Obscured by Clouds

(Mojo - July 1998)

The Lunatics are on the

grass...Massive Attack and the new psychedelia

A herbal fragrance floats over the Vale of Avalon. A heartbeat throb echoes

round the canyons of inner space. Lo, English psychedelia has returned to earth.

Robert Chapman meets the mystery men at the forefront of the new trip.

"Me and Angelo, our

guitarist, sot stuck in a cave in Padstow," says

Massive Attack's

Robert '3D' Del Naja, talking about one particularly eventful sojourn in Cornwall

to complete the new album. "We'd done a long walk and tried to make it

into this cave before the tide came in. The water went to the back of the cave

and suddenly it didn't empty again, but came back in higher. For one second

I looked at Angelo and thought, This will make the third page of the Bristol

Evening Post: 'Men Die In Caving Tragedy.' I thought, This is what life comes

down to: one silly mistake in a cave, miles awav from your comforts and your

home. There's a warm studio round the corner, everyone sitting in front of the

Pro-Tools with tea and coffee — and here we are arsing about in a cave.

. ."

Somehow, this image

of impending doom seems all too appropriate.

By now the pained circumstances

behind the making of Massive Attack's "difficult" third album, Mezzanine

are public knowledge. It almost split the band, and although a fragile peace

holds as they tour the album round the globe, they still do their interview's

separately. Thankfullv, there is an all-pervading good vibe on the tour bus.

It permeates everything from the technical crew to the musicians with whom Massive

augment their live show. A more relaxed, unpretentious bunch you couldn't wish

to be around. What some people perceive as miserabilism seems to be based on

little more than the Fact that they don't smile for photos or act like arseholes

on aeroplanes. They do, however, get extremely animated when the tour manager

prints off an itinerary of forthcoming World Cup matches. Band members and crew

eagerly peruse the fixtures, working out how to squeeze in viewing between soundcheck

and performance, or precisely how many hours they've got to get twatted in Osaka

between the end of the show and that 3am Jamaica v Croatia kick-on. Half the

band head for the gym or the pool as soon as they've checked into a hotel, and

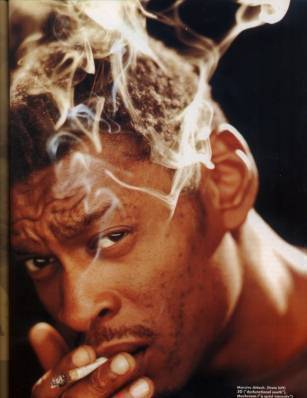

contrary to rumour they're an abstinent lot on the whole. Not Grant "Daddy

G' Marshall, though, who has a little welcoming present rolled as I'm whisked

off to his room the moment I arrive at their Vienna hotel.

"If we weren't

touring we might have all gone our own separate ways by now," he says from

his permanently recumbent posture, stretched to his full six-foot-six extent

on the sofa. "There's a lot of ego in this band and we can all be fiercely

independent people but there's units on the road, which is a good feeling compared

with the feelings we had for each other at the time we were making the album."

Tlouring has obviously refocused and revitalised them. You only have to watch

the stage show to see that. Eight dates into their European tour when I catch

up with them, they are a flawless, finely honed live unit. "We tried to

tour Blue Lines but doing what we'd done as The Wild Bunch, which was bollocks

really," says G, referring to earlier attempts to take Massive on the road.

"It was too rigid. We were going backwards instead of going forward. It's

more organic now."

It certainly is. After

the madness of Naples, then Rome, where 1,500 locked-out punters rushed the

doors, Vienna is a bit more sedate. It's mostly indie kids; appreciative but

cool seems to be the consensus. Munich Coliseum the following night is another

matter. Hip hop nodders, sexy swayers and mad moshers united. The audience weren't

bad either. Some critics, locked into that mindset which dictates that you have

to have four people on-stage all night doing the same thing, are confused by

the sprawling collectivity of it all. Vetran reggae singer Horace Andy takes

the mic for the opening number. Daddy G, 3D and Mushroom (Andrew Vowles) don't

come on until the second number. Then they go off again. And on and off again,

all night. If anything Horace is the star attraction, singing like an angel

on-stage, limbering and birdy-hopping in the w ings even when he's not performing.

When I arrive Horace

is not in the best of moods. He's lent his London flat to a friend with nowhere

to stay. Said "friend' has repaid the favour by running up an £800

phone bill. But by the evening Horace is suitably chilled. I congratulate him

on the best version of Man Next Door I've ever heard. "The band only knew

the Dennis Brown version," he tells me. "I'm singing them the John

Holt version."

"Horace is great,"

says 3D, "really open-minded. It's difficult for him in a sense because

he's got such a massive history and there's people who respect him in London

and Jamaica who could be asking, "What happened to your reggae roots, Horace?

He's not worried about what people think of him even though he's had people

dissing him for it. He's prepared to experiment with the rest of us."

The rest of the band cook up a maelstrom too. Angelo Bruschini, the source ol[Mezzanine's

awesome guitar layers, now drives the dynamics on stage, segueing between the

trancey percussion of Karmacoma and the still joyous Hymn of the Big Wheel without

breaking stride. "Minimal moments and phenomenal moments," as 3D calls

them. Deborah Miller wears the Shara Nelson mantle with aplomb, sending the

regulation shivers down the spine during Unfinished Sympathy as if she's been

doing it all her life.

And then there's Mushroom, seated at the centre, the switchdoctor, conducting

from his twin decks, feet splayed, expressionless gaze fixed on the audience

like he's channelsurfing in front of the telly at home. "I don't really

enjoy touring," he says, despite looking so assured on stage. "It's

nice to go out there and interact with the fans, but I don't enjoy the other

aspects. The bus seems comfy but it gets a bit stinky and dirty" And for

the non-drinking, non-smoking Mush there's the added inconvenience right now

of trying to live on a vegan diet in the land of a diousand winning ways with

a sausage.

Leafing through the recent

press coverage I'm puzzled bv a comment in The Daily Telegraph's review which

asserts that in Bristol "punk challenged reggae's predominance in the late

'70s". It's a cultural topography which neither Daddy G nor this former

Bristol resident recognise. City centre clubs were a reggae-free, black face-free

one back then. If you wanted to find reggae in late '70s Bristol your best bet

was the Saturday disco at the Docklands Settlement community centre in City

Road where you might just hear of a blues party going on later. "Which

is where we got our inspiration for The Wild Bunch sound system," says

G, "but it was all quite segregated then. We could only do parties in St.

Paul's at first, but come the '80s it became a more open city. The Dug-Out Club

was the half way house — that was as far into Bristol as black kids would

go. And white kids then started coming down to St. Paul's. "But not so

much now," he adds darkly. "It's all imploded on itself again."

Why? I ask lazily, naively, monged from the rocket fuel wrapped in Rizia that

he's offered me. G looks up from the depths of his comfy sofa. "Crack.

And that's not a race thing. Crack creates soft targets." It becomes clear

that crack is creating as dangerous a legacy as heroin did in Harlem in the

1930s, and with the same devastating social consequences.

This sense of realpolitik seeps through into Massive Attack's music and lyrics,

arguably into their entire outlook.

All the band members

cite Bristol's legacy' of racism to me at some point. For all its unifying potential,

even The Dug-Out Club suffered. The odd fight outside was enough to get it closed

and a determined council veto every time it reapplied for its licence. As in

most towns, of course, this was nothing compared with what used to ferment in

the trainee Nazi taxi queues every Saturday night. 3D remembers making a regular

detour round the fringes of the city centre to avoid a potential pasting. This

writer's chief memories of venturing up to the youth club at Barton Hill estate

in 1977 to see Siouxsie And The Banshees or Adam And The Ants (for 50p!) are

of the ever-present menace and the fact that it all kicked off on a regular

basis. "What do you thnk it was like for me?" savs G.

"I was never

down with punk," says Mushroom when I relay the same tale to him. Growing

up in St. George, midway between St. PauPs and Barton Hill, punk has a whole

other resonance for Mushroom: more Oi! and Ain't No Black In The Union Jack

than Agitprop and Rock Against Racism. "Punks and psychobillies and skinheads

were pretty much the same thing to me," he says. And in such statements

you get a sense that the roots of the rift that developed in the band during

the making of Mezzanine were as much ideological as aesthetic.

3D reels off for me a typical

dysfunctional youth's CV. Couldn't get into art school, kicked out of sixth

form, did Thatcher's Youth Opportunities Programme, got community service for

painting on walls. "But not tagging," he emphasises. "Writing

your name on a wall anywhere you can, without any artistic intent, seemed pointless

to me. Some kids slagged me off for moving away from the traditional spray paint

thing and onto canvas. I was like, look mate, been there, done that. I'd spend

four or five hours in front of a brick wall painting all night and all these

fuckers do is turn up with a marker pen and tag over everv available surface."

He met Goldie around

this time and formed an art project called The Transatlantic Federation. "Although

all we ever did was this exhibition in Birmingham," he laughs. "We

had business cards and everything." Always hustling for his spot back then,

trying to blag a niche. It's a collective sense of quest you get from all three

of them when they talk about their formative years. "Mind you, I tried

doing some paintings for the new album sleeve," 3D adds, "but they

were bollocks. I'd put no groundwork into it. No preparation. I went into my

workshop over Christmas but it was freezing cold. The paints were iced up and

I had to wear gloves. Pure misery. Breathing in aerosol fumes when I should

have been having a glass of Bailey's under the Christmas tree."

3D is the band's motormouth.

He talks in rapid staccato bursts, but he is frequently the most self-deprecating

of the three, even sending himself up when he talks about his punk epiphany

"It was the teen angst thing wasn't it? Running away from home for three

days. Staying overnight in me mate's squat when I had a bed to go home to round

the corner. Turning up with a packed lunch. I've always had this terrible mix

of bravado and fear which gets me in trouble all the time. I was a bit of a

rebel without a clue then. Nights I spent up in my room with Still Little Fingers

and Clash records shouting at the wall. Nothing meant anything. With hip hop

and The Wild Bunch we were old enough to know better. Putting on the parties

and jams was mad, but even that was a bit sycophantic at first, watching Wild

Style and checking the moves in Buffalo Girls, and there was a bit of objection

from some of the older musicians at first that we were fucking the live scene

up. But after a while Bristol's hybrid identity came through."

"Bristol was always

on the verge of explosion says G, "and it should have happened before Massive

Attack. There was always that potential. You had all the London kids like Andrea

(Oliver) and Neneh (Cherry) coming down, so Bristol became like an extension

of London W10/W11, 120 miles away. All of us in the band come from the same

stem, but we've all branched out. We all tried to have a common goal at the

beginning but it was always coming from different satellite points. It's only

the fact that we were getting on well on the first two albums that it seemed

like it was coming from one thing. But with this album we didn't get on at all

well in the studio. More of the tracks were individually motivated."

As sonic explorers,

as music obsessives, there are as many things that unite Massive Attack as divide

them, but they do clearly have their differences as individuals. Certain aspects

of their personalities gel, some don't. This can of course make for creativity

heaven. It can also be hell. Some of these tensions obviously resolve themselves

in the making of Massive Attack's music (perhaps such tensions are integral

to the creative dynamics of the band). Other conflicts clearly remain unresolved.

They have many imitators but there's no other English band quite like them.

"Nick from anything and make a nice little collage. The Tarantino method,"

G expounds. "But you still have to have vision and imagination."

Not surprisingly he

holds particular contempt for the trip-hop tag. "When vou hear some of

the bollocks that has been made in the name of trip-hop you just want to move

as far away from that as possible. It's just embarrassing." Adds 3D: "Some

guy came up to us in Spain, and said I really loved your show but I think Morchecba

are better. What can you say?"

It was 3D who was

keen to push punk onto Massive Attack. "I was really keen to get in some

of the New Wave stuff," he says. "I feel we'd really missed out on

using that influence. Everybody working in Bristol now has some connection to

that period. I remember fucking about with Lunatic Fringe, a punk band in Bristol,

performing Anarchy In The UK in Sefton Park Youth Club where Roni Size was working.

There's a core of that whole punk-reggae connection in Bristol. So for the first

few weeks in the studio I was sampling Gang Of Four's Entertainment!, Wire's

Chairs Missina, The Ruts, 999. Most of it wasn't working but it was a way of

exorcising some demons."

Did the other members

need convincing about the more spiky direction? "I needed some convincing

myself at first," 3D replies. "There were times when I thought I was

going right up my own arse and had lost the plot a bit." Turning to the

tensions in the band, he says, "There was a period where it almost fell

to bits. In Bristol we had all fallen out badly about what direction it should

be going in and it really was looking likely that it wasn't going to happen.

Going down to Cornwall — in shifts, I might add — made it work.

"But I'm never

satisfied. There are three or four tracks on Mezzanine which are still flawed

and they'll never be right. I find it so suqrising that we can be together and

work together and someone says something and it can be the exact opposite of

what you're thinking. Two days in the studio buried in torment and someone says,

'What this needs is this,' and it's the opposite end of the scale to what you

think it needs. Mush says music to him is an escapist thing. I find it the opposite."

Deep is the word most people

use when they come into contact with Mushroom. Massive Attack's beat architect

emits a quiet intensity which is utterly disarmed by a soft West Country accent

that suggests a wide-eyed innocent. He's rarely anything of the kind. He is

scalpel-precise in his purpose and inquisitiveness.

His voice barely audible above the hotel lobby ambience, he tells me that he

has brought just two CDs with him on tour: A Tribe Called Quest's Beats, Rhymes,

And Love and Pink Eloyd's Dark Side The Moon. He evokes the same '70s/'80s time

frame as frequently as the rest of the band, but for more tangential reasons.

"We seem to have reached a saturation point now, but in the '70s and '80s

people were really exploring new formats, whether it was electronics or in images.

I look back on a lot of those albums and think, Wow. Things like Tubular Bells."

Now, I expected to be exploring several topics with Mushroom, but Mike Oldfield

wasn't one of them. We chew the cud over everything from Morricone to the new

hip hop underground, but Mush can seemingly extract the nutrients from the most

unlikely sound sources. When he cites Tubular Bells he obviously isn't paying

homage to some preserved-in-aspic rock tradition — Manor Studio house-hippy

makes Virgin boss rich — but is hearing something fresh, something that,

liberated from context, can still be worked with. Whisper it quietly, but this

is the wav that music moves forward.

The surprise element in so many of their lineage equations is in many ways Massive

Attack's greatest strength. And so we sit chatting about Oldfield, his exegesis

trip and The Exorcist soundtrack. Seemingly aware of the apparent anachronism,

and obviously wary of journalists, he stops a couple of times, needing reassurance

that this isn't going to be a stitch-up. "Most interviewers roll up like

there's this journalistic vending machine outside," he savs dismissively.

"You put a couple of quid in and pull out a quote." I recommend Oldfield's

Harvest Ridge to him and we move on. As for the Dark Side The Moon connection,

I wrongly assume it's for its sampling potential. Dave Gilmour's bell tolling

Stratocaster, perhaps? The incidental voices? The ambience? Wrong. "I wouldn't

want to sample them," says Mushroom, seemingly unaware that anyone ever

has. "To me they're hip hop, repetitive loops with a simple melody.

"We played in Cambridge," he continues, "and me and Mike, the

keyboard player, walked to Grantchester Meadows. There were 70 or 80 students

out there having barbecues and water-pistol fights and falling into the river.

It was a bit perverse. You got the feeling that this was 'the other side'. All

these people are going to become nuclear physicists or civil servants. All the

future seeds of the empire, getting pissed and throwing beer around, and Dark

Side Of The Moon is all about that. I'm not trying to dissect the album, I'm

just trying to see the method in it."

Melankolic is both the name of Massive Attacks record label and a defining mood

that underpins much of their work. 3D talks passionately about his Anglo-Italian

roots, about the melancholy in the old Neapolitan love songs. "But they

don't make you sad," he stresses. "People say our albums are dark

and melancholic, but I say its like Radiohead's OK Computer. It's quite tragic

in places but you don't leave the album feeling tragic. You feel enlightened.

But even as a kid with Abbey Road or Roxy Music, I was always into the most

melancholic tracks, like I Want You/She's So Heavy or In Every Dream Home A

Heartache. Even with punk. Tlable Talk on Dirk Wears White Sox."

Talking with Mushroom I pursue a different take on the same subject. There's

a vibe line that runs from the earliest, grittiest R&B to that yearning

you can hear in Unfinished Sympathy. Even in the most burning disco track there's

that aching emptiness, that feeling that at the end of a sweaty, hedonistic

night you can still go home alone. "That's the soul," says Mushroom,

and he isn't talking about mannered sock-it-to-me-isms. It runs deeper with

Mushroom. Evervth ing does. He tells me about the problems they had when they

sampled Our Day Will Come from Isaac Haves's To Re Continued for Exchange on

the new album. "That was always one of the records I used to cut up with

The Wild Bunch, so I had the label blacked out 'cos I didn't want biters to

know what it was. We had to do a bit of research to see who the publisher was.

Both the writers are dead now but the wife of one of them said we couldn't use

it. Luckily I'd sampled a bit that Isaac Hayes had written into the outro."

Massive Attack have

always looked outside the core trio for musical collaborations with kindred

spirits, not just in old grooves but also in the flesh. Former Cocteau Twin

Elizabeth Frazer was one: now living in Bristol, she'd previously been sounded

out before Protection but hadn't responded. Did she say why? "Have you

met Liz?" 3D splutters with laughter. "She's very excitable and quite

mad in the best way. She threw a million words into the air and we tried to

grab a few and work out what she meant. Me and Mush met her in Sainsbury's and

invited her up to the studio. There was this nerve-wracking moment before she

arrived and I said. It's really sterile in here, let's light some candle in

here and make it funky for her. She loved our Siouxsie And The Banshees sample

on Metal Postcard — she'd just had this Siouxsie And The Banshees tattoo

removed from her arm. We didn't use that track but she's really cool. Her voice

is so immense and ethereal.

I tell 3D that Inertia

Creeps, one of the highlights of the stage show, is reminiscent of the title

track off Public Image's Flowers Of Romance. "'UK beats came from Istanbul,"

he says. "We went to a belly dancer show on our day off in this really

tacky tourist club. It was a cabaret thing; this guy did a version of New York,

New York with his cane and hat. Then the belly dancers came on and they'd all

seen better days. It really was han ing but the music was wicked. Mush went

and got some tapes the next day." The PiL connection runs deeper than that,

he adds. "We tried working with Wobble on Protection, but it didn't work

out. He's quite a stubborn bloke and we've got that mentality as well..."

Given the angst etched into

Meazzanines tracks, will there be another Massive Attack album? "Hopefully

We've been immersed in music for 15 years. There's still lots ot reference points

we can draw on," says Daddy G, with all the hope and trepidation of a peace-keeping

force.

3D is more pensive

and circumspect. "As people we were in a com-pletely grey area when we

were making Mezzanine. None of us knew what the other wanted, and maybe we didn't

care either, which is even more destructive. It could be the end, for all I

know, but this is definitely a transitional period; we've got a lot to sort

out. Touring is a great escape and we don't have to deal with each other's problems,

but sooner or later we have to resolve things. That could be the end or the

start of something new. But I don't know if any of us have got the bottle to

go it alone. We're too insecure. It's Inertia Creeps all over again, isn't it?"

"I wonder if

we've reached saturation point now," says Mushroom about music in general.

"We've reached all the frontiers. There was the acoustic frontier, then

electronics changed music completely. But what's next." We^ve only got

so many toys to play with."