Massive? We still could be (The Times,

25th March 2006)

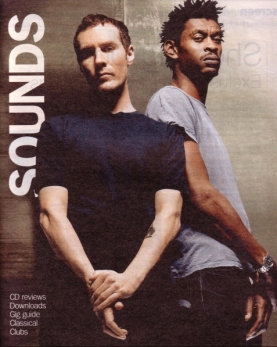

Massive Attack are set to assault the charts again with a greatest hits compilation and a new studio album. Mike Pattenden went to meet them — separately.

It is totally against all protocol,” says Robert Del Naja, aka 3D. Massive Attack’s frontman shakes his head in disbelief at my request to hear some of his work-in-progress.

“No one has heard anything outside this studio,” confirms the producer, Neil Davidge, who is sitting at the mixing desk in their studios just south of Bristol. “Not even G.”

Grant Marshall, aka G, is the only other remaining founder member of Massive Attack. And though he, too, is laying down some tracks for their first album in eight years, the studio that he is working in is miles away on the other side of Bristol. As the day wears on, it will become increasingly clear that the distance is metaphorical as well as literal.

G played me a track this morning, I say, trying not to sound too manipulative. “Yeah?” says 3D, eyebrows raised. “Was it any good?”

I tell him that it was lovely — an aching groove entitled What I Am, featuring a new local singer called Yolanda, who possesses one of those bruised, smoky voices the band have a habit of unearthing.

“You see how much I know,” shrugs Del Naja. “But that’s the way it has to be these days.” I apologise, embarrassed for opening a can of worms. “Don’t worry,” he smiles. “G hasn’t heard any of our stuff either. It just reinforces the unconventional nature of this band. It goes back to the early days. We were all such diverse personalities, that’s what made the music different.”

It certainly was. And though Del Naja and Marshall remain commendably focused on their future sound, a greatest hits compilation out this week provides an opportunity to review Massive Attack’s long history.

That morning I had met Marshall in a small studio on College Green, opposite Bristol Cathedral. Marshall looks a decade younger than his 47 years, dressed in jeans and an old Wild Bunch T-shirt — Wild Bunch being the Bristol hip-hop collective that he founded 20 years ago with Nellee Hooper.

“Our initial efforts were a joke,” he recalls in his soft West Country tone. “You’d have thought that Bristol was part of America back then, the way we rapped. We realised that we were fooling ourselves so we decided to make it more colloquial, to reinterpret the sound from our perspective. Then the other influences crept in, the reggae and the punk.”

The metamorphosis into Massive Attack began with The Look of Love in 1986. Five years later the band, by now based around Del Naja, Marshall, the rapper Tricky and Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles, was ready to release one of the most influential albums of the 1990s. The slo-mo beats, lush orchestration and deep, soulful singing of Blue Lines created a landmark in the evolution of British dance music, launching the so-called Bristol sound of trip-hop and a host of imitators.

“I suppose it was flattering, but ‘trip-hop’ is no more than a convenient label,” says Marshall. “I wish they would call it Massive Attack music, but where would you file all the others? I read a piece not long ago in which Morcheeba were slagging us off. I thought, ‘Hang on, without us . . .’ ”

Blue Lines was followed in 1994 by Protection, which magnified the lushness, and then, four years later, by Mezzanine, which turned up the moodiness. But by then cracks in the line-up had become fissures. The irascible Tricky went solo after Protection and Mushroom moved to New York after Mezzanine.

“The way we work makes us a nightmare for a record company,” Marshall admits. “I can imagine the conversations down the years: ‘Where’s the money in this band?’ Well, there is no money in this band. We’re a loss leader.

“One of the reasons that we decided to put the ‘best of’ out before the new album was to give the label something back. Most bands put out a compilation after ten years, but we have only managed four albums in 15 years,” he cackles.

The fourth and most contentious was 100th Window, released in 2003. It was made by Del Naja with Davidge after Marshall took a parenting sabbatical (he now has two children, with a third on the way). The album, a tense, brooding affair full of throbbing beats and dense guitars, topped the charts but took a critical pasting.

“I stood back, but it wasn’t really the sort of sound I’d have gone for,” huffs Marshall. “I understand it had to move on, but I was still DJing then and people would come up and say: ‘When are you gonna be back to put some soul into it?’ It didn’t have any black sounds at all. I felt I’d let the fans down.”

Surely leaving Del Naja to make the album alone means that he has to shoulder some blame? “Absolutely. That’s exactly why I’m back. I’m here to readdress that. I’m not taking it away from D because we gained some new fans, but . . .”

G sounds confused as to his motives. Did he want to become a house husband or avoid conflict? In short, did he cop out? “It was a failure but a failure on my behalf,” he nods. “To let myself be driven out by him because he can be a control freak. I didn’t have the strength of character to stand up to him then.”

Do they even socialise together? “Nah,” he says with a laugh. “To be honest, I don’t think we even like each other.”

These words must be taken with a pinch of salt. He and Del Naja are still partners in Nocturne, an exclusive bar just around the corner from Marshall’s studio, and toured the world together three years ago.

“One of the reasons I came back was the charges levelled against D,” admits Marshall, suggesting that they are not as antipathetic as they make out. “I really felt for him. They were going out on the road and it was looking like it might not happen. He was in a state but we soldiered on and it was a resounding success in the end.”

The charges in question were that Del Naja had been downloading child pornography. A month after his arrest early in 2003, the police dropped the investigation for lack of evidence but not before his name had been leaked to the tabloid press.

“My Kafka moment,” nods Del Naja when I bring the subject up. It is ironic, he points out, that 100th Window’s title was inspired by a term for holes in a computer’s security.

“Fortunately, everyone I knew was great,” says Del Naja. “People like G rallied round but it was horrendous for a while. I’m still bitter that my name was dragged through the mud.”

The mood of 100th Window is full of foreboding, but that can be traced to the atmosphere in which it was conceived rather than any prescience of personal doom. “I’m naturally quite a dark character inside and it was a dark time: post September 11 and the Iraq War,” Del Naja recalls. “It was symptomatic of the isolation, of having to do it alone. It was painful but everyone was demanding a Massive Attack record. I’m pleased by the way it turned out but I couldn’t make a record like that again.”

I repeat Marshall’s comment that it’s not the sort of record that he would have made, either. “But everyone’s still waiting for the sort of record G would make, aren’t they?” says Del Naja with a thin smile. “You are defined by the work you do, not the work you don’t do.”

What about the suggestion that he had lost the soul, the blackness? “Look, there’s a lot of misconceptions about my role and this band. Take the new single that we put on the compilation. Everyone said: ‘Oh, you can tell G’s back, it has the trademark Massive sound’.”

Live With Me, made with the folk-soul singer Terry Callier, does indeed display all the classic touches of Massive Attack’s finest moments. “Well, G didn’t have anything to do with it, it was me and Neil. The way we work now, me here and G over there, just suits us. We’ll put it all together soon and see how it fits. We’ve even discussed making it an album of two parts, like OutKast’s Speakerboxx/The Love Below.”

Due for release early next year and with a working title of Weather Under- ground (a name inspired by the radical 1960s movement), the new album seems likely to be Massive’s most diverse yet, with both Del Naja and Davidge back on board after a visit to New York where they collaborated with such hip names as TV on the Radio and the Dragons of Zynth.

Earlier that day I asked Marshall whether, if the roles had been reversed and Del Naja had taken a break in 1998, Massive Attack would still exist. “No, probably not,” he conceded. “He has a drive about him. D takes care of all the details — I’m not so focused in that sense.”

“It’s true,” agrees Del Naja. “I think if I hadn’t made the effort there would only have been a couple of Massive Attack albums. Part of me says I can’t be tethered to this concept all my life; the responsibility is too great. The other part of me says that Massive is what I do. I don’t have any family and the band is part of the reason for that. The issue came up with a girlfriend ten years ago when we were just about to start touring properly and I opted to go on the road. It’s never come up again.”

The interview concluded, I repeat my request to hear some new material. After much thought, Del Naja relents. Davidge clicks on a track marked Tunde01. The sound that emanates from the giant studio speakers can best be described as Joy Division covering an old Ray Charles record: a raw R&B vocal with juddering basslines and rolling piano.

“It’s mental, isn’t it?” says Del Naja when it ends. “We’re throwing some mad shapes together, but that’s the way it has to be if we’re going to progress. Massive Attack has always been about evolution. It’s not about me or G or anyone else.”

Massive Attack: their albums and collaborators

Blue Lines (released April 1991; highest chart position 13)

Grant “G” Marshall: “We made it round at Neneh Cherry’s house. It was Neneh that hooked us up with Horace Andy, the bad-ass Jamaican with the voice of an angel.”

Robert Del Naja: “I nicked the idea for the imagery from Stiff Little Fingers’ Inflammable Material. The sound was defined by the tracks with Shara Nelson. We didn’t give her a great deal to work with, then we took most of that away.”

Protection (released October 1994; chart position 4)

G: “Tracey Thorn sang the title track. I worked in a record shop in the mid-1980s and Everything But the Girl’s albums used to fly out the door.”

D: “Tracey is a great songwriter. We finished another track that has never seen the light of day. I think that it was too personal.”

Mezzanine (released May 1998; chart position 1)

G: “We worked with more musicians rather than sample everything. Elizabeth Fraser was top of our wanted list for a long, long time. And she’ll be back.”

D: “Bono told me that he was talking music with Al Gore and Gore was saying: ‘Which one, Bono: Blue Lines or Mezzanine?’ He’s right. I think Mezzanine is as strong as Blue Lines.”

100th Window (released February 2003; chart position 1)

G: “It was like the nursery rhyme. They all rolled over and only one was left.”

D: “We met Sinéad O’Connor around the time of Blue Lines but it took years to hook up. She believes in justice, right and wrong. Totally unambiguous.”