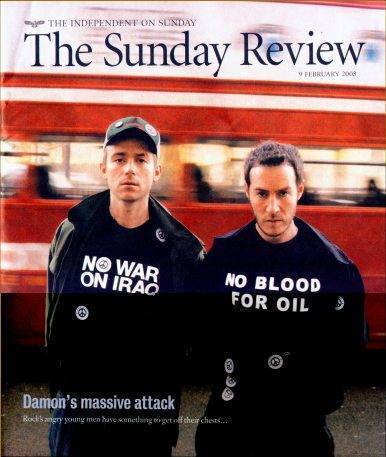

Blur's Damon Albarn and Massive Attack's Robert Del Naja have been reborn as

masters of agitprop, set on using their fame to stop war in Iraq. But are they

the new Bob Dylans or celebs looking for a cause? They tell Emma Warren about

demos, the trouble with Bob Geldofand why they won't talk about their new albums.

Portraits by Greg Williams

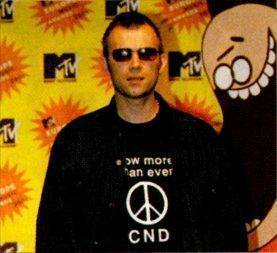

It all started with a black

T-shirt. In Nov- ember 2001, while Hercules C-130X planes were dropping daisy-cutter

bombs on Afghanistan, pop star Damon Albarn picked up a gong at the MTV Awards

in Frankfurt. The 34-year-old frontman of Blur and cartoon hip-hop group Gorillaz

declined to thank the usual roll-call of managers and assistants, and instead

pointed at his top which was emblazoned with the CND logo. "See this symbol,"

he said. "This is the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Bombing one of

the poorest countries in the world is wrong. You've got a voice - use it."

It went down like a bomb the size of a small car.

Today, Albam is eating kippers at the very grand Mandarin Oriental hotel in

London's Knightsbridge, with his new-found political ally and occasional musical

collaborator, Massive Attack's Robert "3D" Del Naja. "You realise

how alone you are when you make those comments," he says, lighting a Camel

cigarette and readjusting his army cap. "It's like you're a bad smell.

People actually turn away from you and are like, 'You're ruining the party.'

All I said was that blanket bombing Afghanistan wasn't particularly prudent."

"Massive Attack toured France when they were testing weapons in the atolls,"

chips in 36-year-old Del Naja, coming over all sympathetic. "I wore my

Greenpeace T-shirt, made statements - and got booed every time I did."

Despite the risks, both are at it again and have become perhaps the UK's most

highprofile "celebrity" campaigners against an attack on Iraq. They've

spent their hard-earned cash placing anti-war ads and last month they lobbied

Parliament. Ten days ago, Albarn was back at the House of Commons giving a press

conference in the company of George Galloway MP (a regular visitor to Saddam

HQ) and the film director Ken Loach.

"I found myself with feeds from live broadcasts in each ear," remembers

Albam of his first lobbying mission. "I was expected to articulate with

the control of a politician and I wasn't at all prepared. We don't sit at home

rehearsing speeches. It's spontaneous and that's how it should remain."

He needn't worry. Neither is likely to get a chillv reception now. Especially

as Albam and Del Naja's recent anti-war statements and high-profile support

for the Stop the War movement are apparently echoed by many in Britain - 77

per cent, according to a Mori poll in January, are opposed to attacking Iraq

without a UN resolution.

"I don't think

there's any precedent for so many people being opposed to something before it

happens," ventures Albam. "And it's not just the public. You've even

got Stormin' Norman saying that it's a silly thing to do."

Del Naja is picking

at toast and drinking tea. "This process [of disarming Iraq] should not

be over in a two-day flash of bombing Baghdad. It's ludicrous; the idea of pre-emptive

bombing sets a dangerous precedent."

"What began as individuals having a sense of unease has become the majority.

We're speaking for the majority now," adds Albam, wanning to die theme.

"Alongside die majority," corrects Del Naja. "Alongside."

When Albam - all intense stare and bounding movements - gets too serious, Del

Naja cracks a joke. When Del Naja, wiry and immaculate in black, begins to sound

like a smoke-fuelled conspiracy theorist, Albarn brings the debate straight

back to the facts. They make an impressive double-act.

Superficialty, it looks like a typical scene in the promotional merry-go-round

that the music industry specialises in: expensive hotel, pop stars pontificating,

journalist there to record words of wisdom. Today, however, two of the busiest

men in British music have taken time out from their hectic schedules (Albam

is recording Blur's seventh studio album, both are in rehearsals for world tours)

to talk politics. Only a cynic would note that the high-profile, media-sawy,

anti-war campaign coincides with Del Naja having to promote Massive Attack's

new album, 100th Window, on which his fellow campaigner, Albam, makes a guest

appearance.

Indeed, perhaps this uncomfortable coincidence explains why, despite the confident

statements, both are looking strangely ill at ease. And when I ask a simple

enough question about how they turned their late-night political debates into

a public, anti-war platform, Albam inspects die peach-coloured tablecloth and

jumps up from his chair in search of a light, while Del Naja scrapes his chairlegs

back on the unlovely patterned carpet with a grimace and makes prolonged hmming

noises.

"I think we should say from the beginning," says Albarn like a seasoned

politician, "that neither of us feels comfortable sitting around talking

about how we met."

"We definitely hmmed and haah-ed about doing this interview," adds

Del Naja softly. "But we really believe in what we're doing. People are

obviously going to question that: is it about vanity and ego or do you really

believe in this as individuals?"

It's easy to understand this reticence when you consider that, musically at

least, both of their bands have been apolitical. And despite a long and venerable

history of protest in popular music, pop-star politics have the ability to make

you the object of ridicule. Take millionaire Sting and saving the rainforest.

Or George Michael, whose incongruous single "Shoot the Dog" approached

British-American relations with all the subtlety of a Big Mac and fries. Politics,

according to the unwritten rules of pop, is about as fashionable as line dancing.

Damon Albarn first met Robert Del Naja in the mid-1990s in Browns Nightclub.

The London celebrity hangout was, insists Del Naja, "the most incongruous

of places" for them to cross paths. However, at the time, Albam was working

with Tricky, who had rapped with Massive Attack, so the pair had some common

ground.

They spent the next six or seven years "knocking about together at festivals"

and, last year, turned their friendship into a bona fide musical collaboration

on the soundtrack of the Irish gangster flick. Ordinary Decent Criminal. Albam

wrote five tracks, and the duo collaborated on "One Day at a Time".

"We tend to disagree a lot in the studio," says Albam, crushing a

cigarette butt.

"Damon tried to do happy things and I find it depressing," burrs Del

Naja.

Then, when Del Naja was holed up at Massive Attack's Ridge Farm studio in Bristol,

recording 100th Window, Albam came to visit. He had written a song for Massive

Attack collaborator and Jamaican reggae singer Horace Andy, but in the course

of a long dunken night, he ended up on backing vocals for the claustrophobic

lullaby and LP highlight "Small Time Shot Away".

This is not the first time

Albarn has found politics. His father and his grandfather were both conscientious

objectors, and he's a life-long supporter of CND. But things deteriorate again

when I try to ask him about this:"That's a personal thing. It defines how

I feel on a daily basis, and how I feel about war. But my individual beliefs

shouldn't be of primary consideration at the moment. Our concern should be,

'Is this war right, or wrong?'"

In July 2000, Albam also travelled to Mali as part of Oxfam's education project

"On the Line". He subsequently recorded with West African musicians

and donated the royalties from the album, Mali Music, to the charity.

But again, Albarn wants to steer all talk back to the current crisis with Iraq.

"There are a million other pressing issues," he says, "but it's

one step at a time. This issue needs to be resolved before any of the other

vast, ever-expanding tier of problems."

But even the hawks have an eye on the power of Albarn. Bizarrely, in 2001 he

was approached by the US military, requesting the use of Blur's hit "Song

2" (which reached number two in the U K and grossed over $2m in the US)

at me unveiling of the new Stealth bomber. Needless to say, he refused.

The Conservative Party probably wish that it had asked Del Naja's permission

to play "Man Next Door" at a policy launch in 2000. It didn't, and

Massive Attack sued, releasing a statement which pulled no punches. "We're

completely fucked off with the Tories," it said. "How

dare they use our music to promote their bullshit?"

Del Naja's anti-establishment credentials are further boosted by an incident

at the MTV Awards - clearly a hotbed of dissent - in 1998, when he and fellow

band members Andrew "Mushroom" Vowles and Grant "Daddy Gee"

Marshal told the Duchess of York to "piss off" when she pronounced

their name incorrectly. A dance magazine recently went as far as declaring Del

Naja "the thinking man's hedonist".

Del Naja's politics have clearly seeped deep into his music. Not only is the

new album (the one we are not talking about) peppered with Arabic strings -

when we met before Christmas, he told me he believed that the West was dominating

the East, and he wanted to reflect that imbalance musically - but the record

features the notoriously passionate Sinead O'Connor.

The irony, of course, is that during the last Gulf War, Massive Attack shortened

their name to Massive to avoid die widespread censorship being applied to radio

and television playlists (Status Quo's "In the Army Now" and John

Lennon's "Give Peace a Chance", for example, were blacklisted). It

worked too: the band's early singles "Daydreaming" and "Unfinished

Sympathy" were hits during August 1990 and February 1991, the period of

the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the Gulf War.

Del Naja puts the decision down to inexperience and being persuaded by management

that they would appear pro-war if they kept their full name (the phrase "massive

attack on Iraq" was appearing in newspapers). It was, he says, "Monty

Pythonesque hysteria."

But that was then. Now Del Naja and Albarn are doing things their way. The pair

recently spent £15,000 on anti-war adverts - featuring quotes from Tony

Benn and the former US Attorney-General, Ranisey Lewis - which ran in the NME.

"We were very careful that the NME ads were graphic, were very black and

white," says Del Naja, who first rose to prominence as a graffiti artist

in the 1980s. "We didn't want to use our personalities or the brand of

the bands. It wasn't a place for our opinion - we wanted to create a place for

debate to encourage people to think about it."

The method seems to be an effective one: Kim Manning-Cooper from CND, who contacted

Albarn and Del Naja after watching Albarn's protest at the MTV Awards, claims

that the ads led 20,000 people to sign an on-line petition opposing the war

and notes that youth membership of CND has increased by over 50 per cent in

the past year. "The numbers of young people attending the demonstrations

have undoubtedly been helped by their support," she says. "While many

public figures are avoiding speaking out against this illegal and immoral war,

I have huge respect for them."

It's all a long way

from the early days of New Labour, when Britpop stars such as Oasis's Noel Gallagher

took tea at Number 10. "The comforting skirt of celebrity approval has

vanished on this issue," says John Rees from the Stop the War coalition,

which is working with Albam and Del Naja. "I'd be very surprised if this

doesn't worry the Government," he adds.

Back in the restaurant,

where a pair of middle-aged Japanese women are cooing over the uniformed guardsmen

riding past the plate-glass windows, Albarn stirs his coffee impatiently. "Anyway,"

he says without any irony, click-clacking around the cup with bruising force,

"That's enough about us."

Albarn and Del Naja

are anxious to promote the Stop the War march that's being organised for 15

February, one of 59 demonstrations taking place on that day in cities worldwide.

"Our primary motivation is that march," says Albam, leaning over the

breakfast detritus and flicking the ash from another Camel Light.

"It has the potential for the country to really demonstrate and reveal

the genuine level of unease about this war."

But can an old-fashioned

demo really halt the drive to war? Del Naja admits to some unease: "I think

the Americans will go to war, but people shouldn't think it's too late. It's

your one opportunity to do something about it. And by creating a demonstration

on this scale, we'll create a precedent which will be referred to in the future.

It's a moment in history that can change the future." Del Naja may sound

evangelical, but this is the newly fired belief of the converted.

Last September, he

joined 400,000 people to march from the banks of the River Thames to IIyde Park.

Hollywood heavyweights Woody IIarrclson and Jack Black milled among the homemade

banners, with slogans ranging from sober exhortations on Palestinian liberation

to the comic, pop-inspired "I'd Rather Jack Than Bomb Iraq".

"Any doubts I

had were erased that day," says Del Naja. "There were so many different

people there, all ages, all ethnic groups, and I thought it was really beautiful.

People who believe

in something prepared to make a statement." He pauses. "What I found

amazing was all these similar people on the other side of the railings watching

and taking photo-,i. graphs. I wanted to tell them to come over."

"Maybe they will now," enthuses Albarn, who was in Morocco, recording

with his co-producer, Norman "Fatboy Slim" Cook, at the time. "I

hope that by the 15th a lot of people who aren't sure or are uneasy, realise

that by committing themselves they will make a difference. I don't think it'll

be possible for Tony Blair to ignore a really big turnout.

"We're not saying

don't disarm Iraq," adds Albam, "we're saying, absolutely, disarm

Iraq, but don't kill hundreds of thousands of people in the process. At some

point, someone is going to let off one of the big fireworks and at that point,

God knows what'll happen. It's unthinkable and impossible to imagine and, above

everything else, we're saying: can't we please find some alternative?"

Del Naja leans back

and grins appreciatively. "You should have gone on Newsnight, mate. I told

you. That was eloquent."

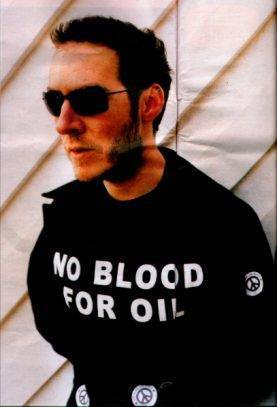

Del Naja has been

quoted as saying that the impending war is all about oil. Albarn agrees. "We

all buy into it every day by getting into our cars and buying 15 newspapers.

We're all complicit in that and we could do with [puts on pub-geezer voice]

taking a bit of time out to think about what on earth we're going to do about

it. But at that point, I'm more likely to go off and play my guitar, because

that's what I do."

"Ah," says

Del Naja, "but will you go off on your bike or get in the car?"

"I'll run,"

say Albam. "I'd run at least one of my journeys, but I couldn't run everywhere

or I'd spend all day running."

Like new kids on the

campaign trail, Albarn

and Del Naja are dismissive of tactics used by their musical predecessors. Albam

certainly has no time for Bob Geldofs 1986 Live Aid concert. Indeed he believes

that the political apathy of his fellow pop artists can be traced back to that

event. "I remember," he says, "being astounded by the fervour

of Geldof and the power and spontaneity of his speech, but also quite sickened

by the endless roll-call of bands, playing their own songs, which created this

vast vat of money, to be poured over unsuspecting people."

Albarn is adamant

that they have learnt from what he sees as their peers' mistakes. "We don't

start bullying people, which essentially is what people like Geldof and Paul

Weller [who spearheaded the pro-Labour Red Wedge coalition of musicians] were

doing at that time. We've learnt that this is not the way to go about things."

They are, however,

trying to drum up support from big-name bands and stars "on a daily

basis" but w^ith the exception of the Mercury Prize winner Ms Dynamite,

Brian Eno and a handful of others, they have run slap-bang into a wall of silence.

"It's not a lack

of support," says Del Naja, "it's just that spokespeople from our

musical peers have been strangely silent. Bizarrely silent. A lot of bands seem

to have pet issues - Fair Trade, anti-globalisation, the environment - and,

cynically, you can see it as part of a branding exercise where the band becomes

synonymous with the organisation. But all those causes, globally, and at every

level, are affected by war in the Middle East."

Worrying about the

public's apathy, Del Naja says, "No one is going to be as political as

they used to be if there's no one encouraging them. But I do think all of us

have become more political since 9/11."

Neither artist plans

to quieten their opinions when their respective world tours reach the US. "I'll

be singing my heart out, mate," says Albam. "I speak with my heart,

I'm very clear about what I believe and that will inevitably be reflected in

the way I'm singing."

"When we started

to show our feelings I had quite a lot of angry and vitriolic messages from

Americans on our website," adds Del Naja. "But that's completely changed

now. We're getting loads of messages of support from Americans saying that what

we are doing is exactly the right thing."

In the 1960s, musicians

who wanted to protest against the war in Vietnam wrote songs. So will Blur and

Massive Attack now be writing albums full of such protest? There is an avalanche

of silence, and much inhaling of breath.

Albarn and Del Naja look at each other and lean back.

Albam: "Ah, you

see..."

Del Naja: "That's,

er, difficult."

"You inevitably

do that," says Albarn finally, "whether it manifests itself in an

obvious way is up to the listener."

"I think both

of us realise that we're open to justifiable criticism and cynicism," says

Albarn seriously. "But at the end of the day, do you [he nods vigorously

towards the Dictaphone on the table] believe this is the right war? Do you?

If not, come on Saturday 15 February, because that's our only way of showing

how we feel."

And with that, pop's fledgling politicos sweep out into the Knightsbridge morning.

The London Stop the War

rally meets at 12 noon on 15th February at Embankment and Goiver Street.

Visit to www.stopthewar.org.uk for

details.