beezer, who

took the pictures of the Wild Bunch there in the early and mid-eighties, as

the group gradually came together after Grant Marshall began working as the

Dug Out's DJ in 1982. 'It was a different crowd every night of the week and

it was, like, thirty pence to get in, maybe seventy-five at weekends. I started

going there in about 1977, when I was thirteen. You had to lie about your age

but no one was really bothered. There were all kinds of scams. Once, a local

free sheet newspaper had advertised a free drinks token for the club and we

knew the person who was delivering them so we nabbed the lot, about five hundred

copies, and kept presenting the tokens for free drinks. Sometimes the barmaids

would give us a drink if we just pushed a button or five pence over the counter

until the manager found out and banned us.'

'You'd

walk in and immediately be confronted by Max, the doorman, who used to just

sit there and look you up and down', remembers Oli Timmins, a designer who produced

artwork for the first Smith and Mighty releases and who continues to collaborate

with Robert Del Naja. 'You'd show him your little membership card, your passport

to late-night drinking, and then you'd walk down the stairs and end up in the

middle of the dance floor, where no one was dancing except maybe Sapphire. You'd

buy quid twists from the black guy who stood on the stairs, little bits of paper

with a few bits of grass - always grass - mixed in. that you'd get three or

four spliffs from. There was always a fight. Every night there would have to

be a fight and it would clear the place for a few minutes until someone came

and sorted it out. Sometimes people would let off canisters of CS gas and everyone

ran out.

'You'd

walk in and immediately be confronted by Max, the doorman, who used to just

sit there and look you up and down', remembers Oli Timmins, a designer who produced

artwork for the first Smith and Mighty releases and who continues to collaborate

with Robert Del Naja. 'You'd show him your little membership card, your passport

to late-night drinking, and then you'd walk down the stairs and end up in the

middle of the dance floor, where no one was dancing except maybe Sapphire. You'd

buy quid twists from the black guy who stood on the stairs, little bits of paper

with a few bits of grass - always grass - mixed in. that you'd get three or

four spliffs from. There was always a fight. Every night there would have to

be a fight and it would clear the place for a few minutes until someone came

and sorted it out. Sometimes people would let off canisters of CS gas and everyone

ran out.

'Everyone, absolutely everyone used to be there, and they'd be there every single night of the week. Because you paid a membership, it cost nothing or nearly nothing to get in, and the drinks were at pub prices and someone would always buy you a drink. It had an air of slight dodginess and it was a little bit scuzzy, wHich was good. Eventually, in the mid-eighties, the music started to come to the forefront, with 2 Bad Crew and Grant, and it started to change a bit and people began to dance, though not much. I remember being rather perturbed because I was into the Clash but I also liked disco music and they didn't seem to fit together, but then the Clash started to do disco-type things. Dub was really the saviour of it all, because it brought all the different things together.'

'I'd go there when it opened

and only just make it home after it closed. On the last week before it closed

down they had free drinks from nine to ten o'clock and you'd go to the bar and

order like ten tequilas. It wasn't like clubs today, no one frisked you on the

way in, and you could go on your own and be sure of meet- ing someone that you

knew. The owner. Brian Jones, was a great guy. He was into offshore powerboat

racing and he sometimes used to park his boat out- side the club. He obviously

made so much money that he let people do what they wanted, as long as they were

within reason. The atmosphere was a lot to do with the kids who went there,

who tended to be the more street-aware kids, who didn't want to dress up for

a disco but wanted to wear their ripped jeans, and because of that it did become

a kind of melting pot with people from all over the city and where it didn't

matter if you were black or white'

Paul Johnson remembers it differently: 'At the Dug Out everyone who was someone

was there, it was the place to go and be seen, but there was absolutely no conversation

across the social boundaries and themelting pot thing is an illusion. People

from differentareas would go but they wouldn't get on. Nellee was there

with the Clifton people - saying "ya" instead of yes, but I felt that

they treated me like I was thick because I came from St Paul's. I didn't like

the Clifton music anyway - Pigbag, Rip Rig and Panic and them - it was too trendy.

I liked funk bass and heavy beats, like Parliament and Funkadelic.'

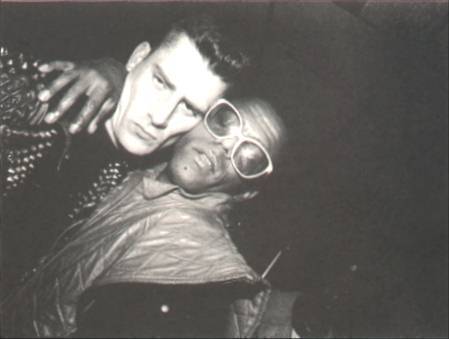

Sapphire (right) & friend @ the Dugout, 1984

'I used to go to the Oasis, on the gay scene', remembers Sapphire, 'and one

night I says to my friends, this is a bit boring, let's go down the Dug Out.

"You're wearing a dress, you'll get beat up" they said, but I went

in there and felt the vibe, got on the dance floor, cracked open my amyi nitrate

and hoisted my dress over my head. You could do anything. To give you an idea

of how free it was I used to pick guys off the dance floor and give them blow

jobs in the toilets. One night I had two guys in the cubicle and the manager

was standing right outside the door and he could see the tail of my coat on

the floor. I wasn't bothered and just went out of there smiling, but the guys

were a bit scared about coming out.'

'I used to practically live there, it was my home and when it closed part of

my life was gone, like taking off an arm. It was ahead of its time in terms

of everything. In those days clubs were quite cliched but in the Dug Out you

had students, pimps, queens, decent folks, drop cuts, a whole mixture of people

there to have fun. People did mix, but it all depended who you were. I was black

and gay and I would mix, but there would be groups of black guys who would just

sit and smoke their spliffs, or stand around looking cool - if you spilled a

drink on them they made you pay for the dry cleaning the next day. Even on a

Monday night it was packed. People tell me that they would go because there

were a lot of nurses and they were supposed to be easy and randy when they got

drunk ... in the end there were too many young black kids from St Paul's selling

drugs to all the white kiddies, and that gave the police a better chance to

close it down.'

Marc Crewe, who was the rock editor of the local listings magazine Venue throughout the period. The irony of the club was that really it should been in St Paul's, not Clifton. It was the only place in the city where you got such a mixed crowd a roots of what it became began in the punk days they even used to have punk bands playing live were always terrible, and they played reggae breaks, which all the punks as well as the rastas who went there were into. The police really used to though, because it was letting the black kid Clifton. I remember one night when there stabbing outside the club somewhere, whic nothing to do with the Dug Out, but about police came in and rounded everyone up, {them outside and searching them while the blood from the guy who had been stabbed was pouring down the gutters.'

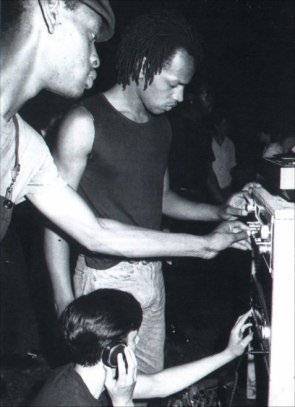

Grant, Nelle and Milo at the Dug Out 1983

When hip-hop took off in the early eighties, it didn't enter a vacuum (or at

least it did so only for those listeners who were very young at the time), but

rather it was received within the club culture of the Dug Out, and other venues

like the Dockside Settlement in St Paul's, into a scene where roots reggae,

love and dub were already well-established, along with the late-punk sound of

the Clash and the contemporary black music of soul and jazz-funk that any club

would have been playing as an incentive to dancers. What began as the loose

affiliation of the Wild Bunch had connections which substantially pre-dated

the emergence of hip-hop, and their sound system reflected this, mixing reggae,

funk and electro together quite (naturally. Miles Johnson, Nellee Hooper, Paul

J and Rob Chant (later to play with Smith and Mighty) had already been in a

post-punk band called Youth; Hooper had played percussion with Pop Group boho-funk

offshoot, Maximum Joy, and also with Pigbag, with whom he appeared on Top of

the Pops. By the time Miles Johnson came back from a short spell in prison in

1982 (for which, so it's said, he took the rap for someone else) hip-hop had

truly happened and the heroic era of the Wild Bunch began in earnest. "Hip

hop was the first music that really brought the races together. especially in

this country, because it didn't really belong to any of us, we were all borrowing

it", says Mushroom.

Roni Size: Innovate he does, but he's always ready to acknowledge his influences

which started in the home and, not unusual for a Bristol artist, took in the

Dug Out. Or at least the pavement outside. "I could never get into the

Dug Out. I'd go along and I'd have to stand outside and inagine what was going

on inside. I could hear the sounds but never really new what was actually happening.

It's a part of my inspiration though, that place, the music that came out of

it. But my school, really, was the sound systems. There would have to be places

like The Mill, Carnival and Wild Bunch parties, and there were clubs like Raquel's

on Frogmore Street on a Saturday afternoon, all playing stuff that influenced

me. Back then there was the Wild Bunch who had their own style and records,

and then there was City Rockers playing in a different style, and 2 Bad Plus

One and UD4...all these crews had different styles and records. It's only really

Wild Bunch that people hear outside of Bristol, but all the different crews

were doing great things."

Nelle Hooper

Undoubtedly one of the instigators of the Bristol Sound, Nelle Hooper was voted

number one in the venue top 100 poll three years ago where he was applauded

for his contribution to his home town. Before he was a member of the legendary

Wild Bunch, Nelle (probably not the name his parents gave him) also

played in Mouth, Maximum Joy and Pigbag. When members

of that posse formed Massive Attack after an abortive tour of Japan, he moved

to London to hook up with Jazzy B in Soul II Soul.

Those two acts changed forever the way British dance music was recorded, produced

and received. He

did return to the Massive Attack fray to twiddle the knobs on the Protection

album. Despite acclaimed

and, let's face it, lucrative production credits for Bjork, Sinead O'Connor, All Saints and Madonna

amongst many others, Hooper has managed to stay out of the spotlight for most

of his career. He has never been interviewed in the press and there are few

photographs of him. We don't know where he his now either but a fair guess would

include supermodels and a very happy bank manager. A rumour that he lost his

wallet on the downs, during a recent visit home prompted record numbers of visitors

to the greenbelt. More power to him, we say. His

great mistake was inflicting the dulcet tones of then-girlfriend Naomi Campbell

on the world.

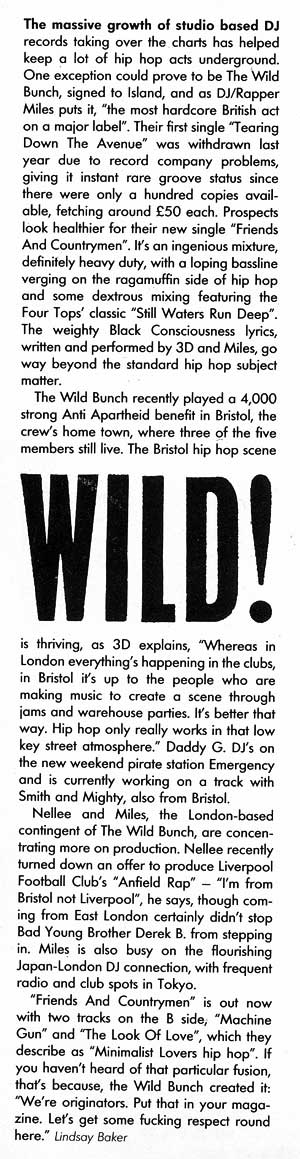

British Underground Music i-D magazine. March 1988

FOR THE FIRST TIME BRITISH CLUB DJS ARE MAKING RECORDS. THIS IS THE CULMINATION OF FIVE YEARS WORTH OF HIP HOP, HOUSE AND RARE GROOVE. ITS NOT BRITISH HOUSE OR BRITISH HIP HOP BUT BRITISH UNDERGROUND MUSIC. BUM FOR SHORT, ITS GROWING UP FAST.

STORY BY JOHN GODFREY

PHOTOGRAPHY BY KEVIN DAVIES

From Chris Hill's Rente Santa to Steve Wright's Alright (and let's not forget Terry Wogan's Floral Dance), British disc jockeys' contribution to music has been a bad joke. Bad because novelty was deemed to be a peculiarly oafish occupation that the British excelled at, and a joke because their accountants had the last laugh. The belief was that disc jockeys (aka jocks) had to be personalities, and that mucky innuendo or the dedication for Sharon's 21st would ensure that nobody cared what they were dancing to because everybody was too busy laughing. Everybody danced The Jibe, where congas and a pint of sansria followed a disc jockey's cheerleader patter into The Birdie Sons or The Fatback Band's I Found Lovin'. This was a device that early soul disc jockeys like Chris Hill used to ease the terrace antics of the dancefloor into jazz-funk (rekindled by Steve Walsh's appalling anthemic rendition of I Found Lovin') and a cloak to hide Radio One's pop triteness. The essence was good clean British Fun; nudge needs wink wink, no soul please we're British.

Of course, there has always been the occasional mix DJ like Frossy, and Tony Prince's Discomix Club created an alliance of DJs who could match bpms with unerring blandness; but until hip hop (and more recently House music) turned disc jockeys into DJs and showed what was possible, the most successful record made by British DJs was Convoy by Dave Lee Travis and Paul Bumett.

When the first rap films introduced Britain to the Bronx and record decks became 'wheels of steel', a thousand kids ruined their Chic records in their bedrooms before they realised what a slip mat was, and then began copying New York in earnest. As the rest of Britain fumed their backs and electro became a term of abuse, UK hip hop was bom in isolated house parties and home made studios. But it wasn't until clubland took to hip hop with all its fashion fittings and b-boy style that anybody else started listening.

It took Run DMC's chart assault for major record companies to realise that there was money to be made, but the knee-jerk response was to license US imports while watching small labels like Streetsounds (now DM Street- sounds/Westside), Rhythm Kings and more recently Music Of Life, attempt to foster homegrown talent. Apart from little money, few facilities and no major label interest, British hip hop always suffered from an inferiority complex and an infancy which was forever trying to compete with New York; a history of producers who thought hip hop was Bugs Bunny disco, and the wholesale adoption of b-boy slang. You were either illin' or chillin', and always def not dumb. But two records broke the rap mimicry without having to revert to the ham fisted Brit-building of the Three Wise Men. Derek B's Get Down (Music Of Life) and The Cookie Crew's Females (Rhythm King) both worked because they were listening to club dancefloors - not New York's, but London's.

Derek B's Get Down was the result of five years of club DJing experience at warehouse parties and the Wag Club (where Derek still DJs on a Friday night), of knowing what people wanted to dance to, and more importantly what people wanted to dance to at the time, the right time. Its use of James Brown's Funky Drummer, Greedy G and The Jackson's I Want You Back, and its rap through London clubland name-checking clubs, DJs and warehouse sounds was a language that clubbers understood. Females was a rap over an essentially 'rare groove' backing track, an unashamedly commercial record prompted by their producers', The Beatmasters, awareness of London's club soundtrack and a logic that had employed House on their previous single Rock Da House. Get Down and Females have been the two most successful British rap (not hip hop) records to date.

M/A/R/R/S' Pump Up The Volume reaching Number One was the most important event in recent British dance history. Not only because its success catapulted sampling into a legal quagmire, but also because it would not have been possible without two club DJs. What was originally a collaboration between the bands Colourbox and AR Kane became a transformed piece of dance collage in the hands of UK Mixing Champion CJ Mackintosh and Raw DJ Dave Dorrell. Pump Up The Volume was the most visible sign that British club DJs had taken their creative impulses a step further than ransacking Seventies funk for rare grooves. Promoted nowhere but in the clubs it was the most emphatic demonstration yet of the power of the dancefloor.

M/A/R/R/S DJ David Dorrell says, "The nature of London clubs is much more amateur than New York, It goes back to its warehouse party roots and one-nighters, plus the fact that the majority of the music is imported. Thus, there's a consequent lack of passion about the music being played and because it's so diverse there is no continuity. It's taken DJs this long to absorb what they've been playing for five to eight years, and I don't think that until last year British DJs were as technically adept as New York. But now DJs are making records because it's an outlet for their creative urges. And British DJs are doing far more interesting things than the Americans and are far more willing to take risks." But G, his M/A/R/R/S partner in crime has been scratching and mixing records for Serious Records, 4th & Broadway and Music Of Life for two years. Ever since CJ started spinning records at the Flim Flam in New Cross three years ago he's been a club DJ exception, one that entered the UK Mixing Championship run by the Discomix Club only to walk away with the title. Working with Dave Dorrell on the M/A/R/R/S follow-up single and the rock/rap compromise of Nasty Rox Inc (managed by Dorell, their debut single and album are imminent), CJ's solo album on Music Of Life should be out soon.

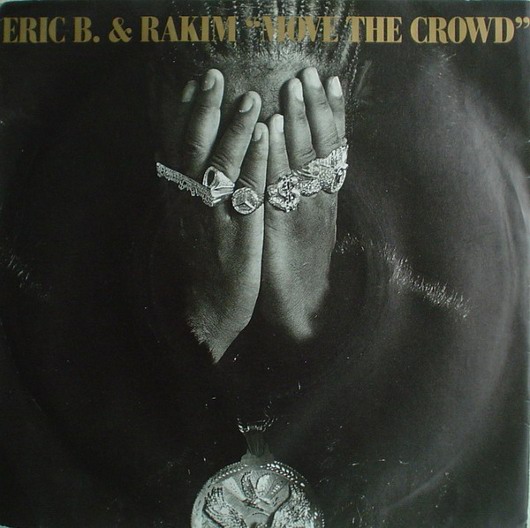

It was CJ who was first offered the chance to remix Eric B & Rakim's Paid In Full but it was the Coldcut remix that took it intothe charts. As Coldcut, Jonathon More and Matt Black released the first British scratch mix record Say Kids What Time Is It? at the beginning of 1987 from the back of a van on their own Ahead Of Our Times label. In all, they've released six mixes that have revitalised club floors and galvanised other DJs into action. "DJs are notoriously lazy, present company included, and all it needed was one or two records to show that it could be done," says Jonathon More. "But now that DJs are emerging on vinyl en masse, i it could have an effect on British dance music in general and UK hip hop in particular. It's a more lateral train of thought that UK hip hop has always needed. But it would never have happened without the £100 keyboard sampler." The advent of the £100 Casio SK1 keyboard sampler has ushered in a new era of user-friendly studio technology that has enabled people who thought quavers came in packets to make records. "Technology has become so accessible that non-musicians can make a record at home. It has a DIY ethic similar to punk/ says the Mud Club's Jay Strongman.

There have always been mix tapes circulating clubland. In Nottingham Graeme Park used to sell his at The Garage, Jeffrey Hinton's motto "there is no such thing as a bad record" has resulted in ten minute tapes of dislocated disco littering floors from Taboo to The Daisy Chain, and from Eddie Richards (Camden Palace) to Steve Rumney (2 Dam Funky) a hundred tapes have been played in clubs that record companies had rejected, preferring the commerical insanity of Mike Reid's (aka The Trainspotters) High Rise. Britain's clubs were a creative reservoir with its fingers on the pause button. And then someone pressed 'play'.

Jonathon More and Matt Black (Coldcut), CJ Mackintosh and Dave Dorrell (Raw), Jay Strongman (Mud Club), Judge Jules (Family Funktion), Mark Moore (Mud Club/Transatlantic/Pvramid/The Fridge), Little Tim (FAT), Jazzie B (Soul II Soul), Nellee (Wild Bunch), Mike Pickering (Hacienda), Graeme Park (The Urban Beat Club), Colin Faver (Jungle/Camden Palace), Eddie Richards (Camden Palace), lan B (Pyramid) and Nicky Holloway (Special Branch), have all made records within the past year. From the Latin House of T-Coy (Mike Pickering and Simon Topping), the pounding disco of Mark Moore's S-Express and the rockabilly hip hop of Jay Strongman, Britain's club DJs are reconstructing the last five years of club floors with an irreverence that could only have been British. Unlike the territorial dancefloors of America, where hip hop and House rarely meet, the diversity of British dancefloors has given DJs the license to mix. Nothing is exclusive and everything is up for grabs. T-Coy's dance fusion has produced a sound that could only have come from the Hacienda; Mark Moore's disco inferno is a hot sweaty night in Heaven dancing to Frankie Knuckles, Taffy and Mantronix; and Jay Strongman's cut-up mix is inspired by Double D & Steinski but with warehouse roots that neither of them would understand. "Until the Coldcut records came along there was no dance record that really reflected British club culture," says Jay Strongman. "Their use of The Jungle Book's I'm The King Of The Swingers was an immediate reference that clubbers could react to because it's been a big hit in the clubs for years. I'm trying to go even further back with the rockabilly bass-lines I used to play at the Dirtbox. It's paying tribute to my roots."

This is a manifestation of club culture that has little respect for precedent - and isn't concerned with form. British hip hop's problem was always the label, producing straitjacket rap that didn't want to explore any other avenue; and British House is in danger of becoming a copycat beat conceived stillborn in the studios. In the States, club DJs have always been involved in the making of records from the early Salsoul remixes to the packaging of Jellybean Benitez as an artist. In Britain, DJs have traditionally joined record companies as A&R men. The lack of any British producer who has understood the dancefloor is a direct result of them having never gone near one. Whether record companies will realise this and employ the only people that do, is for the moment, immaterial.

From Ahead Of Our Time Records, deconstruction, Music Of Life, Rhythm King,

Baad Records, Submission to anonymous white labels, there are a new generation

of independent dance labels that are letting DJs like Matt Black speak for themselves:

"We're British Underground Music - BUM for short." It's a loose term

that's found favour with everyone concerned, aware of an affinity of purpose

and an anticipation of what may happen next. As Derek B says, "DJs making

records was inevitable, and this is only the beginning." Pump Up The Volume!

Milo

Milo

Miles Johnson

now lives in New York with his Japa wife and two small children, running a company

exporting street-fashion clothes to Japan. He has continued to make music on

a part-time basis and put out a few singles on his own label, but he hasn't

spoken to Nellee Hooper, Robert Del Naja or G Marshall for a long time.

"I went

to Gotham Grammar, and that's when I met Willie Wee [Claude Williams, the Wild

Bunch rapper who was relegated to the role of a driver when Massive signed to

Virgin], but he didn't come into the Wild Bunch until later. G, Nellee &

me did a few things in the late seventies but mainly it was early eighties.

Then I got stuck away in jail, in London while Nellee was in Maximum Joy, and

when I got out in 1982 we got together again and started doing parties in Clifton

and stuff. In the late seventies, pre-hip-hop, we were playing basically reggae,

soul, jazz fusion and punk, new wave. I'd never have called myself a punk but

I liked Wire, PIL, and I know a little bit about the music - I don't discriminate

except where it comes to country music. But punk was hip and there were things

I liked about it, the creative stuff. In jail I listened to John Peel all the

time and he said, 'This is what's happening in New York' and played 'Planet

Rock'.

When I got out we started DJing at the Prince's Court club, pro-Dug Out, and

there was some input of hip-hop but as to the visual side we didn't have anything

to go on, no videos or anything. When we did get to see a video, or maybe the

film of Wild Style, it switched on every part of the information, the sneakers,

the trousers, the graffiti, whatever.

Although hip-hop was American and we were British there was never that sense of not understanding it. We were West Indians dealing with reggae and they were dealing with soul, everyone had the same struggles, the same search for enjoyment. It was wild, cutting like that. What I liked about punk, although it sounded a bit fake, was the same as I liked about hip-hop - you didn't have a regular rhythm and you could be creative with it.

In the punk days we got this band together, me, Nellee, Paul Johnson and a couple of guys from Barton Hill, playing punk or new wave, and that was the first thing I ever did as a group, playing percussion. When I came out of jail Nellee came and started checking me - he was the only one who wrote me when I was inside - and we hooked up. We started doing things naturally and started buying records together. We were doing just parties in people's homes and getting our own equipment. When we started to work as a crew there'd be parties on the downs in the summer and St Paul's carnival where we used to set up, borrowing speakers, right on the front line. As to cutting up and stuff, I mean we didn't even know until Wild Style, and then it was, like, we got to get those turntables. We weren't the first in England, though we were pretty early. We did a little dub-plate recording and we used to play it and people really used to love it; it was just like a master plate, and we had to play it over and over again. It was original music recorded in a studio, with bass and drums, we may even have done it in London.

St Paul's carnival was the

ultimate. We used to play till real early in the morning and we'd have the biggest

set, the loudest system. We ventured up to London and played at Notting Hill

carnival and we did a warehouse party with Nutriment and took a few coaches

up there, stepped out in North London, but not like we rocked it in St Paul's.

We were one of the best crews around, like Mastermind in London and we had a

lot of music from the past, from back in the days, like funk and stuff. We also

did the Language Lab with another crew, which was Mark Stewarts' scene. We'd

mix reggae with hip-hop but it would depend what crowd it was, it's not like

we'd just stick to any format. The London crowd liked the hip-hop and the classic

soul. The Bristol taste was different, you could drop some reggae in there.

But the demographics of our crowd changed until we were playing just to Clifton

types and students.

The warehouse parties in Bristol were amazing; the Red House was the first warehouse jam and that was massive. In 1986 Neneh Cherry called Grant's girlfriend - I was practising at the turntables at the time - and she said Neneh Cherry wants you to go to Japan.' I'd never been anywhere, never even had a passport. We went over there, played a couple of fashion shows, a couple of gigs, and then when I got back home I said we should go back. There were hard times and struggles but in the end we had fun. Neneh Cherry was with the guys from the Face and she got us involved with the top fashion designers, because the Buffalo-type image was strong at the time. What they were really after was good-looking black guys, or at least that's what it seemed to me. I knew Neneh from Bruce Smith, who I had known from my school. He was an American and he came to our school and they started picking on him, and basically, I stopped him getting a big hiding, and he always liked me after that.

When we came back from Japan it all started happening. At one time we were playing three clubs a week and because I used to work in London at Kensington Market during the week I used to have to travel back and forth. We'd do the Dug Out and the Tropic in Bristol and I'd have to go back to London to work in the morning. I also did a little bit of modelling for the cash, because it was good money.

3D? I don't like talking

about that guy. I should have known about him. I liked him up to a certain time

but after he left us and came back from Japan I thought 'Why'd he do it?' We

fell out and I didn't speak to him when he was still in the crew. Everybody

else kept on at me to speak to him and I did but I shouldn't have; he's a big

part of what happened. As far as I was concerned me and Nellee and G were the

Wild Bunch, Willie and 3D were just there for MCing. They were good and 3D's

a talented writer, at that time I was astounded at some of the stuff he was

writing, before he started taking mushrooms and stuff ...

Then me and Nellee moved to London and that was the big thing, but Grant and

the others they didn't want to do it, preferring to stay big fish in small waters.

You could say they were right and we were wrong, but we got the deal with Island

and we wanted them to be part of the group. We stuck our necks out to go to

London; we got an apartment and got a deal, the first British rap group to be

signed to a major, but they wanted to stay where they were. We said, 'Why don't

you come, do some music, get some ideas down?' There was always some kind of

beef because me and Nellee were coming out of London ... I don't really understand

what happened for us to break up. Me personally, I think Delge had a lot to

do with the split of the group. We were growing out of the mindset of being

together but I was into getting something out of this break. Grant wasn't willing

to sacrifice anything, and they weren't willing to see the possibilities. It

was me and Nellee who went to Japan first; we didn't know where we were going

to stay but we weren't bothered about that. I can't say I blame them but, you

know, you only live once, you've got to take the opportunities.

Then I went back to Japan on my own, met a girl and I needed some time out of that scene as there were a things that pissed me off about the Island deal. When I left, there was money in my bank account and when I came back it had gone. That was the falling out of me and Nellee; the guy was the biggest liar to the fullest extent. We were the most honest people in the whole crew but G took the view to believe Nellee and not me, and so me and G fell out. Basically it was about Massive Attack. I was at my sister's house and Nellee phoned and said he wanted to go into production, producing Massive Attack as a Soul to Soul offshoot, but I wanted my own identity, not Soul to Soul junior. I was upfront, Nellee got mad at me and I ain't spoke to him since for eight years. I'm happy for the geezer. It's good to see him where he is. I'm a bit sad Massive didn't do a bit better, though. I thought the record was a bit lightweight. I really believe it; it wasn't what I had imagined it would be. I thought it would be heavier, heavy bass-line music. 3D don't know anything about music, not like G knows his reggae; he's got no rhythm and I guess his influence was in there. The second album I haven't even heard.

I still stay in contact with Mushroom but he's really guarded about me hearing the stuff. Obviously, yeah, he was influenced by me. He was a cute guy and he had a passion for hip-hop, that's what we liked. I feel he's going to be a real successful guy, into the technical sounds and stuff like that. When it comes to sounds he's the man.

Tricky? he came to see me three years ago and we had a disagreement because he invited me over for a jam and then he didn't give me the money. I didn't even know he was large; I didn't want to know. I've seen him on a few magazines over here, the things that college people read like The Village Voice. I'm happy for him. He'll tell you - he can't be anything but honest - I used to teach him stuff through an old relative. I had an old girlfriend I was staying with and he was a cousin of hers.

G hasn't seen me for as long as Nellee has. I like G, he's a nice guy and he's got a heart of gold. He's an easy going guy who doesn't want to do much to make a living. Is there a group called Portishead? Mushroom told me something about them and I saw their name somewhere and I couldn't make sense of it because I knew the place. English rap didn't take off; as for people in Bristol being special I don't know. It's kind of weird, why is it that all these groups have taken off? Smith and Mighty blew up first, Goldie, I know him, that's a real surprise. When I listen to Jungle I just think man, get out of here. I like the beats played at the right speed. But the British music scene is the best in the world, the diversity, the charts ... I'm still doing music, that's my life. I've got about fifty DATs of stuff I've done on my computer; I should put them out. I did a few independent things and just finished a, project with some guys in Harlem called Harlem High. I do music whenever I can. I play people my stuff but I haven't really tried shopping my music. I've done some house stuff for about three years and some hip-hop with rappers.

The business is me and my

wife, not just me. I do a lot of running around, now we've got two kids.There's

so much competition in the market, it's cool though, it pays the rent ... I

said this year might be my year. Hopefully, I'll get over soon.

DJ Milo interview and Wild Bunch story for XLR8R

The mere mention of Bristol brings to mind a signature style of urban music, with Massive Attack, Smith & Mighty, Tricky and Roni Size but a few of the acclaimed artists to come from this unassuming English city. However, the beginnings of its redoubtable scene are a world away from the glossy magazine covers and international fame enjoyed by these now-established stars. Think, instead, of raucous house parties and dingy clubs, DIY ethics and the pure, simple love of great music and good times. Think, in short, of The Wild Bunch sound system.

For an all too brief period in the 1980s, this outstanding collective grabbed the Zeitgeist by the horns and performed a vital role in shaping the future of British popular music, tearing the roof off London’s stylish and aloof hip hop scene, then moving further afield and rocking both the United States and Japan; this at a time when such ventures were all but unheard of within UK DJ culture.

Including such names as Robert “3D” Del Naja, Grant “Daddy G” Marshall and Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles—who eventually went on to form Massive Attack—and renowned producer Nellee Hooper, The Wild Bunch's ongoing influence is plain to see.

However, despite having played a huge part in birthing the city’s unique blend of hazy reggae grooves, headphone-friendly breakbeats, sumptuous, soulful vocals and earthy, idiosyncratic raps, one member has never taken his place in the annals of dance music lore: Miles Johnson aka DJ Milo.

While his peers went on to receive worldwide adulation, the tall, charismatic figure seen so many archive photographs opted for an altogether quieter life. When the crew came to its natural end, he receded from view, eventually settling in New York, where he now lives with his wife and family. Far from being a forgotten man, though, Johnson’s contribution to this memorable period is warmly recalled and any historical imbalance has now, in part, been redressed with the release of his mix CD retrospective, The Wild Bunch: Story Of A Sound System.

A collaboration between the Junior label and UK reissue imprint Strut, this 26-track collection captures something of the vibrancy of those long-gone nights. Blending vintage live recordings of the team in action with an impeccable selection of music—the bumping hip-hop beats of Spoonie Gee and T La Rock, Newcleus and Man Parrish’s early electro, the silken soul of Evelyn “Champagne” King and Mr Fingers’ caustic acid house—it fizzes with joyful energy and provides a valuable lesson in the heritage of British club culture.

The man responsible for this project, Junior’s Paul Byrne, says: “To be honest, the idea came to me in the bath one day. I was just thinking about how there were so many compilations and other things around in the UK celebrating places like the Paradise Garage in New York, but nothing reflecting what went on in our own clubs in the early days, even though it’s equally important in terms of where we are now. It was something that needed to be put right.

“I was only about 12 when The Wild Bunch were throwing their parties so I wasn’t there, but considering the impact they have had, it seemed like the obvious place to start. I began to bounce the idea around and the more digging I did, the more Milo’s name came up. Although the other members have gone on to do great things, he was the one that people who were actually a part of that whole thing remembered best, so we tracked him down and put the idea to him and it all went from there. The bottom line is that he was and still is a blinding DJ and deserves to be recognized for the amazing things he’s done.”

Despite spending the better part of two decades far from the public eye, it is still easy to spot Johnson waiting outside Tower Records on Manhattan’s 4th and Broadway. Now 40 years old, he still has the laid-back style of the veteran B-boy and his voice has lost none of its soft West Country burr.

And so, sitting in an anonymous coffee bar, cradling a paper cup in his hands, DJ Milo starts to tell his story.

“Well, myself Nellee and Grant just got together through hanging around in Bristol when we were young, finding we had things in common and becoming friends through music. You could feel something was brewing there, that something was going to happen when we were kids, but nobody knew what. I guess it ended up being us…”

Bristol’s status as a culturally diverse maritime center is clearly reflected in The Wild Bunch’s eclectic range of influences. Already an established post-punk stronghold, thanks to local bands such as The Pop Group, this scene was enough to keep the average music obsessive busy. But add to this the stimuli provided by predominantly Afro-Caribbean neighbourhoods such as St Paul’s and Montpelier and it is easy to see the city as a musical time bomb waiting to go off.

“It all started back in the early 80s, so musically speaking things were pretty open then. I mean within our little circle of friends, we were all listening to reggae and dub, jazz fusion, disco and funk,” Johnson adds. “But we were also really into things like Gang Of Four, A Certain Ratio, a lot of new wave and stuff like Killing Joke. None of us knew how to DJ or anything, but we just used to get together and play records we liked. Then we started doing house parties together and they became pretty popular because people enjoyed what we were playing.

“In fact, that’s how we got our name, through throwing these wild parties that all kinds of people would come to—punks, nice middle-class kids from Clifton and Rastas from St Paul’s—then one day someone just said ‘You guys are wild… you’re The Wild Bunch’. It stuck.”

Having quickly become Bristol’s most popular sound system, hip-hop would point The Wild Bunch toward even more fertile ground. Then still a trio, Johnson, Marshall and Hooper embraced the new Stateside sound wholeheartedly and earned a reputation as fearsome record collectors, able to find the rarest tracks around.

“We travelled all over the place buying records and always wanted to be the only people with those tunes—or at least the first people with them,” recalls Johnson, with a smile. “The fact that G was working at the best record shop in town, a place called Revolver, did help us there, though. He used to put all the good stuff away so only we could get it. None of the other local DJs had a chance!”

Scoring a Wednesday-night residency at The Dug Out, a down-at heel club in the centre of town, The Wild Bunch found their spiritual home. It was at these fabled sessions that the final members of the line-up would appear—young graffiti artist Robert “3D” Del Naja, long-time friend of Johnson’s Claude “Willie Wee” Williams, hip-hop enthusiast Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles and Adrian “Tricky Kid” Thaws, (who would later become renowned for albums such as Maxinquaye under the name of Tricky).

“They were great days,” Johnson says. “We all brought something different into the mix and it really worked. People had a brilliant time at our nights and so did we. That was what it was all about for us—we were just kids, up to no good, having a laugh.”

The addition of rappers certainly brought a new dimension to the live experience and, indeed, for a while, it looked as though The Wild Bunch could not put a foot wrong.

Not content with riproaring performances across Bristol—causing havoc at the annual St Paul’s Carnival by blocking off the road with walls of speaker stacks and playing epic sets of up to 20 hours—they had to show the world what they could do.

It all started with DJ Milo’s 1985 booking to support their friend Neneh Cherry in Japan. “I remember the first time I went to Japan, it was just mind-blowing—the whole experience was amazing. The records you could buy there and the clothes were incredible, so I thought I had it made,” says Johnson. (His fascination with the country would continue and result in the still-sough-after Major Force single “Return Of The Original Artform” by DJ Kudo and Hiroshi Fujiwara feat. DJ Milo some years later.)

Further trips followed, including visits to the States. However after a third journey to Japan in 1986, egos had grown and cracks had begun to appear in the group.

Perversely, though, it was at this point that The Wild Bunch were asked to go into the studio and commit their sound to vinyl, the resulting single being the now ultra-rare “Tearin’ Down The Avenue”.

For some reason this rollicking slice of UK hip-hop was afforded a limited US-only promo release and then failed to see the light of day. When the time came for Island/4th & Broadway to put it out in the UK in 1987, the lead track was substituted for the alternative “Friends & Countrymen” and the record sank without a trace. However, turn to the B-side of either 12-inch and Johnson’s importance becomes clear. It was his idea to update Burt Bacharach classic “The Look Of Love” with luxuriantly bass-heavy hip-hop breaks and winsome jazz instrumentation. In doing so he laid down the blueprint for what was to become “The Bristo Sound”, so much so that the vocal was even sung by a young Shara Nelson, who would feature heavily on Massive Attack’s timeless 1991 album Blue Lines.

By then, though, three years after it had begun, The Wild Bunch was all over bar the (often literal) shouting and its members slowly went their separate ways, Hooper changing camps and linking up with London’s Soul II Soul, whose era-defining 1989 LP Club Classics Vol. 1 he would go on to produce, and Marshall, Del Naja and Vowles forming Massive Attack.

But looking back, Johnson has no regrets: “I’m happy with the way things turned out for me and I’m glad for everyone else,” he says. “Although I’ve been out of the game for a long time, they’re all still my boys. I suppose I just never wanted to make it big, playing records was what I wanted to do, not be a pop star. It’s taken a while but I’m actually working on a lot of music at the moment. It feels like the time’s right and I’m loving it again.”

And as the conversation takes a final turn to those seminal nights at The Dug Out, he adds: “Thinking back, they really were wicked days, the kind you never want to end—good times, nothing complicated, partying for partying’s sake. I wanted this album to reflect that. Even then, although I had no idea what it would all lead to, you could feel that something really special was happening. I never thought that people would end up wanting me to put together compilation albums about what we were doing, that it would go into history or anything like that. You just knew that you were part of something really good…

Now resident in New York but found mostly in Japan where he DJs extensively.

(Playing at the Detroit Electronic Music Festival)

"DJ Milo was next. I made my way over to the High Tech Soul Stage and caught the very end of DJ Fusions set before Milo went on. He was spinning straight up techno. Sounded good, but I was too pumped to hear Milo to really get into it. Fusion introduced Milo and eveyones face in the crowd had a smile. Everyone there to see him was geeked. His mix was flawless and a huge breath of fresh air considering the rest of the festival was pretty much all house and techno. I can't even begin to explain to you how loud, yet crisp the bass was in his mix. It was overwhelming, but sounded perfect. His set was only about an hour long, but packed with the best mixing I heard all night. "

DADDY G

DADDY G

"We saw hip hop arrive

from across the Atlantic. It's a good feeling, knowing you've been in on a scene

from the start. We were DJing, setting up sound-systems, chatting on the mic and

learning as we went."

"The Wild Bunch was all

about being on the road rather than in the recording studio, we were basically

DJs who occasionally introduced live instruments like drums and bass into the

show. There were loads of reggae sound systems around at the time but we were

the main jamming system with a bit of everything thrown in, there was always a

very mixed and wide range of people coming to our jams. We've never aspired to

please little sections like a pure soul or reggae or hip hop crowd, we've always

done our own thing, mixing in punk or rock n roll or anything, people just get

into what's happening.

Willie Wee

Willie WeeWillie Wee was an original Wild Bunch rapper who went on to an unstructured, part-time role in Massive Attack. He contributed a couple of lines to Blue Lines and described himself at times as tour manager and vibes master. He is a well known Bristol club face, running raves and parties. Rapped with Massive Attack on the Protection Sound System tour. His real name is Claude. Basically he is an all round nice guy.

3D

3DAbout that time (1982) I'd met Miles and Nelle through various people, they were socially quite legendary, quite trendy. At that time me and my mate Pat Morrison used to go up to London to buy reggae twelves and I had quite a good collection of brand-new imports and all the early hip-hop stuff, really good shit, and cos G's the DJ down the Dug Out, and Dom and Milesy and everyone was there, I got to know them and to hang out and talk about music. It was new and it was exciting and the hip-hop thing was happening. Then the Wild Bunch started playing parties, the first thing was an illegal party on the downs in the summer of 1983. And the people who came to it loved it, and then there was warehouse parties, just booking out warehouses, and we'd play the St Paul's carnival, the Dug Out on a Wednesday and warehouse parties around the West Country.

As to starting to make our own music, in those days it was so different, the scene was run by an indie crowd which was very new wave, alternative rock, like four blokes with guitars. The dance thing hadn't developed in terms of being able to turn over music quickly like you can now, so it was a case of Nellee and Miles and G knowing people who had studios and getting in there and applying the logic of being a DJ, making music out of bits of other people's music and putting lyrics over the mike in a rap or reggae way, quite naive in an almost copycat way, same as any band would start. With every new rap record that came out it was, 'Have you heard that new rap record?' and everyone'd say 'Oh yeah, I'm going to do a rap like that.'

The DJs would go out and hunt for the same breaks they heard other DJs cut up in America or on records, all the classic breaks like 'Good Times', every DJ was doing that, every rapper was doing Sugarhill things and then getting into more modern stuff like Run DMC, Eric B and Rakim and Slick Rick. And of course you've got to remember during all that whole thing was the massive tradition in England of the Jamaican toasting scene. During those early hip-hop days you had Saxone and Coxsone and all those sound systems and Tipper Irie and Philip Levy and all those people and it was totally inventive poetically on the mike in that way. So all those things were happening together and I suppose the reggaethings were happening together and I suppose the reggae tinge and the dub tinge kept it English, or Caribbean English rather than being pure New York. And of course the break-dancers were breaking and graffiti artists were copying the Wild Style moves. When SUBWAY ART came out that ended my interest in graffiti because eventually everyone had a sketchbook, everyone was an artist and the whole thing became so faddish and ridiculous that no one was doing what was the most important thing, which was painting illegally on the street, which was the exciting thing about it. In terms of being in the Wild Bunch, there was a million DJs around suddenly and a million rappers and though it didn't force you in the studio, it kind of nudged you along. There was so much copycat business that you wanted to do something to establish yourself as an individual again, and you couldn't do that in the same way as everyone else was doing, so being in the studio was something which had to be a progression.

The first thing we did was Tearing Down the Avenue", a demo we did in the studio. We went to Japan with it and did some recording there and did a tour which was quite a big thing because when we came back it meant that there was two choices. Nellee and Miles being more cosmopolitan than me and G and Claude at the time ('cos Mush was on the sidelines at the time, I suppose everyone was treating him as an apprentice DJ, although he'd hate me to say that, but that's how it was), they wanted to go to London, but the rest of us weren't ready for it. And when we came back I got chucked out of the clan. I missed my girlfriend and I came back and they threw me out. It was my first experience of touring and I didn't like it.

The Japan thing came about because of contacts in London, I think it was Bruce Smith who was in Rip Rig with Neneh and stuff, and he had a lot of contacts there. And when we came back Nellee and Miles decided it was time to go to London and the rest of us said no, we're staying here, being younger as well, and that was when the Island thing came about, 'cos they took the demos there. It was such a trendy scene and the Bristol-London connections were quite strong on that level. Neneh was starting to appear in terms of an artist and all that was going on, the whole Face thing, the Buffalo thing was large.

I stayed in Japan for about a month and the rest of the guys stayed for two. I just left. I left a note saying I couldn't take it anymore, basically, came back and I was gutted and I worked for the BBC for two months washing pots for Angela Rippon. Fucking nightmare. I had to wear little blue overalls and go to Kwik-Save and pick up frozen meat and stuff. It was almost like an exercise in self-diseesteem, where I'd walk up the road in this blue overall with a box of frozen food thinking, 'I was in Japan once, I was in a band you know what I mean? And no one would believe me. I'd even talk about it at dinner, it had completely taken my character down. And then the boys came back from the tour and I was like, can I go in the band again, and they said well we like you, but we're never going to work with you again and I was in ruins, total ruins.

In Japan we played in clubs

and some really pathetic fashion shows where we had radio mikes and we were

dressed up as, like Coco the Milkman I suppose, fucking big clown boots and

milkman's hats and big white coats, with radio mikes - nonsense. We also went

there with the! expectation that we were going to be rich straight off and!

we were just blagging it on frozen pizzas and low-rent old apartments, having

to squat in the shitters and wash yourself in a plastic bowl - it was like a

nightmare. We had no cash, we were so skint that at eight in the evening, we'd

walk two miles to clubs where they'd let you in if you were European or American

'cos you were trendy and there'd be free food there and a free bar; basically

our night out was actually to eat.

Nellee and Miles got themselves kitted out with top apartments 'cos that's the

way they are, they're very resourceful, while I was living in this ski jacket

with Asian flu, taking antibiotics, really having a miserable time. I said 'I'm

out of here.' But the worst thing was, why I blew it, was that I went out shopping

on the day I left and they wouldn't forgive me for that, 'cos I said 'I'm out

of here but I've still got a few hours to go shopping,'and I left with a big

bag of goodies. But as the plane landed at Heathrow I was thinking 'What have

I done?'

When they came back Nellee and Miles went to London and got on with it and got involved in a lot more of that Japanese-London culture exchange. I was way out of it by then but they got this deal with Island and then I got this knock on the door and 'We want you back in', you know, to write lyrics. I'm not saying they're fickle or anything. So then we did this recording and put out 'The Look of Love', which really was Miles' idea, with Shara who was from Adrian Sherwood's posse, and also this rap 'Tearing Down the Avenue', which we had demoed before. Technically, for English hip-hop, it was out there on its own, but Island put it out on import and it was just at the point where Eric £ Rakim was happening and Mica Paris was happening and there was no time spent on it at all. It was out and that was it, it was gone. And then we re-released 'The Look of Love', and did a track called 'Machine Gun' and a track called 'Friends and Countrymen'. It was alright but it didn't really happen, but out of that we met Cameron, and Mush started working on tour with Neneh as a DJ, and doing a bit of work on Raw Like Sushi and they asked me to write lyrics for 'Manchild', which I did and that worked out. During that process Cameron discovered what we were up to and said you guys should get in the studio, funded us and put us up at his place, got us a studio set up and put us in with John Sharp who we nicknamed Johnny Dollar as a piss-take, who became the co-producer of Blue Lines. He was a programmer working for Cameron and they're still together as a team.

At this point Nellee and Miles were signatories to the Island deal but the rest of us weren't. I remember being sat in the kitchen with my dad working out how to put a contract together so I could make sure I got paid for my lyrics. I went out and got some Letraset and designed this 3D-headed notepaper and me and my dad wrote a letter and Nellee said 'What's this bollocks?', and I said, 'So I make sure I get paid something for this record,' and about five hundred pounds sent through the post, and at that time I was chuffed, but at that point they were the Wild Bunch and we were just hanging out in the background providing the flavours.

And then Miles went to live

in America, he disappeared and went to Japan, got married there and now he lives

in New York with a couple of kids. So he was out of the picture and Nellee was

by then firmly entrenched with Soul to Soul and they were large, and Nellee

was large so Cameron put the rest of us in the studio and off we went. Some

of it was bravado, some of it was bullshit, we didn't know what we were doing

but we had ideas and a lot of them were based in the past still. And I got together

with Tricky at that point. The earliest memory of Trick I've got, I remember

meeting him and we did this jam at Trinity and I was on the mike doing this

live version of 'Tearing Down the Avenue' and there was Tricky at the front,

giving it 'Yes!'. He was working with the Fresh Four and we kept up a bit of

a relationship.

Phil Johnson, 1998

Mushroom

Mushroom

Some people get the impression that Mushroom isn't all there. He has a distant,

abstracted air to him, especially compared to the quick wit and easy pisstaking

of Del Naja and Marshall. Conversation can go on around him and he seems to be

oblivious to it until suddenly he comes alive and makes a contribution that picks

up on something that happened ten minutes ago. But his still waters run deep.

He's the real hip-hop heart and soul of the group, his seriousness and dedication

to the beats what impressed the other members of the Wild Bunch when he was just

a kid hanging around. On stage he undergoes a transformation, and as a DJ he can

be remarkably theatrical, spinning round with a record in each arm, expertly manipulating

the decks with a ridiculous ease, cueing up tracks and cutting them up in a blur

of movement.

'The whole thing really started from when I was at school, when I was fifteen or so. I was at St George Comprehensive, which at the time wasn't a very nice place. There was a lot of racism and St George was like on a borderline between St Paul's and Barton Hill and you'd get all the white skinheads and psychobillies plus all the black guys from St Paul's. The police riot vans used to be outside the school with dogs every night because Barton Hill was full of NF skinheads at the time. I first heard hip-hop from this guy's car outside the school and I just checked it out straight away, went and bought the music and that was that. I met G at the record shop, Revolver, where he was working. I saw all these Wild Bunch stickers there and so I said to G, 'Who are the Wild Bunch?', and he said 'I am the Wild Bunch', and it just snowballed from there.

They were playing all over the place and I used to follow them, going to all the hip-hop jams, up in London and at the Dug Out, and all the jams in Bristol. The Dug Out was a bit of a problem because I was only fifteen at the time but G sorted me out with a membership card so I wouldn't get hassled on the door. I started to try mixing straight away, as soon as I came out of school and began buying records. 3PM (an early Bristol mixing crew) were part of it as well, especially Krissy Kriss 'cos he goes back with me a long way, he was the guy who I grew up with and we started doing the stuff with a couple of decks. We used to get together with our records and we made slip mats out of greaseproof paper because we couldn't fathom out what you'd use or where you'd get them from as they were so obscure at the time. You'd get little globules of grease on the records and have to try and scrape them off ....

I didn't know what to do

when I left school so I thought I'd be a chef and I got a YTS job at Michael's

restaurant. Meanwhile, we formed a crew, and did little things ourselves. There

were loads of crews around at the time, like 2 Bad, who were Dom T and Ed Sargent,

who were on a par with the Wild Bunch at the time, but they wouldn't cut it

up so much, they were smoother. I knew the Wild Bunch and I would just be hanging

around and chilling with them when they had their sets and when they weren't

practising I'd mess around with their turntables, and they'd just say 'yeah'.

They were all like ten years older than me and it was really funny just to sit

on a crate and watch these adult guys organize their stuff, like watch them

sort the money out after a gig in Gloucester; there were arguments with promoters,

they had to organize the coaches and I just used to watch it all go on ...

TThere'd be fierce arguments

between them. Everyone was so different from each other and that's what the

arguments came from. I've got to be careful here, about who does what ... Claude