A new Massive Attack album is always an event, and this year's 100th Window was perhaps the most eagerly anticipated yet. Like its predecessor Mezzanine, it was co-produced and co-written by Neil Davidge. by Nigel Humberstone

The city of Bristol is synonymous with acts such as Portishead, Kosheen, Roni

Size & Reprazent, Wedding Present and PJ Harvey, but most of all Massive

Attack, a group who have helped redefine dance music. Their I 991 debut album

Blue Lines blended hip-hop, new wave, reggae, early house and techno as well

as giving us the memorable single 'Unfinished Sympathy', The follow-up Protection,

featuring Tracey Thorn and produced by Massive Attack and Nellee Hooper, was

an equal success, cementing their position as a pioneering musical force.

Then came the difficult

third album Mezzanine. By the time they recorded it, the band had crossed paths

with singer/songwriter/remixer and producer Neil Davidge, with whom they had

worked on a number of soundtracks (including Batman Forever) and special project

mixes like the HELP album. The collaboration has since flourished and helped

draw together what was becoming a fragmented working relationship between the

founding band members.

"Mezzanine was

a pretty sketchy album in terms of the way we worked," recalls Neil, "because

the band, as reported a lot at that time, were not getting on. So I'd be in

the studio working

with one of the members and someone else would come in, then the person I had

been working with would leave and I'd have to change the track I was working

on because they didn't want to work on that track, they wanted to work on something

different. Sometimes I'd be working on perhaps four different tracks in one

day, which was a pretty messy way to work."

Mezzanine had shown the band taking a new, guitar-led direction, which established

the writing and production liaison between Neil Davidge and Robert Del Naja,

better know as 3D or simply D. With founding member Andrew 'Mushroom' Vowles'

departure following Mezzanine and Grant 'Daddy Gee' Marshall's current sabbatical,

D has increasingly become the driving force behind Massive Attack.

Neil Davidge in Massive Attack's Christchurch Studio.

"Originally I was going

to be programmer/engineer," recalls Neil, "but we got on so well that

I ended up co-producing the album and co-writing. The only reason Mezzanine

hung together as an album was because the two of us drove it through, and there's

a similar scenario to the new album 100th Window. If there were neither one

of us in the studio then nothing would happen. D has a very unique way of seeing

a project, be it a musical one or visual one, and I've got the ability to turn

what he's talking about into actual musical form, so it's pretty essential that

the two of us are both in the studio."

The fact that Davidge

used to be a graphic designer and D is renowned for his artistic vision within

Massive Attack both musically and with artwork design is another point of reference.

"We communicate in a very similar way — we talk about visuals when

it comes to a piece of music. It's about the picture it makes — it's all

about textures and contrasts and is a very visual language. A lot of more traditional

producers don't necessarily communicate in that way, which I think D has found

difficult in the past. When we started talking about records we loved we just

found that we were talking the same language, which is essential."

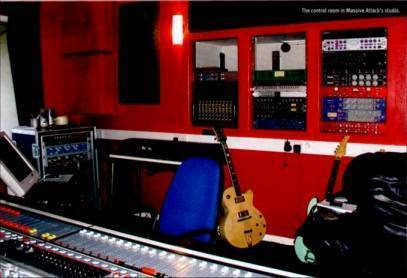

The main racks in Christchurch Studio, including (right to left,

from top): Avalon 737 voice channel, EQ, SPL Transient Designer, Empirical Labs

Distressor compressor (xz), Focusrite Red 7, ISA 215 and 430 voice channels.

Red 2 EQ; Joemeek SC2.2 compressor, Drawmer 1960 compressor, Focusrite Compounder

compressor, Tube-tech LCA 2B compressor; rackmounted desk EQs.

Loop And Jam

100th Window

has been three years in the making, mainly because of the band's initial approach

to the recording process. Off the back of touring Mezzanine the live band decamped

to Ridge Farm Studio, where three Pro Tools rigs'were set up to record their

every move as they jammed around pre-prepared loops. "We had one multitrack

Pro Tools rig recording everything and one playing the loops," explains

Lee Shephard, the band's engineer and Neil's right-hand man. "We then had

another machine just recording the stereo out of the desk, so that we had a

constant monitor mix of what we were hearing to reference. I had to keep doing

drive changes, running down to the machine room to swap a drive and then back

up."

"As a technical

exercise it was quite an achievement," continues Neil. "We spent a

month doing that, recording every single note that was played, because we wouldn't

actually play the band anything before they started recording. We ended up with

about 80 hours worth of material to sift through and to piece together as an

album. It worked really well on the basis that we got some great performances,

but sadly, when you took things out of context they suddenly didn't work."

As a concentrated

effort the band had spent around six months working like this before realising

it was not going in the right direction, even though at that stage they weren't

sure what the right direction was! Only one part was eventually used from those

sessions, a guitar riff by Angelo which can be heard on 'What Your Soul Sings'.

Back at the band's Bristol studio they made the difficult decision to go back

to basics. "We literally scrapped the whole lot and started again,"

confesses Neil. "And we started in more of a way that we'd been familiar

with, where you would start with a sound, and that sound would become a part,

and that part would become a loop or small musical arrangement, and then you'd

start building over the top of that. Again, because me and D both see music

as a very visual thing, the textures have to be there — we have to have

those contrasts, whether we start with a small synth part and then put some

crusty guitars against that, or start with some beats and create a picture from

that.

"We needed to

start from that very simple basis, sketching out an idea and then filling it

in. It had to be a building-block kind of process-for us to actually feel that

it was what we wanted to try and do, otherwise it was too out of control. We

could appreciate the music that the band were making, it was very exciting,

but you couldn't take one single part and say that was the core of it —

it just didn't hang together. The bass line might work well with the drums,

but you'd take the bass line on its own and it didn't sound that great. So it

was only when we wrote a bass line that we wanted to hear on the record that

we started to get to the core of what we were trying to do on this new album.

"I guess it's

always been an abstract process with Massive Attack. There's never been logic

to it, it's always been a gut thing — I don't approach things from a cerebral

point of view — it's always whether something does it for me or it doesn't.

And wherever I am dictates where I'm going."

The band's Wurlitzer electric piano, and rack containing (from

top) Zoom 1201 effects, TC M3ooo reverb, Electrix Mo FX effects and Filter Factory,

Yamaha SPX90 and SPXiooo effects, Alesis Midiverb effects, SPL compressor, Drawmer

DS201 dual gate (x2).

Free Form

This intuitive

and cavalier approach helps give the tracks on 100th Window a real sense of

natural movement untouched by formulaic or standard structures. "There

are structures in the tracks, but it's always what comes before that dictates

what comes after," explains Neil. "I think people, especially these

days, get four bars, build that up and find another four bars to go with it

— then one's your verse and one's your chorus — and I don't find

that particularly inspiring. I like things to grow, in the same way that in

a conversation you'll start at one point but you'll end up somewhere completely

different, and it will be

a surprise and exciting because who could have predicted that you would have

ended up there? In the same way I think that music has to have an element of

surprise, there has to be a sense of natural progression even if you suddenly

drop a huge drum beat over a nice synth part. It has to seem like that was the

right move to make, but you can't get there before you've done the nice little

quiet bit. It has to make sense as a journey. Too much music these days doesn't

pay attention to what music should be about, which is communicating ideas and

feelings. If you get that bit right then you can write unconventional structures

and melodies that work."

The free-form nature

of the new tracks is also a direct result of the band fully embracing Pro Tools

as a writing medium and abandoning sequencers, samplers and MIDI. "On the

last album we used Cubase Audio and

the Akai MPC3000, but these days samplers and MIDI are hardly ever used. I think

the fact that we haven't used MIDI or samplers has affected the sound of the

album," admits Neil, citing the strings on "What Your Soul Sings'

as an example. "That started when we brought in a violinist friend of ours,

Stuart Cordon, and he played just a simple three-note two-chord thing. I used

Pure. Pitch to rearrange the notation and create the arrangement, rather than

get a sample CD of string notes and then use MIDI. It's only through the context

of Pro Tools that I can fully realise things like that and it's an essential

part of the way I work these days."

To The Edge

Neil has a passion for making

things sound like anything but what they are, like the weird and randomly fluctuating

keyboard sound on 'Small Time Shot Away'. "The reality of that is that

it was just a single chord held on aJuno playing a sine wave doing an arpeggio,

but I actually went through using Wave Mechanics' Speed plug-in to create different

textures. It was just a one-bar loop but I love it when you take something,

slow it down, take it up or down an octave and just keep pushing it until obviously

it's unusable as sound — but always going right to the very edge before

you come back and say 'Well, I'm going to use that bit.' So the keyboards on

that track were created through that process and then re-editing all those parts

to work as a performance.

"If you're making

music and you know what's going to happen next then it just becomes boring.

I love the part of it where you try something, you don't know what it's going

to sound like, press go and it either sounds a complete mess or it sounds amazing

— and that's the bit I get offon. If you're surprised by what you're doing

then people listening to it will be even more surprised."

There are also some

intriguiging effects on the intro to another track, 'Butterfly Caught': "That

was from one of those all-night sessions that I did! I think they were originally

some cymbal sounds, and again, I stretched them until they became something

completely different and the harmonics within the sounds themselves became the

more dominant features. Then I took those harmonics and created the notation

using Speed to alter it beyond all recognition."

Similarly, there's

a bass line on 'Butterfly Caught' that was originally a vocal part by D: now

it sounds more like a Moog bass. "We pitched it around, put it through

Recti-Fi and various other plug-ins to create that texture, and then edited

that to create the bass line. With the amount of processing available nowadays,

especially on Pro Tools, if you wanted to you could make a complete orchestration

from a cymbal sound. You can warp sounds until they become something completely

different. A percussive sound becomes a melodic instrument, for example the

drums on 'Everywhen' — that was just a kick, rim shot and a hi-hat but

put through various delays, Doppler effects and CRM pole filters that basically

created a melodic backbone for the track. A lot of people think it's guitar

noises but there's not a single guitar sound on that track.

"I like turning

sounds on their head — it's a challenge and by setting yourself that challenge

you're using your ingenuity, something that's very personal to you, based on

your experiences, your view of the world, so it becomes unique,"

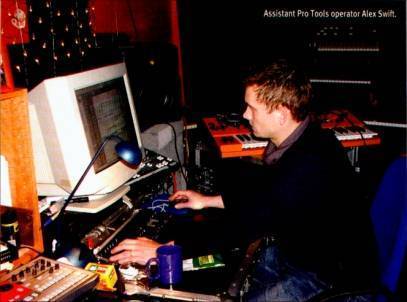

The machine room houses the G4 Mac and the power supply for the

band's DDA desk, as well as its Optifile automation system.

Mixing

100th Window

was mixed, in the traditional way, at Olympic Studios with the aid of Mark 'Spike'

Stent. His job was to enhance the tracks and give them the right perspective,

because much of the material had in effect been mixed already as part of the

recording process.

"A lot of the

sounds were committed, edited, re-committed and then edited again, so you'd

almost have to use what we'd done here, although we always gave ourselves the

option to go back if we needed to," recounts Neil. "For the last three

years we've been backing up everything we record, and we've now gone past the

Terabyte [1,000 Gigabytes] mark on our backups."

"Often we'd work

with bounced material," adds Shephard, "and when we wanted to change

things we would follow the trail back to when it was originally mixed, find

the Pro Tools Session and get that up. I use Retrospect, a Mac-based program

that does incremental backups, and it's got a comprehensive search facility

so that you can search for things using keywords and dates. Often I have to

find things that were done two or three years ago, maybe something that was

done for another track that they want to put in the latest track. So I have

to hunt it down using all the clues available."

Mixing To Stems

For Neil

Davidge the arranging and mixing process never stops, it's an ongoing thing

that is taken right up to the last moment — even when mastering. "We

mix down on to 192 and the stems will comprise of a stereo drum track, stereo

bass track, stereo vocals, stereo guitars, keyboards and strings — so

we'd probably end up with four or five stereo tracks which would comprise the

mix. We did a fair deal of re-EQ'ing at the final cut [utilising their new newly

acquired Sony Oxford EQ plug-in] to the point where I

was arguing with Tim, the cutting engineer at Metropolis, that perhaps he should

get some kind of mixing credit on the album!

"The way we did it was to do the basic stem tweaks here in Bristol, mainly

rides and a bit of rearranging, and then we'd go to Metropolis and EQ and fine-tune

some of the rides at the cut. I think that's going to happen more often —

a lot more people are going to be going in and cutting from stems. We did it

on Mezzanine, although at that point it was a lot more basic. As a basic system

for cutting from it makes a lot of sense — the only benefit you don't

have is the overall compression that you might have at the mix, but you can

always hire in an outboard compressor for that.

"We spent three days cutting this album. The first day we went in listened

through to everything and did some overall tweaks on the EQ, then the next day

we started tweaking individual things because we'd find that by EQ'ing the whole

track the vocals would get lost and we'd need to EQ other parts to compensate

for that."

Neil has definite ideas about how stereo should be used to create a compelling

mix, and uses a lot of movement and phasing effects. "It creates a wider

picture," he explains. "I guess it's from a point of view of trying

to create a picture, again, that's interesting — so you obviously want

movement in it. It turns your speaker system into less of a window and more

of a theatre for the sounds, and the music wraps around you as you listen to

it. I've never liked records where you feel like you have to put your head between

the speakers to get the full benefit — I like records that come out from

the speakers to greet you in the room. Then the room is more of the environment,

which is much more engaging from that point of view."

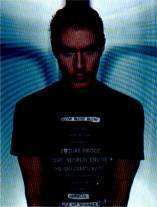

Robert Del Naja, aka D, is currently the mainstay of Massive

Attack.

Theatre Of Sounds

100th Window, the title taken from a cult electronic security book

written by Charles Jennings, is an intense and multi-layered album. One of the

band's self-imposed briefs was to create an album that was warmer than Mezzanine

but not softer.

"We tend to set ourselves these impossible tasks: 'bigger but smaller',

"warmer but not softer'," laughs Neil, "and we talk about it

and get excited about the concept, but there's always the practical aspect of

how you can physically make it work. I'm pretty nocturnal when it comes to making

music, I work through the night a lot of the time, and it's then that these

conflicting ideas come together and actually make sense, but it's not easy.

It's a bit of a tall order to make an album that's good and different. Especially

these days it's almost an impossible task because nothing is completely original

any more — it's just not feasible. So you've got to go to other places

and set yourself almost impossible briefs to get somewhere different, which

is what we definitely did with this album. We challenged ourselves in many different

ways.

"This album's not going to be an album that you listen to once and go 'Wow,

I totally get this.' It's going to have to be an album that you listen to half-a-dozen

times before it starts to make sense. Most of my favourite albums, and the ones

that I continually go back to, are the ones that took me a while to get into

in the first place. After we've . finished an album I can't tell if it's genius

or just OK — I won't be able to tell you that for maybe another six months.

You just try and put all your positive energy into it whilst you're making it

and hope that it represents what you were going through at that point. And it

does represent where we were at creatively through the making of the album."

The Red Light's Always On

Massive Attack albums are renowned for their carefully chosen guest

vocalists — these have included Shara Nelson, Tracey Thorn, Tricky and

Liz Frasier, and now on 100th Window the band have finally got to work with

SInead O'Connor.

"I think it was on Protection that the band first considered Sinead as

an option," recalls Nell, "so it's always been in the back of everyone's

mind that at some point Sinead might be a good person to collaborate with. We

originally tried Liz [Frasier, of the Cocteau Twins] and it just didn't work

out because she wasn't in the right place to be writing again — she's

got some conflict at the moment as to whether she should be writing or performing

— which is a real shame because one of the highlights of my musical career

was sitting in a room recording her, especially on 'Teardrop', it was really

quite a moment. So I was disappointed and tried to encourage her Into the studio

for the best part of a year and I got her in a few times and we got some things

down, but she just didn't have whatever it is in her to go to the next stage.

So In the end we had to call it a day and started panicking about who was going

to sing on this album.

"Sinead's a very different singer to Liz. Liz is quite a perfectionist

when she sings — we'd be looping round a section and I'd hear her working

out the timing of her vibrato on single words! Sinead's a totally different

kind of performer — it's more about the emotional context and the lyrical

aspect of It a'nd If you've got her In the right frame of mind then that's the

take. It might have a few wobbly bits in it but that's her personality. She's

a very outspoken but nice person to work with."

Massive Attack's studio space at Christchurch has no live or vocal room: instead,

everything is recorded in the control room, an aspect that Neil uses to his

advantage. "I like working with vocalists In the control room. There's

a certain communication that you need to have, not necessarily a verbal one,

but to see what they're doing and how you can help them. From a production point

of view I prefer singers to sit down, to be relaxed, even though there may be

certain problems that you get with breathing. It seems to suit the Massive Attack

sound to have them sat down In a very relaxed scenario to perform, because you

get a presence and a conversational kind of thing. I love that in great singers,

you listen to the record and you feel that they're talking to you, singing to

you — I don't like It when you've got a voice at the back of the mix drowned

in reverb, it doesn't do anything for me.

"I like to capture the moment in the studio and tend to record everything

that someone does, ending up with hours of material of which you'll only pick

out 30 seconds — but I prefer to work that way rather than say 'That was

a great part, practise that and then we'll go and record it.' The moment's lost

as far as I'm concerned — it happens once and that's it. We've got a scenario

set up in the studio where we can record everything that's going on, with large

removable drives we can just keep going for hours. And that for me Is most Important:

there's magic that happens in the studio. It might be purely accidental, but

if you're recording as those accidents are happening then those accidents can

become the track. Usually people only start recording when they've decided what

they're going to do, which for me is a definite no-no. There's also a certain

confidence that a performer has whilst they're rehearsing a part, which is lost

when they know the red light's on — so to get over that phobia, the red

light's on all the time. As soon as you walk In the room. the red light's on,

so you get used to It and It's the norm."

The Vocal Path

Lee Shephard's working relationship with the band often requires him

to take sounds created by Neil and make them work within the context of a mix,

a process that will quite often Include reprocessing, EQ and compression. There's

also a particular routing when it comes round to recording vocals.

"It begins with a Neumann M147 valve mic which goes straight into the Avalon.

I don't use any compression or EQ at that stage, Just use it as a preamp. Then

it goes from there into the Drawmer 1960, on which I really like the compressor

at the number 6 setting. I used to use the Focusrlte, but the things evolved

during the making of the album and I settled on that chain, which has a lot

to do with the compressor on the Drawmer. Then the signal goes out of that straight

Into the Apogee Trak 2 and that's It. We don't tend to put any EQ on, just keep

a consistent sound and EQ In Pro Tools if we need to."

The chain is something that Lee's developed over the last three years and works

well with most voices including D's, which has a particular rasplness and airy

quality. "I will double-track certain things but a lot of that is inherent

in his voice," says Neil. "It depends on when you get him— if

you get him after the pub, and we tend to record most of his vocals late at

night, he's probably been talking all day and his voice has got to the stage

where it is quite raspy anyway. I'll normally record half-a-dozen takes with

him, comp together from those and find a take that represents his vocal sound

the best. He's always got something to say, lines in his head that come out

there and then. If you'd sat him down with a paper and pen he wouldn't have

written it in that form."

Record First, Write

Later

As mentioned earlier, Neil Davidge is very much a producer who will

'record first and ask questions later', and this means he often ends up recording

vocals before the song In question is fully written. "I have a way of working

with artists, although SInead O'Connor didn't fit into that category, where

I like to get people to sing a song the way it feels right at that point, and

it doesn't necessarily depend on them having the structure of the song worked

out. If the mood is right and they're in the right frame of mind I'm quite happy

to get the vocal down, in the same way as with guitars or any other sort of

instrumental performance. And generally that tends to be at the time when they're

writing the thing Itself and so I like them to finish off the writing process

whilst we're recording, because that's the point at which the magic occurs.

"But obviously the down side of that Is that sometimes the structures aren't

wholly thought out, so it may require that I go In there and re-edit the performance

to work as a song. Equally there are times when melodically it might not make

sense because the structure's not there and you don't know if you're going to

go up on the last line or keep It down. So from time to time I will change a

melody to make it work as a song structure, and I quite often use Pure Pitch

to do that, which I tend to use more as a writing tool than a pitch-correction

tool. I think a lot of people slap Auto-Tune over the whole performance and

that's it — I don't like to do that and I don't like it to sound like

you've severely pitched someone."

One instance where Neil took this method to the limit was when working with

long-time vocal contributor Horace Andy. "We had a simple melodic structure,

D would write the lyrics and then I'd get Horace to sing round the one line

constantly going round and round, recording different ways of singing that line.

Then I constructed the song afterwards, choosing the lines that worked best

and that seemed to flow naturally, which was a very abstract way of JH working.

I'd always get him to start quietly and —w then build to a crescendo and

the come back down again. I'd usually use the line after he'd sung in full voice,

once he'd settled back down and after he'd got the classic, trademark gated/tremolo

vocal effect out of the way."

Luckily Horace didn't object to this way of | working. "When we were doing

it he was very | suspicious, and it took a lot of coaxing to get Mm to do that,

but once we'd done it and after I'd comped the tracks and rearranged the vocals

then played it to him, it blew him away. I guess it takes a lot of trust for

a performer to let someone do that, but I used to be a singer so I come at it

from that angle."

Massive Attack's

Gear

Computer

system

• Apple Macintosh

G4 800MHz with a 13-slot Magma PCI expansion chassis.

• Apogee Trak

2 recording interface.

• Digidesign

Pro Tools TDM system with 888/24 and three 882/20 interfaces.

Plug-ins

• GRM Tools.

• Sony Oxford

EQ with GML option.

• Waves Platinum

Bundle.

• Bomb Factory

Compressors and Voce Spin.

• Focusrite

d2 and d3.

• Audio Ease

Altlverb.

• Line 6 Echo

Farm and Amp Farm.

• Wave Mechanics

Ultra Tools 2.0.

Outboard

• Al Smart C2

compressor.

• Avalon 737

voice channel.

• Drawmer 1960

compressor.

• Focusrite

ISA 430 and ISA 215 voice channels.

• Focusrite

Red 2 EQ and Red 7 voice channel.

• Focusrite

Compounder compressor.

• Tube-tech

LCA 2B compressor.

• Calrec PQ1785

EQs.

• Neve 33135

EQs.

• Joemeek SC2.2

compressor.

• Empirical

Labs DIstressor compressor.

• SPL Transient

Designer dynamics processor.

• TC Electronic

M3000 reverb.

• Electrix Filter

Factory filter and Mo FX effects.

MIcs

• Neumann M147 Tube and U87.

• Shure SM57.

• Coles 4038 ribbon rnlc.

• AKG C391 and C414.

Monitors

• Genelec 1032A.

• Yamaha NS10M.

http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/Apr03/articles/massiveattck.asp