Massive Attack's New Studio

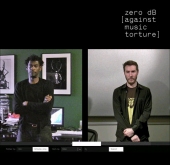

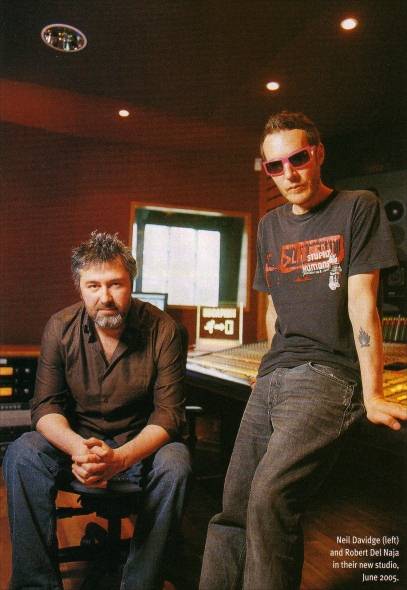

Robert Del Naja • Neil Davidge

Production pioneers Massive Attack are going through exciting times; they've built an awesome recording studio, they've moved into surround soundtrack work, and there's a new album on the way. We take a look around their new workspace.

With the proliferation of low-cost recording equipment on the market, it's not surprising so many artists have set up private project studios. Indeed, there's a long tradition of bands investing money in their own equipment, both to defray future recording costs and to provide a creative environment that they can use whenever they want.

However, there's a world of difference between a small project studio designed for writing and pre-production, and a full-blown 5.1-capable recording facility that can be used to record and mix an entire album or film music project. If you're going to put something like that together, you have to be pretty sure of your finances, and see the investment as a long-term career strategy that fits in with the way you want to record.

This perfectly describes what Bristol band Massive Attack have done. With four internationally successful studio albums to their credit — all of which have been hailed as groundbreaking in terms of creative content and technical aspirations — the band are undoubtedly financially secure enough to consider such a brave move. And they'd certainly outgrown their project studio — a couple of programming suites at Christchurch Studios, Bristol.

A Place Of Our Own

"I've been pushing the band to make a decision about having a proper studio for some time," says Neil Davidge, who co-wrote and co-produced the last two Massive Attack albums, Mezzanine and 100th Window. "If music is your career and what you put your life into, then there comes a point when you've got to put roots down and really make a commitment to the way you want to work. But even for Massive Attack, where it makes absolute economic and creative sense to have our own studio, it still took nearly six years to get from talking about it to building it."

The new facility Davidge refers to is bound to be called the Massive Attack studio, although it actually belongs personally to Davidge and Robert Del Naja, the creative force behind Massive Attack. Nevertheless, it's where most of the work will now be done on Massive's future projects, because Del Naja has chosen to make it his base. "This is something we've always wanted" he says.

" When the band was first formed, our two aims were to get our own studio and our own label, and in an idealistic way, become self-sufficient. The label idea went by the wayside, but my relationship with Neil has made the studio a reality, and I'm really excited by the creative possibilities it opens up for us.

"We wanted to get out of the cycle of hiring studios to make albums, and then promoting and touring them because there isn't much flexibility in that" continues Del Naja. "Creativity isn't something you can easily define because it comes and goes in a very random way. I've lost track of the number of times I've gone on writing weekends or holidays and done nothing, only to find myself facing a really busy time but unable to sleep because I've got so many ideas in my head. That's the perverse nature of creativity, but having our own studio gives us an outlet for it, because we can come in here and use it whenever we want.

"Massive Attack is very much a communal group and doesn't operate like a traditional band. We've always incorporated lots of different people, different ideas and different equipment. Now we have the scope to extend that philosophy — one day we could be working with a film director, the next a new drummer. It doesn't matter, as long as they bring something new to what we do. I've always worked best when I'm multitasking. My mind does wander from place to place, so it's good if there are lots of different things going on. This contrasts nicely to how Neil is, because he's much better at dedicating himself to something and immersing himself in it. The differences between us make for a great working relationship because he brings concentration to some of my wilder ideas."

"I had my own personal reasons for wanting to build a studio, but from the band's point of view it always made sense, because of the way in which they record," explains Neil Davidge. "With Massive Attack, it's not about sitting down with an acoustic guitar or piano, writing a song, going into a studio, recording it and then mixing it. That's just not how we work. What we tend to do is build the sound up in layers, which can be a much more convoluted process.

"We usually start with a few basic ideas — perhaps some rhythm patterns or a keyboard part or a bit of guitar — then we build on that melodically and sonically until we have created something we're all happy with. This means that the various processes of writing, recording and mixing become the same. There are no boundaries — or at least if there are, they become incredibly blurred. Take Mezzanine, for example; with that album we were literally re-writing songs while we were mixing it. The track 'Angel', for instance, ended up as a completely different song because when we pulled it up to mix it at Olympic Studios in London, we decided that we wanted to bring in an extra bass line and change the rhythm patterns, just to see what it would sound like. It sounded great — but it certainly wasn't the same song any more, much to the confusion of poor old Spike Stent, who was mixing with us. He kept shaking his head and saying 'well, now I've seen it all — I just don't know what to expect with you guys!'."

The

beautiful live room, currently home to a Mk I Fender Rhodes Stage Piano

and a Premier drum kit.

The

beautiful live room, currently home to a Mk I Fender Rhodes Stage Piano

and a Premier drum kit.The new studio has a live area with a separate overdub booth, which is big enough to record a chamber ensemble but too small for full orchestral strings. Davidge says he doesn't mind, as he's happy to go to London if that's what a project demands.

"There are some great musicians down here in the South West and, where possible, we do try to keep things local. But for orchestral input you have to go to London, because the musicians there are just incredible," he says.

So if strings will be recorded in London and vocals in the control room, what will the live room be used for?

"Drums," says Davidge. "And guitars — that kind of thing. Although a big live room is what you need for those big drum sounds, we generally prefer drums to be fairly dry, so we can mess around with various effects afterwards. If we'd had a big live room, we'd probably have screened bits off, so we're better off with what we have.

What we wanted to create was a recording space in which to experiment. Personally, I'm not one of those people who likes to say, 'OK, what's the tried and trusted way of recording this Instrument? What's in the manual?' I want to be able to stick microphones everywhere, listen to them and see which ones sound interesting. I want to wheel In odd things like tubing and say 'let's try miking the drum kit through this'. I've actually done that and It was bizarre. It sounded like everything was flanged; an amazing sound.

"At some point, I'm going to have a drum kit In our live room and mike it up all round the building just to see what happens. I'll probably have to do it at night when the road outside is quiet and no one else is around, but I will do it because I want to see how it sounds. It's that potential for experimentation that I've always wanted. We didn't have the space at the old studio and if we went elsewhere, we were up against time constraints and budgets."

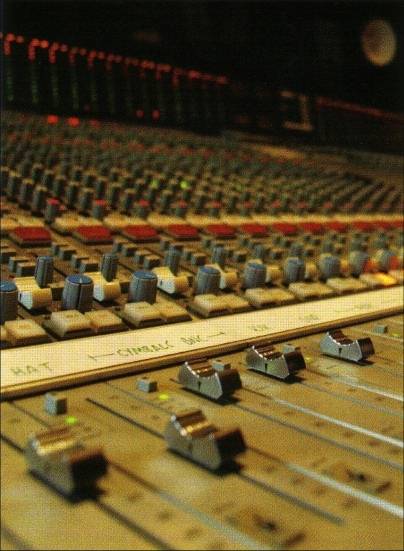

The control room is small (in accordance with Neil Davidge's wishes) but stylish, is centred around the SSL 4000G+ desk, and has a range of monitoring options, from the desktop multimedia speakers and adjacent industry-standard Yamaha NSios on the meterbridge, up to the vast Dynaudio MZ)S mounted in the walls.

Remake, Remodel

The new studio, located on a small industrial estate, took some finding. "We went through various options," says Davidge, "places out in the country, big old barns, that kind of thing, but always within the Bristol area, because this is where we all want to stay. Eventually, after about four years of fruitless searching, we found this place. An industrial estate wasn't exactly what we'd had in mind, but when we saw the space we were being offered, and realised its potential, we decided to go with it."

" Initially, buildings like this were our last choice," admits Del Naja. "But reality crept in, especially as we got towards our lease deadline at our other studio, and we realised that this was going to save us a lot of hassle and planning problems."

The building was already being run as a rehearsal studio and although it was a nightmare of 1970s decoration and in need of a complete overhaul, it did have the bones of a recording area and control room in place. Davidge chose studio-design company Munro Acoustics to handle the refit. "The live room and control room were already in place, so there wasn't too much to change" says Del Naja. "The Munro guys came in and looked at the floor plans, but as the two main rooms were already purpose-built floating rooms, we didn't have to spend any money putting them in. It was simply a case of maximising the audio quality."

The acoustic remodelling was handled by Munro's project managers Phil Pyatt and Andy Lewis. Del Naja: "Munro were given certain criteria regarding the acoustics because we didn't want a live-sounding control room, we wanted it to sound fairly dead." Neil Davidge explains why: "I didn't want the room to sound too live, because I like to record vocals in the control room, so creating a feeling of intimacy was important. I don't like big control rooms anyway; I prefer to have everything within easy reach. The control room was already the right size, so there was no need to change it, although we created a machine room and installed a proper line of sight between the control room and the new live area. We also built a decent reception area, and there are now a couple of programming suites downstairs. We haven't started developing the upstairs yet, but we'll eventually put in a kitchen and lounge so that there's somewhere to relax. It's not uncommon for us to spend 16 hours a day in the studio, so we're very keen to make this a pleasant place to be — and not just for us, but also for the artists we work with."

Gear Heaven

In terms of equipment, the studio features everything that was already in place at Christchurch, plus a number of new additions, including a large console and a 5.1 monitoring system for film soundtrack work, of which more later. The success of Mezzanine and 100th Window/has given Davidge the financial freedom to significantly add to his instrument and equipment list, and he regards it unashamedly as an investment. "The tools of my trade are computers, keyboards, guitars, compressors, and so on, and I've always believed in investing back into my own business. I'm always buying equipment magazines and reading reviews to see what's new on the market."

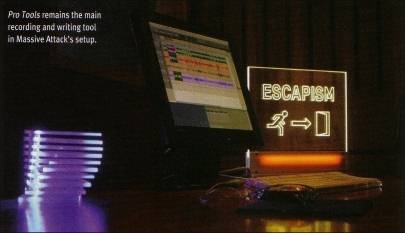

Digidesign's Pro Tools is still the main recording tool of choice, and since the recording of 100th Window, it has been the main Massive Attack writing medium, too — during that project, they completely abandoned their older hardware samplers and software sequencers, recording everything in Pro Tools as audio.

On the hardware side, recent additions include a Manley EQ, Fairman and Teletronics LA2A compressors, and a Focusrite Liquid Channel. Davidge has also acquired some BLUE and Coles mics, and a couple of guitars. However, the biggest single investment for the new facility was the SSL console, which came from Roundhouse Studios. Del Naja explains: "For the last 10 years, we've been working on an SSL at Olympic, so it's a console we understand and can relate to. Also, we're keen to get [SSL fan] Spike Stent into our studio when the time comes to mix, because he's been a co-collaborator on our albums for a long time. Having a desk he knows and likes will make that much easier."

" It's a G Plus with all the bells, whistles and go-faster stripes," Davidge says. "There's a lot of flexibility with SSL; you can get them to sound really crusty and really warm. Our desk is a good workhorse that does everything we need it to do. We wanted a big console — something that the band could sit in front of, where they could play around with individual faders. Also, we wanted a console that was primarily a recording desk, regardless of whether we're working with Pro Tools or a tape machine. It's not something I will personally drive, as it's Lee's toy [Lee Shepherd, engineer and Davidge's right-hand man]. He's our SSL expert." And not just that, as Del Naja explains. "Lee is a whizz at everything to do with studios and equipment. He's remarkable. He can take the whole studio apart and put it back together again, which is why he's so vital to the success of this place!"

Shepherd also chose the main monitors, Dynaudio M4s. "We were using Genelec 1032As as our main monitors, but they weren't big enough for the new room," Davidge explains. "We checked out various systems and eventually chose the M4s. Main monitors are great for vibe, and there are times when you have to turn them up loud, but mostly I prefer to listen to them quietly. Playing them at full volume allows you to judge interaction and hear resonant frequencies, but there's no need to make your ears bleed. You can sense power from a track by the interaction of the sonics; you don't need volume. If you can't judge properly at low volumes, you're doing something wrong."

For nearfield work, Davidge has his Genelecs and a pair of ubiquitous Yamaha NS1 Os. He also likes playing with cheap and cheerful computer speakers so that he can tell how the track might sound when his audience plays it at home. "When you're in the studio it's very difficult to judge what your track will sound like on any old system. Our approach is to stem the mix down into eight tracks of stereo, then put that through cheap computer speakers and listen to what's happening. Is the snare drum in front of the vocal? Is the guitar solo drowning everything out? You get a feel for the overall perspective, which is important when you're mixing, because if you record a great vocal and then mix it down by as little as half a decibel too much, you can end up clouding the song. Half a decibel may not sound much, but it's enough to make all the difference to the intelligibility. Keeping a sense of perspective like this is especially important when you've been working on a track for a long time, and have got to the stage where you know every single note, every single sound, every single bit of crackle and buzz. At that point, trying to put yourself into the headspace of the person who is listening for the first time is very, very difficult."

As you would expect, the studio contains some of the finest

processors in the world, including an SPL Transient Designer, two Empirical

Labs Distressors, an

Audio & Design Fy6oXRS compressor/limiter/expander, a Focusrite Platinum

Compounder, a Drawmer LX20 dual expander/compressor and two DS201 dual gates,

Fairman and Smart Research C2 compressors, a Mutronics Mutator filter bank, an

Electrix Filter Factory, a Teletronix LA2A compressor, a Massenburg Model 8000

EQ, a Tubetech LCA2B compressor, a Drawmer 1960 valve compressor/preamp, a Focusrite

Red 7 mic preamp/dynamics processor, and a joemeek stereo compressor.

As you would expect, the studio contains some of the finest

processors in the world, including an SPL Transient Designer, two Empirical

Labs Distressors, an

Audio & Design Fy6oXRS compressor/limiter/expander, a Focusrite Platinum

Compounder, a Drawmer LX20 dual expander/compressor and two DS201 dual gates,

Fairman and Smart Research C2 compressors, a Mutronics Mutator filter bank, an

Electrix Filter Factory, a Teletronix LA2A compressor, a Massenburg Model 8000

EQ, a Tubetech LCA2B compressor, a Drawmer 1960 valve compressor/preamp, a Focusrite

Red 7 mic preamp/dynamics processor, and a joemeek stereo compressor.

There's

a more curious mix of budget and high-end in this rack, including Manley,

Neve, Avalon and Focusrite EQs and voice channels (including the

new Liquid Channel and Voicemaster Pro), and Zoom Studio effects, two Electrix

MOFXs, a Line 6 Echoplex, and an old Alesis Quadraverb!

There's

a more curious mix of budget and high-end in this rack, including Manley,

Neve, Avalon and Focusrite EQs and voice channels (including the

new Liquid Channel and Voicemaster Pro), and Zoom Studio effects, two Electrix

MOFXs, a Line 6 Echoplex, and an old Alesis Quadraverb!

Cutting Remarks

Whether he's working

on a film score or an album track, Del Naja believes the most important part

of the creative process Is editing.

"That Is what defines everything. You can have loads of great ideas and

be sketching different sounds in the studio, but unless you put them into

order and context, your work won't have any meaning for anyone else. Editing

is creative

in its own way, because It's where you choose what

people will hear.

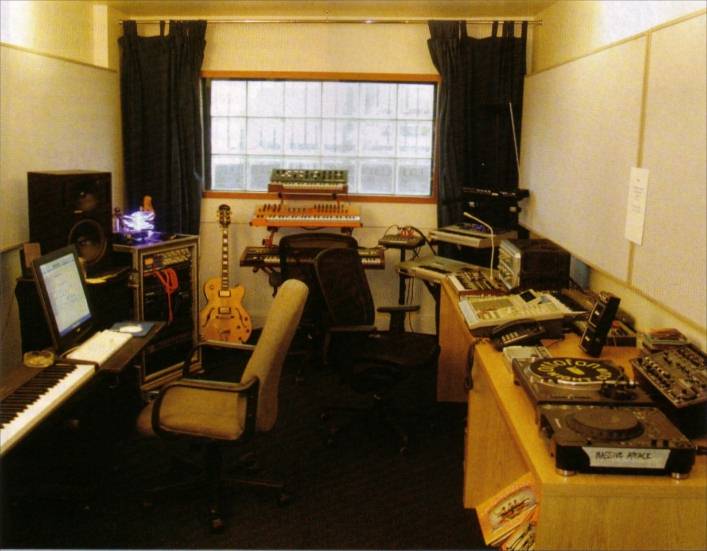

One

of the programming suites at the new facility is itself a dream project

studio, with a treasure trove of fantastic kit. The keyboards at the far

end are a Moog Prodigy, a Waldorf Microwave XT, and a Roland )uno 60, while

off to the right there's a Noiderland Stereo Theremin, an Access Virus

Indigo 2, and a Korg Triton. There are more rackmount synths and sound

sources next to the guitars on the left, including an Oberheim Matrix woo,

Novation Drumstation, Roland MKS/o and JVloSo, with a Focusrite ISA430

channel strip. The worksurface on the right seems more dedicated to rhythm

creation, with a Korg Microkorg synth, Electrix Filter Factory and MOFX

processors, an Akai MPC3000 sampling workstation and a Roland SHwi monosynth,

a Korg Electribe RX rhythm box and two Kaoss Pad controllers (an original

and a Mkll model). Finally, there's a Technics vinyl deck, a Pioneer CD

turntable, and a Numark D) mixer. A selection of vinyl can just be seen

under the table, with the Residents and the Beatles to the fore! Just out

of shot by the master keyboard and Pro Tools rig on the left of the room

is a large screen for use in Davidge

and

Del Naja's music-for-picture work.

One

of the programming suites at the new facility is itself a dream project

studio, with a treasure trove of fantastic kit. The keyboards at the far

end are a Moog Prodigy, a Waldorf Microwave XT, and a Roland )uno 60, while

off to the right there's a Noiderland Stereo Theremin, an Access Virus

Indigo 2, and a Korg Triton. There are more rackmount synths and sound

sources next to the guitars on the left, including an Oberheim Matrix woo,

Novation Drumstation, Roland MKS/o and JVloSo, with a Focusrite ISA430

channel strip. The worksurface on the right seems more dedicated to rhythm

creation, with a Korg Microkorg synth, Electrix Filter Factory and MOFX

processors, an Akai MPC3000 sampling workstation and a Roland SHwi monosynth,

a Korg Electribe RX rhythm box and two Kaoss Pad controllers (an original

and a Mkll model). Finally, there's a Technics vinyl deck, a Pioneer CD

turntable, and a Numark D) mixer. A selection of vinyl can just be seen

under the table, with the Residents and the Beatles to the fore! Just out

of shot by the master keyboard and Pro Tools rig on the left of the room

is a large screen for use in Davidge

and

Del Naja's music-for-picture work.

From Sound To Pictures

The writing and production

collaboration between Neil Davidge and Robert Del Naja is now well established,

having spawned two albums and, most recently, a host of film music including

the soundtrack for Luc Besson's movie Unleashed. Given that both Davidge

and Del Naja come from art backgrounds (Davidge was once a graphic designer

and

Del Naja is both an artist and a musician), it's no surprise that the pair

have embraced

film music to such a large extent. " From the start, our music has been

used in film, and we've been part of the film process through our videos," says

Del Naja. "It was inevitable

that we would get involved with film scores. As a lyricist, you absorb ideas

from TV and film — you can't

help it. With film scores, it's more a case of noticing how an atmosphere

works in a film, and how the music fits in. This

is something we always

wanted to do."

"It has always interested us, because we do have a very visual approach

to music," agrees Davidge. "Although

the Unleashed soundtrack is the most intensive project we've done so far,

we didn't come at that from a standing start, as

we'd already completed tracks for a Robert

De Niro film and written music for the Day Of

The Jackal remake."

Davidge

adds that writing for the big screen is more than just creatively satisfying —

it's also the perfect complement to album recording, which he admits can be

quite stressful at times. "The problem

with making albums is that there's huge pressure on you to keep re-inventing

yourself, and that's really, really hard.

Also, it's not uncommon for us to take a year

or more to make an album, which is a long time

when compared to most other bands, and you do

get into a weird place mentally when you're involved

with an album project that's been going

on for so long. So we're always trying to

find ways to break out of that, and film

work is a great way to do it. You're working

on someone else's, project and vision, which is

incredibly liberating. Who, for instance, would

think of Massive Attack doing a ballad? You just wouldn't

expect that on one of our albums,

but with film, we have that flexibility."

Del

Naja echoes this, and adds that writing for film is a very different process,

because it is linked to a visual,

which gives you a guide as to what works

and what doesn't. "You

know how far you can take the music, and what's absolutely wrong and incongruous.

This isn't the case with album tracks,

because there the process involves instruments,

lyrics and an inevitable amount

ofrandomness, so you're not sure for a long time

if you're achieving what you set out to achieve.

And often a track will move in

a totally different direction, because you have

no parameters set in advance. Sometimes

you get a perfect moment when you have a

simple song, a simple idea, and it's beautiful;

you know you hardly have to touch it. But more

often, there's a lot of messing around

and experimenting before you get

to where you

want to be. With film, you are also

part of someone else's project — you're

not in control of it, and that's quite nice, in a way. You don't lose sleep

over it, because you're not so emotionally

attached, and so you try things you wouldn't normally

do."

The Unleashed

soundtrack album, which was released by Virgin at the end of last year under

the title Danny

The Dog (after the name of the film's main

character) features 21 Massive Attack

tracks from a total of more than 50 that were created

for the movie. Davidge says: "We were

given a finished cut of the film and were told to do what we wanted. The result

is

wall-to-wall music—about

90 minutes of it — which

we did in just over three months. Most of it was written from scratch. And

we were doing that while trying to build a studio

and write new material for our next album, so you

can imagine the kind of hours we were putting

in!" As

the new studio wasn't ready at this point, the bulk of the soundtrack was

recorded at Christchurch using the band's own

Pro Tools setup. Strings were recorded

at Angel in London and the whole lot was eventually

delivered to director Louis Leterrier for

inspection.

"Louis was great — a joy to work with," Davidge says. "He

would explain the scenes and give us some idea of what he wanted, but he

was very respectful of what we'd done in the past and gave

us creative freedom. We both sat in our room

playing piano, looking up beats and coming up with

some bizarre effects that we collected

together as a lot of rough sketches. We gave

them to Louis who took them away to see

what fitted. He cut some of the music to

a few scenes to show how he thought certain tracks

might work. It was a great way of working,

because we'd seen the film and had an

overview of what it was all about without getting

too specific in the

studio. It was more a case of what each scene made us feel, musically."Leterrier

made it clear that the music was to be the film's focal point. He wanted it mixed

at high

volume levels and, crucially, he didn't want the volume turned down for the

dialogue. This

meant careful attention to the arrangement. If

something in the frequency range clashed with the dialogue,

then Davidge and Del Naja had

to change it. "It

was incredibly difficult and challenging, but I think we achieved what he wanted," Davidge

comments.

A 5.1 mix

was created at Luc Besson's film studios in Normandy with the help of sound

designer Vincent

Tulli. " Louis

wanted the surround effect to be quite extreme, not just a bit of reverb panning

around at the back," says

Davidge. "He wanted the sound everywhere,

so that the whole thing became an experience. This meant that we went to

town with 5.1, which was fun for

us because it was the first time we'd

really played with it. We had Vincent

in the studio with us and his experience

was invaluable. Lee would

mix the track and get it to a certain stage, then

Vincent would come in and

start panning sounds around to see what

worked. Most of this was done using

the automation within Pro Tools and involved

quick movements that were quite

frenetic. Very few people have used

5.1 in such an extreme way on a film.

There were one or twooccasions when

Vincent went too far and it started

to sound annoying, but overall we

loved the effect, and we learned

a lot from the experience."

Unleashed

was followed by another film project — a British film called Bullet Boy.

This helped consolidate Davidge and Del Naja's 5.1 expertise, and they now

feel very

confident with the format. "The

best approach is to mix the music in quad, which is very easy to do from stems," explains

Davidge. "You

can also derive a sub channel from this, and leave the centre channel free

for dialogue. It's onlywhen you

have music and no dialogue that you need to use the centre

channel, usually for a lead instrument or a

specific sound effect. Once we've put down

our stems and worked out our 5.1, we hire

out a small Pro Tools rig to the film company

for the final mix. If they want to

push the 5.1, they can, but if they want to

tone it down, they also have that option. We

give them all the stems, so if there's a single

instrument getting in the way, they can

change it — it

gives them a lot more control. We don't shirk our responsibilities for

getting it right, but we do leave enough room

for the client to make the adjustments that suit them."

What Next For Massive Attack?

Since opening the new studio at the beginning of this year, Davidge and Del

Naja have been focusing on film scores, having formalised their working relationship

by setting up a music production

company, 100 Suns. And a new Massive Attack

album is in the works, currently planned

for release in 2006. Del Naja has already

recorded a few rough tracks, and they

also have material from Grant Marshall, who took

time out from Massive Attack while the

band recorded 100th Window to fulfil personal

commitments. He's back now and fully involved,

which they're all delighted about.

Davidge

says: "We have a lot of sketches — about

40 so far, some of which were archived from previous projects but are worth

re-working. There's always cross-fertilisation going on and we do tend

to file things. We may be working on a remix for someone

when we come across a sound

that's so great we'll put it aside and keep it

for the next album. Also, while we've

been working on film material, we've

come up with ideas that are better as album tracks.

Lee is our archivist and keeps everything,

because we have great memories for those

gems we didn't find a home for at the time.

It might just be a sound or a rhythm pattern,

but we'll remember it, and then get Lee to

find it. He has a hell of a job, especially

when we haven't given it a name!"

Inevitably,

the construction of the studio and the 100 Suns film work has slowed progress

on the new album. "This

year has been about making progress with 100 Suns and establishing ourselves

with the film industry," says Del Naja. "We've

had to build trust with these people, because if they are going to commit to

us, they need to know we won't let them — or

their deadlines — down." However, the

film work has also influenced the new album in positive ways, inspiring a couple

of potential tracks, as Davidge has already mentioned, and

giving the creative process a different

emphasis. "In

the past, we've written instrumental parts first and fitted songs around them," says

Davidge, "but this time, we're using the film-score approach, putting

down quick sketches so that we get basic chord structures going — melodies,

riffs and so on — to give us

an idea of how the backing track might sound. In theory, this should make the

process a lot quicker, and enable us to keep

everything feeling fresh. It might also

stop us becoming so bored with a track that we

end up changing it at the mix!"

Previous Massive Attack albums have seen vocal collaborations with carefully

chosen guests such as Tracey Thorn, Tricky, Liz Frasier and Sinead O'Connor.

So who's on the new album?

"We have several possibilities, but I can't say who yet; negotiations

are still at a delicate stage," says

Davidge. " We've sent out rough sketches and hopefully, over the next

month or so, we'll sit down with a few people and see what happens. They may

be surprising from

the point of view of not being

particularly well known. These days, we

can go for what interests us' rather

than what has commercial appeal.

The band has worked with some great

singers in the past, and it's been a highlight

of my career to do that, but

with established singers, the pressure on us is

to find something new within them, and that

can be a distraction from just trying to get something

good. So some people we use may not be well

known for that reason."

As

our interview draws to a close, Del Naja explains that the 100 Suns film work

has positively

influenced Massive Attack's working methods

in this area,

too, providing another potential avenue

for collaboration with vocalists. "100 Suns gives

us the freedom to try different people for different reasons. One of the films

we hope to be doing in the New Year

has an emphasis on soul music, so we're collaborating

with people like Bobbie Womack and Terry

Callier. It would be great to use

Terry on the album as well as the film score.

That's an opportunity that's come about

as a result of 100 Suns and the film projects — without

that, it might not have happened."

Sue Sillitoe