"Are We A Fucking

Punk Band Now?" (Q January 1999)

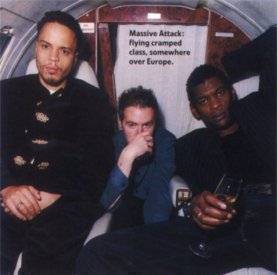

Journo-snubbing, royalty-baiting Massive Attack survived their near-fatal personality

crisis to deliver your album of 1998. David Cavanagh jumps aboard a LearJet

to Oslo, and recounts the story behind the story of that genre-scrambling, trauma-frazzled,

schizoid thing called Mezzanine.

ROBERT DEL NAJA of Massive

Attack is getting his acceptance speeches down to a fine art. In 1996, when

the band won Best Dance Act at the Brits, he dispensed with the whys and wherefores

to announce, "Pretty ironic - none of us can dance". Today, collecting

the Q Best Album trophy, he is just as economical. He thanks the bands manager

and their co-producer, and that's it. He does not remark on the irony, but its

there - indeed, it's audible to the entire room - as the beautiful strains of

Liz Fraser singing Teardrop strike up over the PA. Only the people at Massive's

table, however, understand the significance. Of all the songs to play…

In April, the month that Mezzanine was released, the band embarked on a world

tour. The final stretch is a series of large arena shows in major European cities,

beginning tonight in Stockholm. Two airport-bound limousines are already waiting

outside the Intercontinental, when the band are approached by Danny O'Connor,

a reporter for Radio Ones news service, The Net. O'Connor conducts a brief interview

with Del Naja (3D), Grant Marshall (Daddy G) and Andrew Vowles (Mushroom). It's

well known that the trio fell out badly during the making of Mezzanine; what's

less clear is whether the arguments have now been resolved. O'Connor asks Del

Naja if there will be another Massive album; Del Naja replies evasively, "In

one shape or form, there may be". What about solo projects? Marshall concedes

the possibility, but doesn't say when. O'Connor feels he has enough material

to compose a story for The Net's Ceefax pages.

An hour later, 40,000 feet above sea level, Marshall reclines, quaffing champagne,

his long legs extended into the aisle of a tiny private plane headed for Sweden.

He and Del Naja distribute plates of sandwiches, consumed by all but Vowles,

a vegan whose allergy to dairy products has rendered him able to eat only a

fraction of Earth's food. Del Naja and Marshall, a pair of likeable piss-takers,

work their way through the mini-bottles spirits one by one. Vowles is teetotal.

They answer to "D", "G" and "Mush" respectively,

like a toddler losing his way in the alphabet, or a chord that is impossible

to play.

Their live show, in which they are accompanied by a four-piece band and two

singers, is a coalescence dark hypnotic music and white light. An intense, cerebral

two hour performance, it rivals Radiohead for rock dynamics, taut nerves, implied

drama, miraculous sound throbbing aftershock. Del Naja ostensibly doing little

more than whispering into a mic, is subtle magic in action, the embodiment of

Mezzanine's neurotic pulse buzzing head. Thereby, you might say, hangs a tale.

IN JANUARY 1996, a lot of

equipment started arriving at Christchurch Studios in Bristol. Neil Davidge,

a 1ocal producer-engineer who rented a room there, knew Massive quite well:

he'd worked with them on a rernix of Karmacoma for the Bosnian aid album Help.

Now they were moving in as neighbours.

After two hugely acclaimed albums - Blue Lines (1991) and Protection (1994)

- Massive were changing. The vexed issue was: how can a group styled in hip

hop translate late its music to live performance without exposing it's shortcomings?

Previously, the show had been built around drum beats scratched by one man (Vowles)

from two discs at a turntable. As Massive became a hotter ticket, it was felt

the concerts should sound -and look - more substantial. Their friends Portishead.

part of the same sampling-and-scratching culture, had toured successfully with

guitar, bass and drums. "It would have been unspoken," says Massive's

manager Marc Picken. thinking back. "but there was probably all-element

of, Christ, we should be doing this."

By the time Massive moved into their new studio, they had a guitarist, a bassist

and a keyboard player, and were about to add a drummer. It wasn't a reversal

of policy as such - there had been a degree of live instrumentation on both

their albums - but it certainly raised eyebrows when Del Naja. Marshall and

Vowles fronted a full band on Channel 4s The White Room in February. "We

did a wicked version of Eurochild {from Protection)." Del Naja remembers

fondly, "with fucking excellent grunge guitar." When BMG records commissioned

a track for a compilation to mark the Euro '96 football tournament, Eurochild

was what they got: engineered by Davidge; beefed up with guitar. For the first

time, Massive's augmented live act had dictated the way their records should

sound.

As album sessions got underway

(with Davidge booked until September '96), Vowles and Marshall worked on bass

and drum loops. Del Naja materialised almost a month later, bringing a semi-formed

idea and a pile of new wave records: Gang Of Four. PiL. Wire. Bristol's own

Pop Group. It was the music he'd loved in his early teens. It had edginess,

paranoia and confusion; its atmosphere still crackled 20 years later. His idea

was for Massive to make an album like it. How - he didn't know. "I probably

went in there a bit fucking heavy, a bit pig-headed," he now admits. "I

was sampling loads of ridiculous things which were never going to work, like

Stiff Little Fingers and 999. But I was trying to break the mould."

He found an ally in Marshall, a new wave fan himself, whod grown tired of Massive

being perceived as masters of smooth, polished. Urban soul. Vowles wasn't convinced;

what was so wrong with Protection?

Angelo Bruschini, Massive's guitarist, has a rock background. Formerly in The

Blue Aeroplanes. he's used to a routine whereby songs are written. rehearsed,

demoed and then - and only then - recorded in a studio. However, he spent much

of I 996 playing random notes on guitar for hours on end., being sampled by

Davidge and Del NAJA. who would then use a computer to experiment with the guitars

tone, speed, texture and very "guitar-ness". "We really did take

a lot of liberties." Davidge laughs. "Angelo would come into the studio

after doing a long session the dav before and say Wow that sounds good - what's

that? I'd say. That's you mate."

When September 1996 arrived, the tracks in progress were an ill-fitting jigsaw

of Del Naja's barmy post-punk samples and Vowles's chilled-cut R & B grooves.

Nothing was ready.

The first deadline had come and gone.

ON THE EVE of the Norwegian

cup final. Oslo is joyful. The square opposite Massive's hotel resounds to football

songs and the lobby is a black-and-white striped contraflow of supporters' scarves.

The band members move from the lifts to the door and out towards the bus.

Tonight s concert at the Spektrum Arena illustrates what a year its been: they

played Oslo in April to 1,000 people. Now they've upgraded to a 7,000 capacity

venue, and every ticket is sold.

The recording methods at Christchurch were by early 1997, reaping dividends.

A series of live jams (with full band personnel) had been transferred to hard

disk and edited into loops and the mini-bites, as Massive hunted for newer,

more peculiar sounds. Cutting and pasting on computer, they worked on six songs

a day, two hours at a time, hitting the "save" button whenever they

got bored.

The albums' working tide

was Damaged Goods, an old Gang Of Four tune. As Massive continued to honour

live commitments - Davidge would lose them for weeks at a time - Del Naja would

return to Bristol feeling increasingly damaged himself. He was writing lyrics

about panic attacks, hangovers, morbid thoughts and inexplicable actions. On

tour. he would check into his hotel room and glance back at the door as he walked

to the lifts, wondering what silent terrors awaited him on his return. He found

it difficult to interact with friends in Bristol.

It was now clear to Davidge that Del Naja held the key to the album and must

be understood at all costs. The co-producer says, perfectly serious, "Quite

often he wouldn't actually be able to verbalise what he wanted, so it was a

matter of 4 trying to get inside his head and understand him as a person - all

the things that are going on in his personal life, everything." If Davidge

found this

difficult, guitarist Bruschmi had never experienced anything like it. Here was

Del Naja, frustrated by a sound in his head that he couldn't articulate, miming

an imaginary guitar and going, Ner-ner-ner-ner! Ner-ner-ner-nor! Thus was the

Best Album of 1998 made.

One song had a hissing groove;

a bassline that changed completely halfway through; absurdist lyrics made menacing

by the urgency of their delivery; and a staccato guitar effect that sounded

like the track was hyperventilating. This was Risingson., which Massive decided

to release as a limited edition single, as the album had just blown its' second

deadline. Bruschini recalls, "Most of the songs were still in a blueprint

form six-to-seven months down the line, Nobody new how the hell it was going

to happen - nobody."

Horace Andy the sweet-voiced Jamaican reggae star now in his late forties, has

sung on every Massive album. Del Naja had earmarked him as the ideal vocalist

for a bizarre version of Straight To Hell by The Clash that sampled a Sex Gang

Children record. They cued the track up for him in London's Olympic Studios,

only to discover that Andy, a religious man, was unwilling to sing the word

"hell". There was no way round it. "It was like. Let's fucking

sort this out now," Del Naja snaps. "In the space of four hours we

stripped all the music away, wrote loads of stuff around it, keeping some of

the old melody, putting in Horaces' new melodies, taking the Sex Gang sample

away, halving the tempo and adding new words." This was Angel, the album's

brilliant opening song. One line in particular would set the tone for the music

that followed: "Her eyes... she's on the dark side..."

In July, as Massive debuted

Angel and three other new songs at key festival dates around Europe, Risingson

was released. The joint-strangest single of the year (alongside Paranoid Android),

it charted at Number 11. "They were very, very nervous." Bruschini

confirms. "There was a big sigh of relief when that sold, I think."

With half the album recorded. Massive granted their first UK interview in two

years. The London listings magazine article featured a heated argument between

Del Naja and Vowles over the merits of Puff Daddy. Announcing that he'd grown

out of hip hop. Del Naja managed to antagonise the hip hop-loving Vowles. who

didn't like the implication that his tastes were immature. "The next albums'

gonna take six years." Marshall dead-panned. "In fact, we're splitting

up after it."

They very nearly had.

BACKSTAGE AT THE Spektrum

in Oslo, an amused Vowles is watching Gym And Tonic by Spacedust on MTV. Egged

on by Marshall, he turns the volume right up. attempting to blow the television's

speakers. A reticent character, Vowles is hard to interview; there's one song

on Mezzanine he'd rather not talk about. It's Teardrop. Del Naja, choosing his

words carefully, says, "Me and Mush can't talk about music any more. There's

things we want to say to each other that aren't very nice."

Marshall is less circumspect.

"At the time," he frowns, "it seemed like an act of treachery."

When Neil Davidge picked out a pretty harpsichord melody one April day in 1997,

there was no hint of the drama to come. Vowles, arriving at the studio, asked

him what the tune was. Davidge replied it had just entered his head. Taken by

it, Vowles got him to play it into the computer, whereupon they began adding

sombre piano chords and beats. They gave it the working title No Don't - a back-to-front

way of saying "don't know". It already had the potential to be the

equal of Protection s heart-tugging tide track.

In the three years since Tracey Thorn sang that song, Massive's pool of suitable

(and available) vocalists had changed. Del Naja's one-time partner-in-rap Tricky,

now a solo star was no longer an option; to compensate. Marshall had to increase

his own role considerably The only female singer used on the sessions so far

was a discovery of Picken's, Sarah Jay, who sang Disolved Girl.

Vocalists for other tracks remained up in the air. "You just hear a piece

of music and think so and so would sound good on this." Vowles deliberates.

"It just makes itself apparent to you. It's like deciding what clothes

to wear."

Vowles, whose attachment to No Don't had grown strong, believed it needed a

soul vocalist. Marshall and Del Naja, however, imagined someone entirely different:

Liz Fraser of the Cocteau Twins. They argued over this - bitterly As Faser was

pencilled in for a session in late May, Vowles saw his control over the song

slipping away. Years of simmering tension came to a head. Something happened

that put everybody in a terribly awkward position: one day Massive got a call

from Madonna's management in America saying she adored No Don't and would -

of course, thank you - be delighted to use it. Er... what? Nobody has ever confirmed

Vowles as the sender.

By the time Massive extricated themselves from this embarrassment, relations

between Vowles and the others had deteriorated, but he still had one last card

to play. When Eraser sang her chillingly lovely melody line (on what was now

called Teardrop), it wasn't to the instrumental backing of No Don't, but to

a similar instrumental constructed by Davidge from several other sources. Petulantly,

Vowles had taken his ball home with him.

Now that over a year has passed, Del Naja is diplomatic: "It's difficult

for me to talk about it now, because it's obviously a bone of contention between

us all. But me and G were obviously really unhappy about tlie situation. It

\vas at a point where, after a lot ot meandering, the album was finally starting

to develop. There were seven or eight tracks happening which were really sounding

like they made a lot of sense."

With Angel, Risingson and

now Teardrop in the can, the album had its opening three songs. Fittingly, since

Frasers vocal had given the sessions its greatest boost of energy. Teardrop

would stand out as many listeners' favourite track. "It sounds good now,"

is all Vowles will say of Frasers remarkable performance.

AS THE SESSIONS at Christchurch descended into pettiness ("Are we a fucking

punk band now ?" Vowles is alleged to have shouted at one point) manager

Marc Picken and co-producer Davidge rallied to save the album. A holiday cottage

in Cornwall was hired in September, enabling Del Naja, Bruschini and Sara Jay

to fine-tune ongoing material in the countryside, leaving Christchurch free

for Vow les and Marshall to work - though not at the same time. The thinking

was: as long as the three guys didn't meet they wouldn't fight. Amazingly, it

proved a viable arrangement.

Del Naja's image of the album - an agitated mutant unable to communicate - now

mirrored the bad feeling in the band. He had a title for it: Mezzanine, a floor

between floors: a no man's land; a stuck lift. Returning from Istanbul in July,

he'd brought cassettes of Turkish music which inspired a new track, Inertia

Creeps. Full-throttle and super-percussive, Inertia, along with three other

incomplete pieces - Croup Four. Black Milk and Mezzanine - made up the "big

four", a quartet of shadowy, sinister gatecrashers that marked out the

distance they'd come since Protection.

By late November, activity was intense on three fronts: recording in shifts

at Christchurch and in Cornwall, and mixing at Olympic. Liz Fraser, whose name

it was once again safe to mention, had sung on Black Milk - and this was an

important turnaround, because whilst it sounded as saturnine as any Del Naja

track, it had been created by Vowles and Marshall without him. "I was like,

Fucking great." beams Del Naja. "The album's taking shape without

me having to be there."

Del Naja, taking charge of Group Four, oversaw not one but two Fraser vocals

- sung weeks apart - and had Davidge stitch an epic, near-Zeppelin finale onto

the original frame. As for the title track, it went to a fifth mix at Olympic.

Christmas passed and still they weren't ready. Even at ultimate deadline, arrangements

were being tweaked. They were like the chefs on Ready Steady Cook, frantically

wiping the surface tops and adding the garnish seconds after the gong has sounded.

"Literally, the final mixes were going down and we were saying. No, stop

- try this instead!" remembers Davidge. "That's why I wouldn't say

that any of those tracks are necessarily finished. We just stopped at that particular

point."

ON MONDAY. NOVEMBER 2, 1998, while Massive were awaking in Copenhagen, Danny

O'Connors story ran on Ceefax. It suggested the band had given their "strongest

indication yet" that a split was possible. The Sun found the full transcript

of his interview on The Nets Web site: "sampled" some unrelated quotes

and glued them into an incriminating paragraph; and suddenly Del Naja was "admitting"

Massive were breaking up.

A hastily issued Massive press release rubbished the claim, blaming O'Connors

"cliched" questioning, although it somehow forgot to condemn The Sun's

deceit. In all the fuss. nobody quoted Vowles, who'd said that work on a new

album was likely to commence in early 1999.

Marshall, who has described the recording of Mezzanine as the most traumatic

time of his life, tells Q he has no wish to repeat the experience. In future,

therefore, they will work separately. White Album style, on self-written tracks,

then bring them together. "Being apart will give people the freedom to

work," Del Naja agrees. "I think it'll be a better way."

To put Massive's trials, tribulations and traumas in context, one needs to go

down a couple of floors. While they were making Mezzanine. Bristol rock band

Strangelove, working in Christchurch s studio downstairs, recorded an entire

album, promoted it, toured it - and split up. Massive Attack are still together.

David Cavanagh